The human eye is an impressive construct, designed to constantly protect and lubricate itself by secreting tears. But there are some animals whose eyes have to protect themselves against far more difficult conditions: marine mammals, who spend most of all of their time in the harsh ocean water. The seas have hosted marine mammals for nearly 50 million years (1) – and in that time, appears that those mammals have evolved unique mechanisms to cope with their environment: an impressively antimicrobial tear film. Recently, researchers from Schepens Eye Institute and Massachusetts Eye and Ear (Boston) examined the tear film and saliva of bottlenose dolphins, rough-toothed dolphins and manatees to see whether those substances have antimicrobial activity (2).

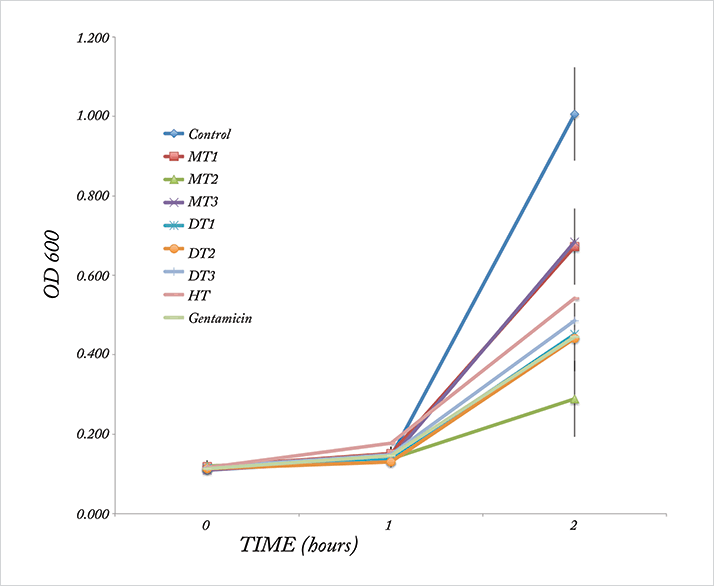

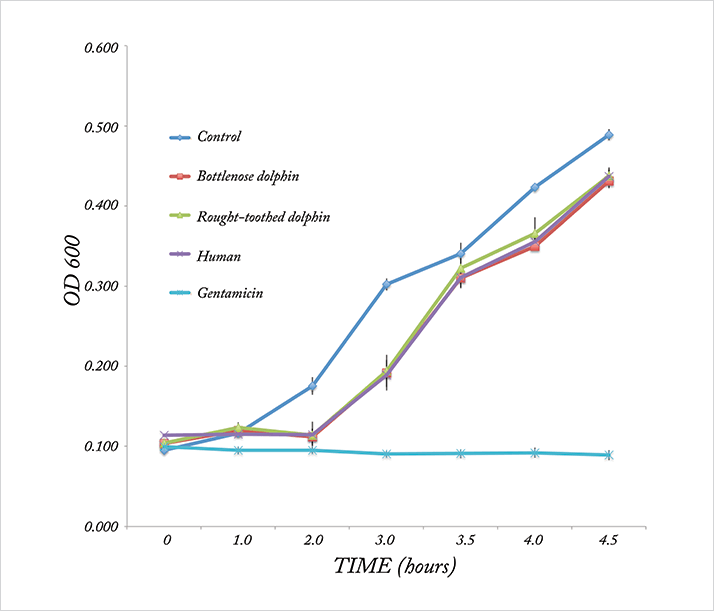

To check for antimicrobial effects, dolphin, manatee and human tear samples were incubated with strains of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The researchers found that in as little as two hours, all three tear types showed significant inhibition of E. coli growth (see Figures 1 and 2). Though the tears had little effect on the slower-growing P. aeruginosa, other tests using dolphin saliva showed that it was able to inhibit growth of the bacterium at 4, 4.5 and 22.5 hours of incubation. The results of the early study indicate an antimicrobial effect of marine mammal tears, but there’s a lot more work to do. Next, the scientists have to analyze the composition of the secretions and ascertain which factors are responsible for this activity so that they can be isolated and studied further. A new kind of antibiotic may be hidden beneath the surface of the ocean – but if so, this is only the beginning of the dive into its secrets.

References

- MD Uhen, “Evolution of marine mammals: back to the sea after 300 million years”, Anat Rec (Hoboken), 290, 514–522 (2007). PMID: 17516441. R Kelleher Davis, P Argüeso, “Antimicrobial activity detected in ocular and salivary secretions from marine mammals”. IOVS, 56, ARVO E-Abstract 4163 (2015).