Gwyn Samuel Williams, medical retina fellow at Moorfields Eye Hospital, presents the global challenge of diabetic macular edema that is facing ophthalmologists; Disease processes

Educational content provided by Alimera Sciences.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is the commonest cause of blindness among the working population and prevalence is skyrocketing, not just among those living in the West, but throughout the world. Diabetes currently affects 200 million people worldwide, a figure set to almost double to a staggering 360 million by the year 2030. The massive increase in the number of patients with diabetes is almost entirely due to an increase in type 2 diabetes, caused by insulin resistance among adults and the elderly, rather than the ‘classical’ type 1 diabetes of insulin deficiency that typically starts in childhood. There is much evidence that type 2 diabetes is directly linked to the increased sugar intake that is the hallmark of the Western diet1 and despite much effort on behalf of health ministries and charities, the ‘diabetic tsunami’ shows no sign of stopping.

The basics

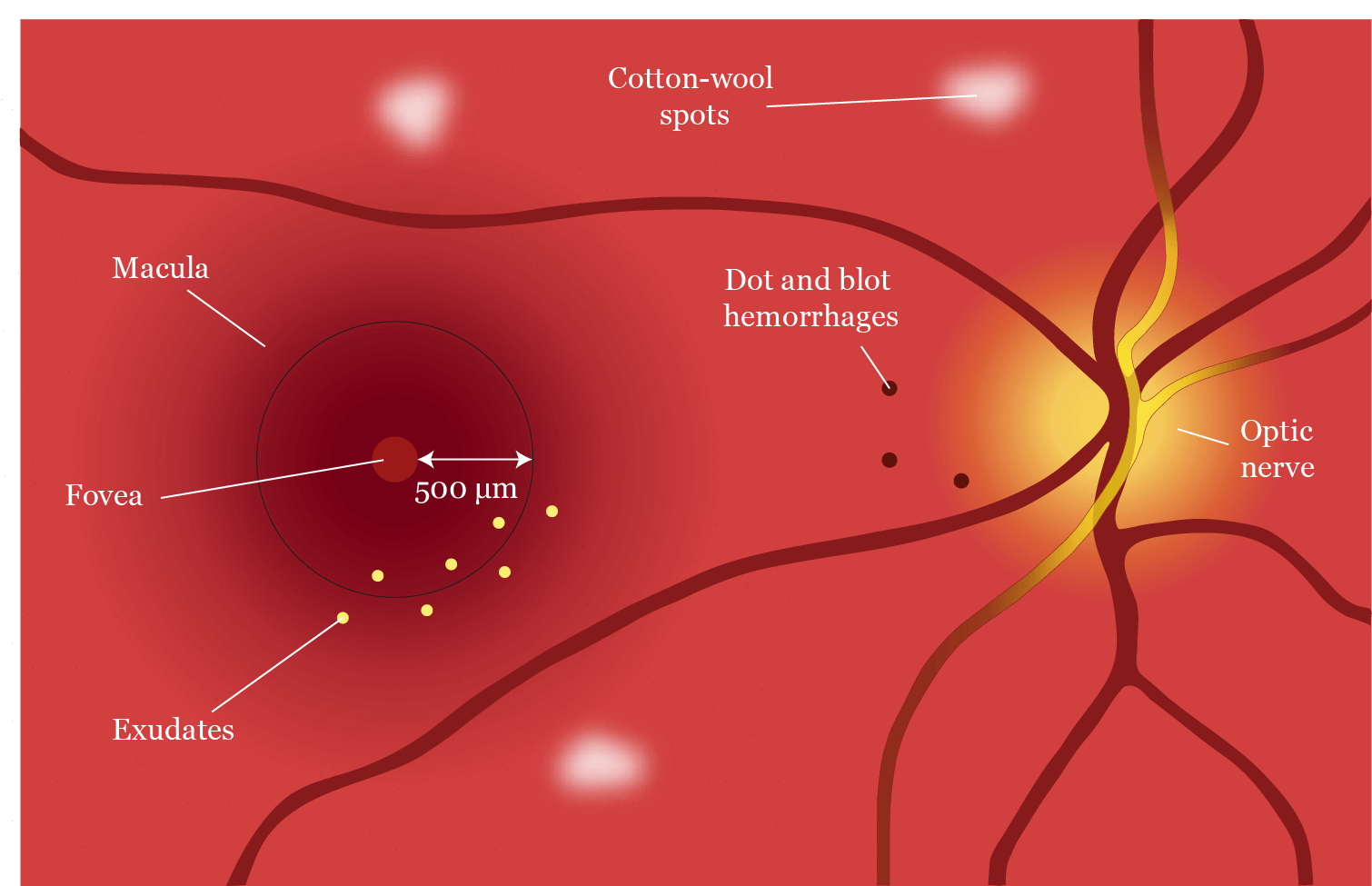

Diabetic maculopathy, rather than proliferative disease, is the main cause of severe sight loss in diabetics. The hallmark Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) defined clinically significant macular edema (CSME) as retinal thickening within 500 μm of the fovea, hard exudates within 500 μm of the fovea if the thickening itself is outside this zone, and a disc diameter of thickening within one disc diameter of the fovea (Figure 1). While this is a clear-cut concept, the definition has moved on to the more nebulous concept of diabetic macular edema (DME) being either ‘diffuse’ or ‘focal’.2 This describes the extent of the edema and unlike CSME has more practical application in how DME is treated, as diffuse leakage was traditionally treated with macular grid laser therapy if fluorescein angiography indicated the level of ischemia was low enough to justify it, and focal leakage was treated with laser therapy that was, well, focal to the area of leakage, unless the leakage involved the fovea alone and laser was too risky.

Figure 1. Diagram representing clinically significant macular edema. Adapted from Schubert. (2013–2014).3

Intravitreal injections of antibodies neutralising vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) and steroids revolutionized the way DME was treated, as edema involving the very centre of the fovea could be treated without the obvious risks that lasering the area involved, and macular grid laser therapy has now become almost obsolete. In fact, there was a debate at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists’ congress recently on whether we should throw away our laser machines now that the injections were known to be so much better. Knowing what the best agent to use is, however, is dependent on a good working knowledge of the pathophysiology behind the condition.

Pathophysiology

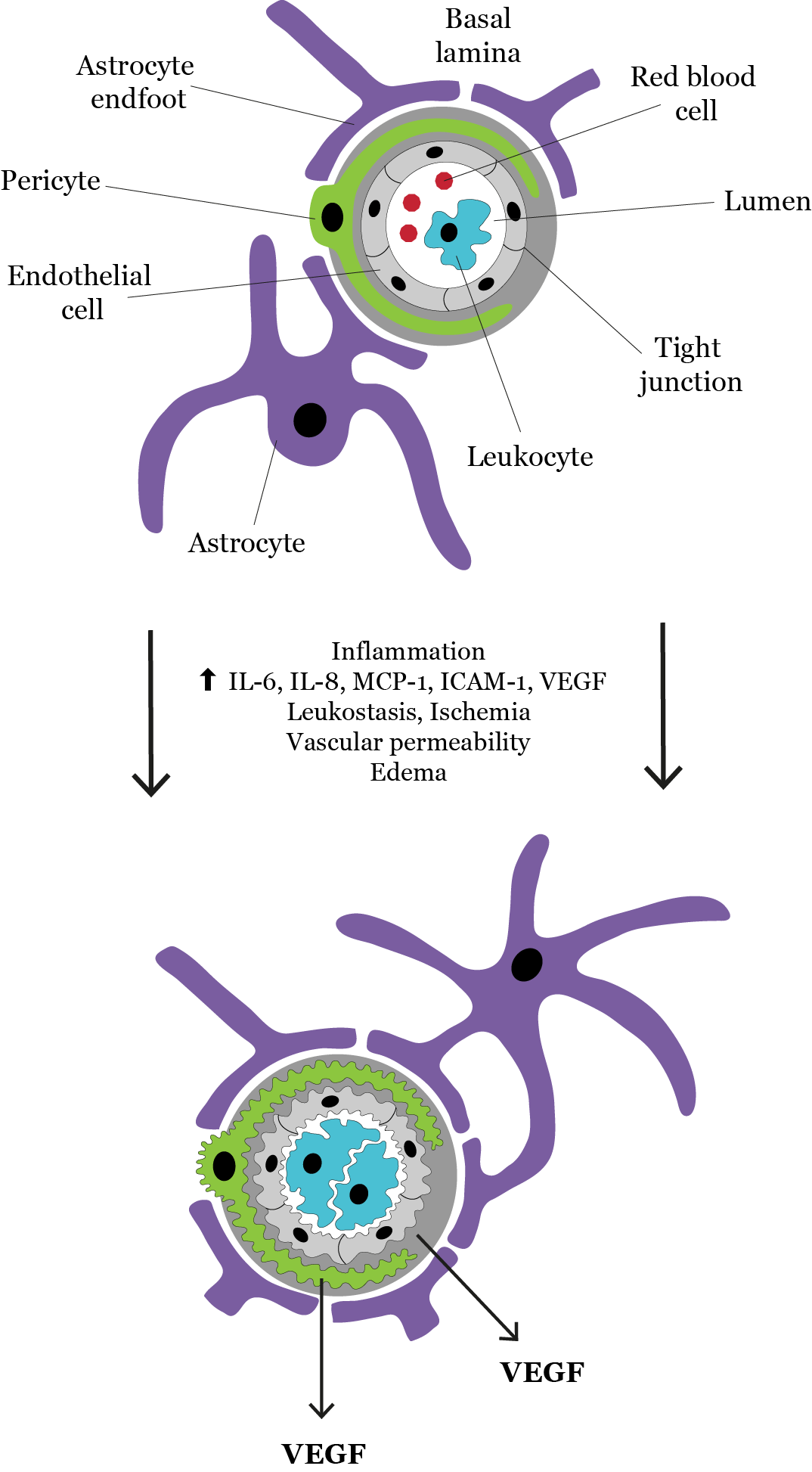

Understanding the blood–retina barrier is essential to understanding why DME occurs. The retina, similar to the brain, requires a very particular physiological environment for the complex cell-to-cell interactions to take place optimally. This is achieved through zonula occludens, or tight junction proteins between the endothelial cells of the retinal vasculature. Occludins, claudins, and junctional adhesion molecules come together to form tight bonds between endothelial cells, which strictly regulate the ionic traffic to and from the retina.4 So long as these tight junctions are maintained, peace and harmony can reign, but any insult to the integrity of these junctions, the so-called ‘waterproofing’ of the blood vessels, can result in a biochemical cascade, which results in cellular damage.

Elevated blood glucose, cholesterol and glycation end products cause an increase in inflammatory mediators, which damage the integrity of the blood–retina barrier. Chief among these, particularly in the early stages, is VEGF-A, the release of which is directly correlated with lower expression of zonula occludens proteins and thus increased vascular permeability (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagram representing inflammation and vascular dysfunction in diabetic macular edema. Adapted from Abcouwer. (2013).5

VEGF-A in turn up-regulates the expression of intracellular adhesion molecules on the endothelial surface, resulting in leukostasis, where inflammatory cells adhere to the areas of damaged endothelium and start releasing a host of inflammatory mediators.6 These include interleukin 6, tumour necrosis factor and cyclo-oxygenase 2. While VEGF-A is a prominent factor in the initial development of DME, it takes a backseat in chronic edema, as multiple other inflammatory cycles establish themselves and the situation becomes infinitely more complicated.4

Diagnosis

While the pathophysiology, particularly in the later stages, is increasingly complicated and difficult to understand, the diagnosis is usually not. Clinically, the patient may complain of blurred vision and distortion, and examination of the fundus may reveal the telltale signs of vasculopathy associated with diabetes. Microaneurysms and dot and blot haemorrhages are testament to damage to the endothelial walls, while the result of this is leakage of serous fluid and deposition of lipids in the outer plexiform layer – the easily identifiable ‘hard exudates’. If these occur within the macula, then DME is said to exist, and CSME has a very specific definition, as mentioned above. These are clinical diagnoses, identified during slit lamp biomicroscopy. The advent of ocular coherence tomography scanning has made the quantification of the edema infinitely more accurate than in days past, with the measuring of central retinal thickness to the micrometer now possible. This is particularly important, as National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines in the UK advocate the use of certain anti-VEGF agents in DME patients only if central retinal thickness is at least 400 μm.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) has a role in diagnosing DME as well – two roles, in fact. First, and perhaps obviously, FFA demonstrates leakage in the macula associated with diabetic eye disease and can help guide the application of laser to the correct place. Second, it can demonstrate ischemia of the fovea in the form of an increased foveal avascular zone, pruning of vessels and capillary dropout. This can help predict the likely improvement to vision should the edema be treated and whether, to be blunt, the effort is worth it for the patient. Diagnosis, however, is one thing; what the patient really wants to know is how it can be treated.

Chronicity and treatment

Before moving on to treatment, it is important, however, to have a handle on the duration of the edema – the chronicity – as this has a major impact on the effectiveness of various treatments available. While VEGF-A is a prime factor in the initial breakdown of the blood–retina barrier and the mediation of early macular edema, it is overshadowed by more complex inflammatory pathways as the disease becomes more established, as detailed above. It stands to reason, therefore, that if macular edema is caught early, then anti-VEGF agents, injected directly into the eye, can be associated with significant benefit and countless data are available that back this up, derived from large clinical trials such as RESOLVE, READ-2 and RESTORE.7,8,9 Studies have also shown that injection of intravitreal steroids can be of benefit in DME, with the results becoming more significant with greater duration of edema, as observed in the FAME study.10

Despite the emergence of new therapies for DME, there is still a need to treat the underlying disease. Attention must therefore be paid to one of the most important factors of all: diabetic control and hypertension. Both the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial for patients with type 1 diabetes11 and the UK Prospective Diabetes Study for those with type 2 diabetes12 clearly demonstrated the importance of controlling blood glucose and blood pressure. This is of such vital importance, yet is often overlooked in a busy diabetic eye disease clinic, as we use our new technology to see if newer medications can be used. In a similar vein, it is still perfectly acceptable to use laser therapy for focal leakages threatening the fovea, although of course DME only affecting the fovea cannot be treated this way.

The complicated inflammatory cascades involved in DME are being increasingly well understood each year, and new and exciting therapies can treat the once untreatable. This is not a moment too soon either, as the diabetic tsunami engulfing humanity is upon us and ophthalmologist everywhere need to rise up to the challenge and be part of a global solution to a global challenge.

Gwyn Williams (MBBS DOHNS DHMSA BSc MRCS [Eng] FRCOphth) trained on the Wales rotation and is now a medical retina fellow at Moorfields Eye Hospital.

Look out for DME content developed by Alimera Sciences on this website throughout 2015. We hope it supports your knowledge of DME, and if you would like to contribute material for publication, please send your materials to dmecontenthub@hayward.co.uk, and we’d be very pleased to consider your contributions.

REFERENCES

1. RJ Johnson et al., “Sugar, uric acid and the etiology of diabetes and obesity”, Diabetes, 62, 3307–3315 (2013). PMID: 24065788. (http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/content/62/10/3307.long)

2. DJ Browning et al., “Diabetic macular edema: what is focal and what is diffuse?”, Am J Ophthalmol, 146, 649–655 (2008). PMID: 18774122. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2785449/)

3. HD Schubert, "Retina and Vitreous", Basic and Clinical Science Course, Section 12. American Academy of Ophthalmology: 2013–2014. Courtesy of ETDRS.

4. X Zhang et al., “Diabetic macular edema; new concepts in patho-physiology and treatment”, Cell Biosci, 4, 27 (2014). PMID: 24955234. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4046142/)

5. SF Abcouwer, "Angiogenic Factors and Cytokines in Diabetic Retinopathy", J Clin Cell Immunol, Suppl 1, 11 (2013). PMID: 24319628.

6. N Bhagat et al., “Diabetic macular edema: pathogenesis and treatment”, Surv Ophthalmol, 54, 1–32 (2009). PMID: 19171208.

7. P Massin et al., "Safety and efficacy of ranibizumab in diabetic macular edema (RESOLVE Study): a 12-month, randomized, controlled, double-masked, multicenter phase II study", Diabetes Care, 33, 2399–2405 (2010). PMID: 20980427.

8. QD Nguyen et al., "Two-year outcomes of the ranibizumab for edema of the mAcula in diabetes (READ-2) study", Ophthalmology, 117, 2146–2151 (2010). PMID: 20855114.

9. P Mitchell et al., "The RESTORE study: ranibizumab monotherapy or combined with laser versus laser monotherapy for diabetic macular edema", Ophthalmology, 118, 615–625 (2011). PMID: 21459215.

10. PA Campochiaro et al., “Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts provide benefit for at least 3 years in patients with diabetic macular edema.” Ophthalmology, 119(10), 2125–2132 (2012). PMID: 22727177.

11. NH White et al., “Effect of intensive therapy in Type 1 diabetes on 10-year progression of retinopathy in the DCCT/EDIC: comparison of adults and adolescents”, Diabetes, 59, 1244–1253 (2010). PMID: 20150283. (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2857905/)

12. P King et al., “The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS): clinical and therapeutic implications for type 2 diabetes”, Br J Clin Pharmacol, 48, 643–648 (1999).

UK-ILV-MMM-0373 Date of preparation: September 2015

Founded in 2003, Alimera Sciences researches and develops innovative vision-improving treatments for chronic retinal diseases, such as diabetic macular edema (DME), dry age-related macular degeneration (AMD), and retinal vein occlusion. In 2015, Alimera Sciences partnered with The Ophthalmologist to facilitate the publication of independently created educational content surrounding DME, a serious retinal complication associated with diabetes, which is increasing in incidence with the increasing prevalence of diabetes worldwide. Published content will include articles ranging from basic science and disease processes to overviews of clinical data, different surgical procedures, comparisons of treatment options, and practical advice for managing diabetic patients. With a commitment to honesty, integrity, responsibility, candor, and trust, Alimera Sciences intend to provide educationally focused content to healthcare professionals across a wide range of topics in DME in order to both increase disease awareness and understanding, and to help improve patient outcomes. UK-ILV-MMM-0355 Date of preparation: August 2015 enquiries@alimerasciences.com