I thought I was doing some good in Honduras – offering free cataract surgery on my own dime, importing equipment, making a difference. But about five years in, a 37-year-old patient walked into my clinic with posterior subcapsular cataracts. And this conversation followed: “Yes, we’ll do your surgery.” “I’ve been reading on the Internet. Are you going to be doing phaco?” “No, we’re not going to do phaco.” “I read that’s the best way of doing it, why aren’t you doing it the best way?” “I don’t have phaco here – but if I could, I would.” “I’m going to think about how badly I need this surgery...” Even back in the year 2000, the patients who received charity care in Central America were, thanks to the Internet, quite savvy – and they wanted the best. I realized that I’d either have to quit – or give them the best. And that’s when I started importing more sophisticated equipment and working with local doctors to start building an infrastructure to provide a better service. The process taught me an awful lot, and I’ve gone from being a medical tourist, albeit on the provider side (I’d go down for about a week, do a bit of surgery, feel good about myself, then go home), to something more than that.

Lesson #1: Ask nicely

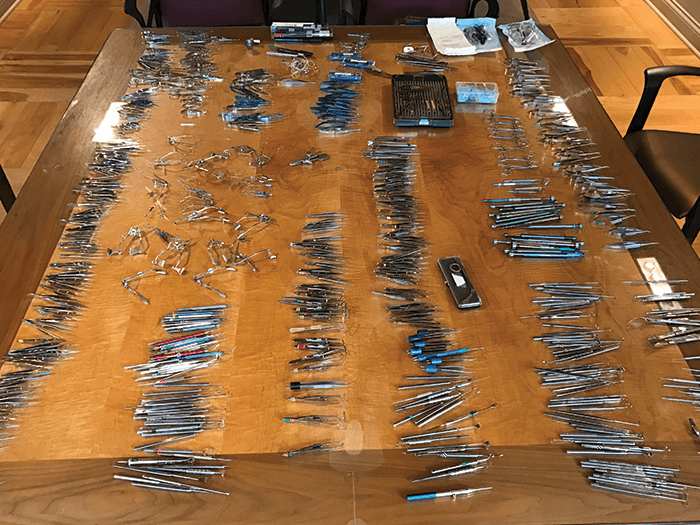

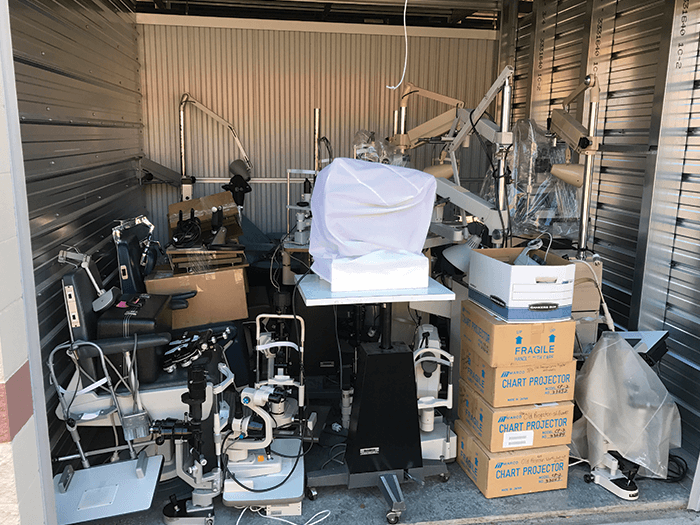

There’s a difference between asking nicely and doing so in a productive way, and begging and being a jerk – they are at very different ends of the spectrum. If you ask somebody nicely and with a pure heart, more often than not, they will say yes. Once I’d learned that, I was amazed by the number of people who came out and worked with us. For example, I work with one of the best phaco machine repairers in the world. He’s based in the US and works for Johnson & Johnson Vision. He volunteers his time and expertise to support our efforts in Honduras in his free time – tuning up the equipment before we send it down, and then he comes out to Honduras to set it all up. In Honduras, we have two biomedical engineers who are part of another organization that we made friends with. We’ve already trained one of those engineers in the US, which is all part of building up that essential infrastructure. And it all started by asking for help nicely.Lesson #2: Respect that people need to make a living

Don’t spend all of your money on supplies and transportation – some local people who want to help still have to feed their families; consider salaries. Equipment manufacturers also want to help, but importing equipment and giving it away for free while totally ignoring the local situation can have a negative impact on their local partners. If something is likely to affect a local distributor’s business, talk to them about it. Some charities ignore the local reality in the ground; they burst onto the scene as a totally self-contained unit, perform lots of cataract procedures, then fly back home – and ruin local people’s livelihoods in the process. Remember that a single donation can completely change the market, and it can take years for the local system to recover. If, however, you involve everyone in the process, the local distributors can get involved in helping the very people who need it most.It’s not that we won’t import a vital piece of equipment because of the impact on their business – but we can mitigate the impact in the process. For instance, I imported an expensive photo slit lamp from the US that I couldn’t get locally. But before I did that, I bartered with the local distributors. I said, “Look guys: I can’t get this locally, so I want to import it – will you repair it once it’s here? If you do, I’ll buy this other equipment from you.” Here, we both get something out of the process. Respecting partners goes a long way to achieving your goals.

Lesson #3: Respect your patients, their time, and the danger they put themselves through to reach you

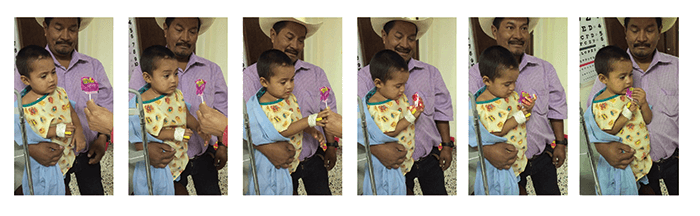

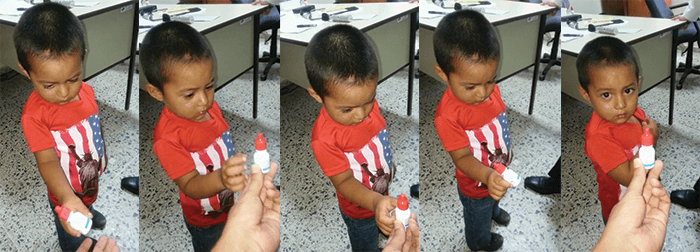

I get up at about 3.30 am in Indianapolis, board a plane, travel by car from the airport, and arrive at the clinic at about 4.00 pm local time. It takes a while! But it can take even longer for some patients to get from their house to the clinic – and involve greater levels of danger. My patients are blind; they can perhaps tell the difference between light and dark, but that’s it. So even though the surgery is free, they still have a journey to make; possibly needing to hold someone’s hand while they walk to the local bus stop, taking one or two buses (at not insignificant cost) to get to my clinic in Honduras. Then it’s another hour’s walk up a very steep hill to get to my clinic from the bus stop. Suddenly, my journey doesn’t seem too bad – and I don’t have to worry about tripping up or walking into traffic.Yester, a four-year-old boy, had been blinded by cataract for the last two years. He was in particular danger because his family lived on a very steep hillside; to keep him indoors – and safe, they kept him in chains. The local hospitals didn’t have the capabilities to perform pediatric cataract surgery – and that’s where I stepped in. The local hospital agreed to pick him and his family up and also to provide the operating room. I agreed to provide the equipment and the expertise. I performed the surgery and implanted a Tecnis multifocal lens, to help him see at both distance and near – it was not realistic to expect Yester would be able to obtain glasses postop.

Two months later: Can he see perfectly? No. But he can interact with his world – and that means he can have a life.

Lesson #4: Your intervention changes the fabric of society

I got really excited about working in Central America when I realized that restoring the vision of grandparents actually changed the social fabric of the family. In the US and other developed countries, middle-aged people are somewhat oppressed – they’ve often got kids and aging parents to juggle. But that’s nothing when compared with a Central American family that has to cope with blind grandparents. When I operate on a grandmother, she contributes to the family again. The mom is suddenly free to look after – and read with – the kids. The upshot is that the next generation has a better chance in life. It reminds me of a TED talk by a very interesting Swedish epidemiologist, Hans Rosling, who noted that the fundamental event that changed society in Sweden was the washing machine. Suddenly, grandma didn’t have to spend all of her time doing the wash; she could help do the dishes, she could help cook – and Mom could read with the kids. He recognized how much better off the next generation was after the washing machine was introduced.In a small way, I think we’re helping to do the same in Central America.

Lesson #5: Bad clinics can get closed... by drug dealers Hugo Chávez was famous for using Venezuela’s oil wealth to fund doctors for the poor – he would send tens of thousands of barrels of oil to Cuba each day. Part of what he got in return was tens of thousands of Cuban doctors and teachers who worked in its barrio slums. Things are different now – oil prices have dropped – but, at the time, the Honduran government did the same as Chávez. The problem was that when it came to cataract surgery, many Cuban doctors did a bad job – and people simply wouldn’t go back and risk having their second eye operated on by them. I know this story well because I ended up doing many of the second eye surgeries myself... Being a part of this world exposed me to one leveling effect of the drug trade. The barrios where the Cuban doctors worked are areas where drug dealing is rife. Quite naturally, the parents of drug dealers get cataracts. They go to the local Cuban-run clinics, it doesn’t go well, and their parents are blinded. The drug dealers know how to deal with that... And the clinics close. It’s an unusual case of where drug dealing was actually beneficial to society! The US government has been in a constant struggle with Venezuela under Chávez and his successors for many years – and competing philosophies on how to help those in need is one of those areas of conflict. It is ironic that US volunteers were providing a very strong counterpoint to the efforts of the Venezuelan government by providing a superior service to the needy people of Honduras.

Lesson #6: Interventions on a small scale can be more effective than big ones

Every healthcare system has its problems – Central America is by no means unique in that respect. But they also get many aspects right. The systems in Central America are shockingly efficient – they have to be because they have so few resources to work with. If you feed them resources in the right way, they are incredibly effective at using them. Consider Mississippi – it is the poorest state in the US by far with a median household income under $40,000. In Honduras, which shares a coast on the Gulf and has a similar population, the median income is under $4,000. So on a tenth of the income, they take pretty good care of themselves.When it comes to charitable donation, I’ve observed something important: it’s bad to give large injections of cash; large amounts of money end up just disappearing. But small boluses of money – properly managed – can be incredibly powerful at helping people. I’m finding that the local doctors are really great at spending that money effectively and efficiently in the local supply system. As noted above, they are used to be being careful with their cash.