It’s a fact that a significant proportion of patients with glaucoma either are, or will become, sensitive to the preservatives present in their topical glaucoma medications. This will typically manifest as ocular surface disease (OSD), typically dry eye disease (DED) (1,2), something that’s already highly prevalent in the general population, and like glaucoma, has an incidence that rises as people age – which in the case of DED, ranges from 5 to 30 percent in people aged 50 years and older (3). When glaucoma or ocular hypertension is added into the equation, this statistic skyrockets: as many as 60 percent of patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension may have OSD, and as many as a third will have the severe form (4). Further, if a patient has glaucoma and DED, they are up to 12 times more likely to experience symptoms related to OSD like foreign-body sensation, relative to glaucoma patients without DED (5).

When preservatives are the problem

The development of OSD doesn’t appear to be a function of glaucoma per se, rather, it’s related to the type, number and duration of topical glaucoma medications that the patient receives: several studies have shown that there’s a higher prevalence of OSD like dry eye or allergy in patients with glaucoma treated over the long-term, and the prevalence rises as the number of topical medications increases. This rise has been linked to preservatives used in glaucoma medications rather than the active substances, and can considerably and negatively impact on patients’ quality of life (2, 4–7). The elephant in the room is BAC: benzalkonium chloride, a surfactant that’s commonly used in eyedrops as a preservative and bactericide. It dissolves bacterial cell membranes – but it can also have a deleterious effect on the ocular surface, and can be allergenic. As this often results in the patient experiencing symptoms of OSD – like itching, irritating or foreign-body sensations (5) – it obviously has an effect on patients’ regimen compliance, and ultimately, IOP control (8,9). One of the reasons why BAC can cause ocular surface disorders is through goblet cell loss. Goblet cells are the main source of ocular surface mucoproteins and play a central role in tear film stability (10). They have been shown to diminish in number following exposure to BAC-containing topical glaucoma therapies (10,11), and it’s thought that this leads to decreased mucin production, tear film instability and ultimately, in many cases, OSD (12).When preservatives are the problem

The development of OSD doesn’t appear to be a function of glaucoma per se, rather, it’s related to the type, number and duration of topical glaucoma medications that the patient receives: several studies have shown that there’s a higher prevalence of OSD like dry eye or allergy in patients with glaucoma treated over the long-term, and the prevalence rises as the number of topical medications increases. This rise has been linked to preservatives used in glaucoma medications rather than the active substances, and can considerably and negatively impact on patients’ quality of life (2, 4–7). The elephant in the room is BAC: benzalkonium chloride, a surfactant that’s commonly used in eyedrops as a preservative and bactericide. It dissolves bacterial cell membranes – but it can also have a deleterious effect on the ocular surface, and can be allergenic. As this often results in the patient experiencing symptoms of OSD – like itching, irritating or foreign-body sensations (5) – it obviously has an effect on patients’ regimen compliance, and ultimately, IOP control (8,9). One of the reasons why BAC can cause ocular surface disorders is through goblet cell loss. Goblet cells are the main source of ocular surface mucoproteins and play a central role in tear film stability (10). They have been shown to diminish in number following exposure to BAC-containing topical glaucoma therapies (10,11), and it’s thought that this leads to decreased mucin production, tear film instability and ultimately, in many cases, OSD (12).Theory versus reality

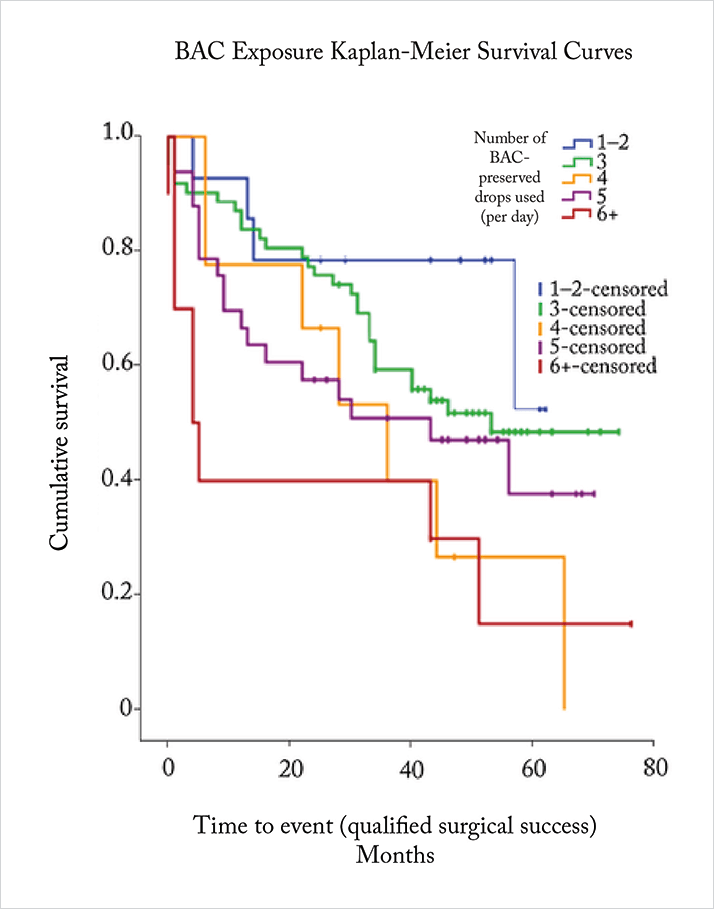

One thing is clear: BAC doesn’t improve the efficacy of the eyedrops (13). In theory, it might: BAC is a penetration enhancer, and greater penetration should bring greater efficacy. Clinical study data show that the reality is different. For example, Hamacher et al. (14) examined the efficacy of preservative-free (PF)- and BAC-preserved tafluprost in a four-week crossover study in patients (n=43) with open-angle glaucoma or ocular hypertension, and found that these formulations had equal efficacy (p=0.96). Shedden et al. (15) also found no difference in the IOP-lowering effect of PF- and BAC-preserved carbonic anhydrase inhibitor/β-blocker fixed combination eyedrops, in a trial that randomized 261 glaucoma patients to either drug. There’s another problem: the number of BAC-containing topical glaucoma medications and the duration of therapy with them can also negatively impact upon the success rates of glaucoma filtration surgery (7, 16–18) (Figure 1). It appears that even postoperatively, the ocular surface inflammation that was induced by presurgical topical therapy continues to play an important role. The conjunctiva interacts with aqueous humor, and subconjunctival fibrosis can lead to aqueous outflow blockage, resulting in trabeculectomy failure (17). Clearly, this is important because surgery is often necessary to control IOP in a great number of patients who have previously received chronic, topical glaucoma therapy (17). In recognition of the extent of these issues, the European Glaucoma Society (EGS) advise that “particular attention should be paid to glaucoma patients with pre-existing OSD or to those developing dry eye or ocular irritation over time” (19). Further, the European Medicines Agency recommends avoiding preservative-containing topical therapies in patients who do not tolerate eye drops with preservatives, and considering the use of formulations without preservatives as a valuable alternative for long-term treatment (20).Spotting the symptoms

Clearly, it’s important to find these patients and switch their medications wherever possible, as soon as possible. So how do you identify them? Stalmans et al. (21) suggest a few quick steps. The first thing to do – before any examination – is to take the patient’s history. Ask the patient about any factors that might impair ocular surface function, and if you don’t already have the information, ask the patient about any other ocular disorders they may have been previously diagnosed with, and what other ocular topical therapies they may be taking. Finally, ask about dry eye symptoms: do they have discomfort along the lines of a “recurrent sensation of sand or gravel in their eyes”, or visual disturbances such as contrast sensitivity, decreased visual acuity and increased optical aberrations? Next, perform a series of quick glances examining the ocular surface, eyelids and periocular skin for signs of meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD), abnormal tear film meniscus positioning, hyperemia, or debris at the canthi. Follow this with a slit lamp examination, checking the lid margins for signs of MGD, meibomitis or blepharitis; the tarsal conjunctiva for surface abnormalities; and lid laxity causing possible malpositions. Finally, conjunctival fluorescein staining can be used to assess tear film stability (break-up times of <10 seconds are considered abnormal) and identify any damage to the corneal epithelium.Keep the lines of communication open

These simple steps will help identify those patients who will benefit from preservative-free topical glaucoma therapy. Although many patients with glaucoma receive preservative-containing topical medications and don’t have OSD, continual review of these patients is advised – consider taking the time to explain the issues that the preservatives in their medications can sometimes cause, and alerting them to the early signs of OSD (21). Dialog between you and your patient could mean timely switching to preservative-free therapies, reducing the potential in some patients for poorer clinical outcomes.Job code: STN 1117 TAP 00025 (eu).

Date of preparation: November 2015.

References

- C Baudouin, et al., Prog Retin Eye Res, 29, 312–334 (2010). PMID: 20302969. RD Fechtner, et al., Cornea, 29, 618–621 (2010). PMID: 20386433. JA Smith, et al., Ocul Surf, 5, 93–107 (2007). EW Leung, et al., J Glaucoma, 17, 350–355 (2008). PMID: 18703943. C Erb, et al., Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 246, 1593–1601 (2008). PMID: 18648841. GC Rossi, et al., Eur J. Ophthalmol, 4, 572–579 (2009). PMID: 19551671. DC Broadway, et al., Arch Ophthalmol, 112, 1446–1454 (1994). PMID: 7980134. B Sleath, et al., Ophthalmology, 118, 2398–2402 (2011). PMID: 21856009. P Denis, et al., Clin Drug Investig, 24, 343–352 (2004). PMID: 17516721. L Mastropasqua, et al., Acta Ophthalmol, 91, 397–405 (2013). PMID: 23601909. MY Kahook, R Noecker, Adv Ther, 25, 743–751 (2008). PMID: 18670744. G Van Setten, et al., European Ophthalmic Review, 8, 87–92 (2014). M Irkec, et al., Br J Ophthalmol, 97, 1493–1494 (2013). PMID: 24216677. T Hamacher, et al., Acta Ophthalmol Suppl, 242, 14–19 (2008). PMID: 18752510. A Shedden, et al., Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol, 248, 1757–1764 (2010). PMID: 20437244. DC Broadway, et al., Arch Ophthalmol, 112, 1437–1445 (1994). PMID: 7980133 C Baudouin, Dev Ophthalmol, 50, 64–78 (2012). PMID: 22517174. C Boimer, CM Birt, J Glaucoma, 22, 730–735 (2013). PMID: 23524856. European Glaucoma Society, “Terminology and Guidelines for Glaucoma – 4th Edition”, EMEA/622721/2009 (2014). Available at: bit.ly/egs2014. Accessed September 29, 2015. European Medicines Agency, “EMEA public statement on antimicrobial preservatives in ophthalmic preparations for human use” (2009). Available at: bit.ly/EMA2009, accessed October 03, 2015. I Stalmans, et al., Eur J Ophthalmol, 23, 518–525 (2013). PMID: 23483513.