- Proving that your idea is novel and inventive is key to obtaining a patent

- You need to understand your obligations when negotiating contracts – and set your expectations accordingly

- Regulatory affairs: understand what regulatory bodies need from you is central to gaining approval

- Hard decisions: do you finance and develop yourself, or license or sell your innovation?

Necessity is the mother of invention: a problem needs solving, someone has a good idea, an invention is born. In clinical medicine, ideas often arise from the act of treating a patient; someone considers how to improve a treatment modality’s speed, efficiency or both – an invention is born. Notably, the more straightforward the idea, the more likely it is to be realized or translated into practice. Here, I discuss the four important milestones along your commercialization journey, and highlight what you need to consider to stand the best chance of success.

1. Patents: is your idea novel and inventive? Once you’ve had your idea or developed your invention, you’ll likely want to protect your intellectual property (IP) with a patent. A patent represents a limited monopoly. From an IP perspective, an invention must satisfy two criteria for a patent to be granted: it must be (i) novel and (ii) useful or inventive. Proving that your invention is novel is almost always the hardest obstacle when trying to obtain a patent for a medical device or a pharmaceutical entity. Novelty is defined as being clear of any prior art before the actual filing date of the patent application. What do we mean by “prior art”? The term includes (but is not limited to) any public presentation, scientific publication, poster, or any other form of public information about the invention. Before going down the long and potentially expensive path of patenting your invention, you need to check for prior art (or even potential patent infringement) – and this no simple task. The first step is to search – extensively. There are publicly available online databases (such as the European Patent Office, http://www.epo.org/searching.html, or Google Scholar, http://scholar.google.com/), but there are many other search options, and sometimes it can be worthwhile paying for a search report to be performed by a national IP institute.

The art of drafting a patent application is a seemingly contradictory balance. On the one hand, you must include as much of the area surrounding the patent as possible without infringing on any other IP or including prior art, but at the same time be sparing or even vague with sensitive information to reduce the risk of a simple “invent-around.” It’s actually this delicate balance that becomes the major pitfall for many first-time inventors, who usually want to include everything in their application in the hope of receiving a limited monopoly on their idea or invention. However, what usually happens is that after 18 months from the filing date – which is not usually enough time to develop and bring a medical device to market – the application is published and potential competitors receive information to facilitate a market counter-attack. For them, the more proprietary information included the better! Of course, if the invention is not properly covered by the patent in terms of specific claims, then it can be hard to enforce, which is not good either. In the medical devices field, most people consider IP the safest insurance an inventor can have. But there are some companies that bring medical devices to market without any IP protection at all. Such companies compensate with rapid speed of entry to the market, “podium power”, and (later) competitive prices to maintain their market share. The latter often proves to be the challenging part; it’s incredibly difficult to maintain a high market share with no IP, because you make it easy for competitors – they’ve seen what you’ve done, and there’s nothing stopping them from copying you.

2. Contracts: double-check your rights and obligations Shuji Nakamura was one of the three recipients of the 2014 Nobel Prize for Physics “for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes, which has enabled bright and energy-saving white light sources”. His discovery, which made the blue LED possible, came in the 1990s when he was working in his spare time, but his employer, Nichia Corporation, took the rights to the discovery – as per the terms of his employment. They paid him a bonus of ¥20,000 (€150) at the time – and may have made over US$1.1 billion in profits from the invention since then… The lesson? You must seriously consider your employment contract before filing for patent. For inventors working in academic institutions both in the US and the EU, contracts explicitly state that all IP generated is fully owned by the university. However, the inventor has the right to license the technology – the “right of first refusal”. If the university decides not to pursue IP rights for an invention, then the inventor is free to do so at his or her own risk and expense. Industrial collaboration agreements that specifically refer to any IP generated (in an exclusive field) for the duration of the collaboration must also be considered carefully. Often, when industry provides funding for a researcher, the company has a specific paragraph in their agreement that protects the company’s interests. Specifically, the paragraph would state that the company would either own the right to license – the right of first refusal – in the case of an academic collaboration or “work made for hire”, which states that the company is paying for the researcher’s services and owns anything that results from their work. These contract obligations are not necessarily a bad deal for the inventor. Often, the academic institute has a technology transfer office that will offset the costs of the patent drafting and submission fees until a licensing agreement is secured. These offices have a team of advisors that judge the technology’s market worth, meaning that the motivation for a technology transfer office to approve the payment of these fees will be determined by how fast the funds would be recuperated in a potential licensing agreement. In the case of industrial agreements, the inventor is almost always named on the patent application, and may receive compensation in the form of a consultancy – or in some cases a non-compete clause to deter “re-invention”.

3. Regulations: how to approve your invention in Europe and North America Although you think you’ve solved a problem or made something better, you now have to prove it. Depending on the type of invention, this step may be the most time- and money-consuming. Europe In the case of a medical device in Europe, ultimately, the extent of the proof will be dependent on the regulatory body responsible for issuing a CE mark. If you can prove to the regulatory bodies that your invention is similar to a device already on the market (with similar product specifications), then the threshold may be met. If there is nothing similar on the market for the medical indication, then a scientific file, with peer-reviewed publications, will be required. The more supporting information submitted, the higher the chances of a rapid decision in favor of a CE mark. However, if you do not convince the regulatory body of the already proven safety and efficacy of the treatment/device, then you will most likely need to start conducting research to create a scientific file. Sometimes, a full clinical trial will be needed, which translates into many years and significant financial burden.

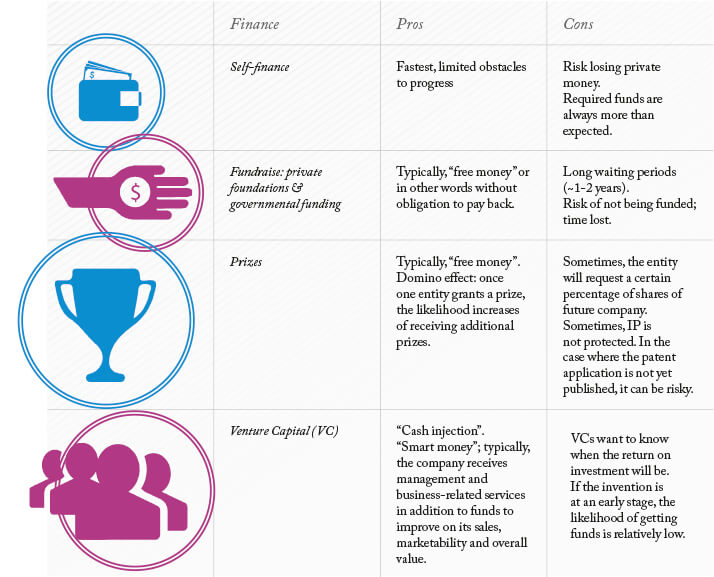

North America While the same basic principle holds true in North America, especially in the US, the FDA can be more rigorous with its requirements. In fact, the expectation of long delays and large expenses related to the approval process leads some ophthalmic companies to forgo the process altogether and not sell in the US. In particular for non-US start-up companies, the amount of funding and know-how required to enter the US can be too much to handle in the first 5–10 years of business. Unfortunately, though the FDA’s rigorous requirements can result in higher safety standards for its citizens, it can sometimes come at an expense: cutting-edge treatments or devices may be delayed or simply never become available. 4. Crossroads: finance/develop or license/sell? As noted, the capital required to conduct research for regulatory approval can be substantial, so you may find yourself at an all-important crossroads. There are several ways of raising funds but, fundamentally, you must determine what is really feasible. Table 1 offers funding options alongside their advantages and disadvantages.

If the finance and development route seems too daunting or simply impossible, you are probably interested in licensing (or selling) the invention. Once again, there are a number of considerations that need to be taken into account to maximize the earning potential. For a medical device-related invention, you should consider:

- What exactly are you trying to protect? And who do you want to avoid knowing the secrets of your invention? Why?

- Who/what would benefit from your invention? (For example, who: patient, distributor, user/surgeon, manufacturer; what: faster, safer, easier, improved outcomes, cheaper, smaller, lighter).

- Would your invention help sell existing procedures or machines/devices?

- What companies already have existing technology? Does the invention improve the company’s existing procedure/treatment? If not, would a competing company be interested in entering the market?

- Can your invention be translated into any other fields or applications? Why or why not?

Be a businessperson The “crossroads” is always difficult because it forces you into a new role. You must learn to separate the invention from your own idea and start treating it as a business idea/concept that needs financing. From my personal experience, nothing slows down the progress of bringing a product to market more than the emotions and attachment of the inventor. Therefore, a pivotal question at this stage is: are you ready for your new role of businessperson? In summary, when translating an idea into a possible commercial product, you must consider these four key aspects. My guidance here is based on my personal experience of working with and for academic institutions in North American and Europe, primarily in the medical device sector, so, as a caveat, I should say that each invention should be treated individually. All ideas/inventions have special circumstances, so it is important to adapt any guidance accordingly. As a final word, I cannot recommend enough that it is important to include as many experts in the respective field as possible to assist you through the initial processes. You’ll save time (and money), which will come in very handy to further develop the invention and, hopefully, your start-up company.

Nikki Hafezi is the managing director of GroupAdvance Consulting GmbH and the CEO of EMAGine AG; both companies are based in Zug, Switzerland.