Diabetic macular edema (DME) poses a significant management dilemma for visual impairment. We present a challenging case of persistent, bilateral maculopathy. The patient’s diabetic parameters were poor, and laser photocoagulation had failed. A recent stroke precluded ranibizumab use. A fluocinolone implant was considered to save his vision. No similar reports have to date been published.

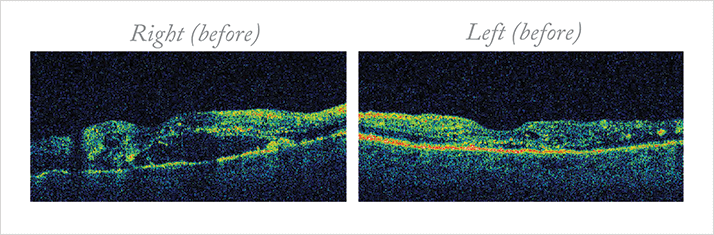

Case Presentation A 54-year-old schizophrenic man presented with bilateral proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) and DME. He noticed gradual, painless blurring of vision for several months, with recent profound loss of vision in his right eye. Three years earlier, he had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Following a period of erratic control, aggravated by poor compliance, he recently tightened his control. His medications included gliclazide, lisinopril, and sulpiride. His Snellen VA was right count fingers and left 6/36. Slit lamp examination revealed mild cataracts and aggressive PDR and DME. Other causes of poor vision were excluded. Management and outcome Optical coherence tomography (OCT) confirmed right diffuse DME and left focal edema (Figure 1). Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) identified mixed maculopathy. The patient had elevated blood pressure (185/87) with HbA1c 70 mmol/mol, and an acute decline in renal function with significant albuminuria and normochromic normocytic anemia.

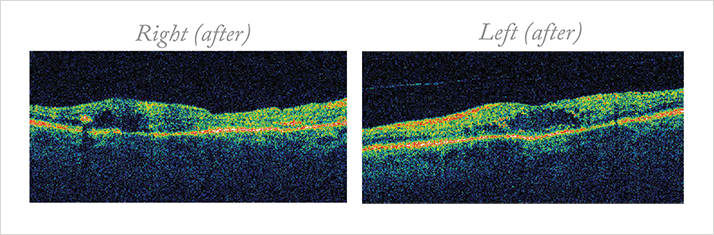

He had urgent bilateral panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) and concurrent macular laser with the Pascal system. Over the next 20 months, he received four PRP and four macular lasers (three grid, one focal) to his right and left eyes (two grid, two focal). Serial VA, fundoscopy, and OCT were monitored at three-month intervals. Nearly two years after his presentation, his right VA remained poor, but his left VA improved to 6/24. OCT confirmed the persisting DME (Figure 2).

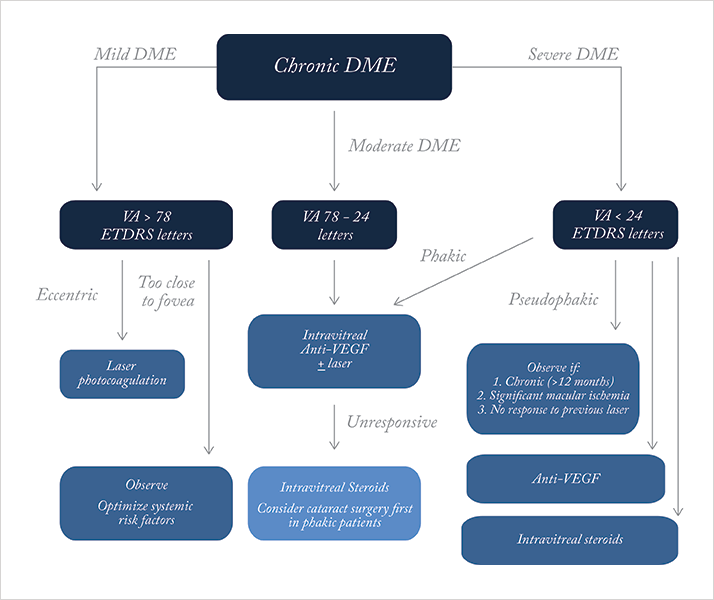

A recent stroke precluded anti-VEGF use. Scotland recently approved a fluocinolone implant, and we await local use. Continued holistic, multidisciplinary care with diabetologists should optimize his prognosis. Discussion Detecting DME requires careful examination with high magnification, stereoscopic biomicroscopy (e.g., 78D lens). VA is best measured with the ETDRS chart, but the Snellen is widely used. OCT provides information on retinal swelling, central retinal thickness, morphology (e.g., cystoid) and vitreo-macular traction. FFA identifies leakage, extent, and macular ischemia. Figure 3 shows our recommended treatment approach: we suggest two- to four-month reviews to assess VA, fundoscopy, and OCT +/- FFA. Patients with severe DR warrant earlier intervention. FFA should be repeated if ischemia is suspected of limiting the treatment response. Patients with poor response show mixed maculopathy, extensive macular ischemia, severe retinopathy, diffuse disease, uncontrolled hypertension, renal disease and increased Hba1c levels.

Lasers remain the mainstay of therapy, but do not routinely restore lost vision. Some eyes appear refractory to treatment. Potential complications include transient increased edema, scars and foveal non-perfusion after repeated treatments. Microalbuminuria and anemia are risk factors for DR severity and progression, increasing cardiovascular and stroke risks (1). Aim for Hba1c <6.5%, and BP 130/80 with co-existing nephropathy. Fenofibrates should be considered. Ranibizumab improves and restores vision and slows DR progression (2,3). Multiple injections are required, and there is a small risk of stroke (4,5). According to drug manufacturers’ information, ranibizumab use is contraindicated following stroke. Intravitreal triamcinolone is associated with significant adverse events, including elevated IOP and cataracts (6). Long-term effects, even at two years, show no significant benefit (7). Fluocinolone acetonide (Iluvien) has recently been licensed in Scotland for pseudophakic chronic DME cases unresponsive to other options. This non-biodegradable intravitreal implant is designed to release lower sustained doses (0.59 μg/ day) of fluocinolone for up to 36 months (8). In the FAME study, 34 percent of subjects gained ≥ 3 VA lines (8). We plan to perform cataract surgery during his fluocinolone implantation. Concurrent bilateral implantation is not recommended, although an additional implant might be administered after 12 months of worsening DME. Ophthalmologists should practice on a model eye to get a feel for the preloaded applicator. Sterile techniques should be used to place the implant inferior to the optic disc and posterior to the equator. Successful placement after insertion should be verified with indirect ophthalmoscopy. Optic nerve perfusion, IOP retinal detachment and endophthalmitis must be checked immediately post injection and two to seven days later. IOP, VA and lens clarity should be monitored every three months. Patients who sustain IOP elevation might require IOP lowering drops, laser trabeculoplasty or surgery. Conclusions We presented a challenging case with severe maculopathy in both eyes that was unsuitable for ranibizumab and heading toward steroid implant treatment relatively soon. Fluocinolone’s place in chronic DME therapy adds to a new range of treatment options for recovering vision in previously hard-to-treat patients. Statement: Patient consent was obtained.

Read the next case report

References

- T.M. Diep, I. Tsui, "Risk factors associated with diabetic macular edema", Diab. Res. Clin. Pract., 100(3), 298-305 (2013). F. Bandello, L. Berchicci, C. La Spina, et al., "Evidence for anti-VEGF treatment of diabetic macular edema". Ophthal. Res. 48(S1), 16–20 (2012). L.P. Aiello, R.W. Beck, N.M. Bressler, et al., "Rationale for the diabetic retinopathy clinical research network treatment protocol for center-involved diabetic macular edema", Ophthalmol. 118(12), e5–14 (2011). G. Virgili, M. Parravano, F. Menchini, et al., "Antiangiogenic therapy with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor modalities for diabetic macular oedema", Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12, CD007419 (2012). N.M. Bressler, D.S. Boyer, D.F. Williams, et al., "Cerebrovascular accidents in patients treated for choroidal neovascularization with ranibizumab in randomized controlled trials", Retina 32(9), 1821–1828 (2012). M.W. Stewart, "Corticosteroid use for diabetic macular edema: old fad or new trend?", Curr. Diab. Rep. 12(4), 364–375 (2012). T. Yilmaz, M. Cordero-Coma, A.J. Lavaque, et al., "Triamcinolone and intraocular sustained-release delivery systems in diabetic retinopathy", Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 12(3), 337–346 (2011). P.A. Campochiaro, D.M. Brown, A. Pearson, et al., "Sustained delivery fluocinolone acetonide vitreous inserts provide benefit for at least 3 years in patients with diabetic macular edema", Ophthalmol. 119(10), 2125–2132 (2012).