- Microsoft no longer supports or updates Windows XP with security patches

- Many PCs across the world still run it – including ones used in the clinic

- Unpatched XP on PCs represents huge (and easy) pickings for hackers

- We explore what this means for you if you still have PCs and instruments that run XP

August 24, 2001 saw the launch of Windows XP. Almost 13 years later, on April 8, 2014, Microsoft ended its “Extended Support” phase for the operating system. Given that on that date, roughly a third of all PCs had Windows XP as their operating system, that was an awful lot of people to cut loose – no more security patches, no support information, nothing. Microsoft, however, is continuing to patch security vulnerabilities in Windows XP, though, but not for individuals. If you’re a big corporate customer, however, you can purchase “Custom Support”, for a cost of ~US$200 per PC per year. For example, the UK Government paid Microsoft £5.5 million last April for a year’s worth of Custom Support for national and local government, education and the National Health Service – but won’t renew the contract again this April. It will be interesting to see what happens next.

You can be certain that all devices that run software have the potential to be exploited – even the microcontrollers of your camera's SD card is at risk (bit.ly/CCCSD). The latest versions of Windows and Mac OS X will have security holes that hackers will find and exploit. Both Microsoft and Apple will close these holes as soon as they can after they discover them; it’s a cat-and-mouse game between them and the hackers. The problem with Windows XP, is that Microsoft has essentially given up on their part of the game, even though hundreds of millions of people still use it – and many of those work in healthcare.

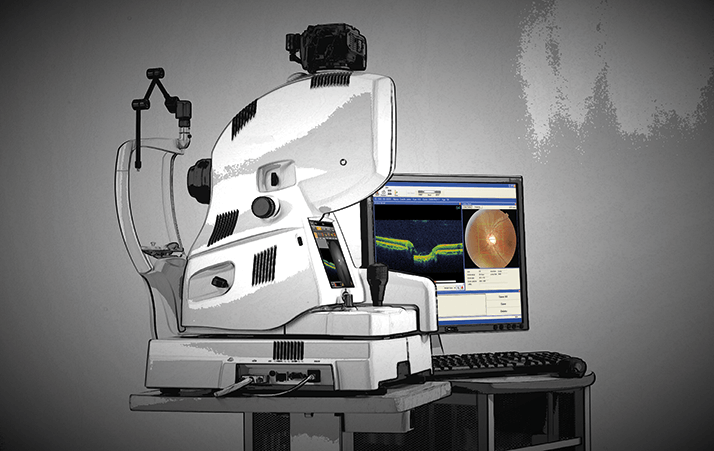

Windows XP was the de facto PC operating system for just over eight years, from early 2001 until Windows 7 was launched in late 2008 (Windows Vista, when launched in 2006, just didn’t sell well). This meant that there was the best part of a decade where medical instruments were being built, and bespoke applications written, to work on Windows XP (Figure 1). Most medical instruments have a non-trivial cost attached to them – so if they continue to work, or it’s cheaper to fix, for example, a corneal topographer that cost €100,000 than it is to replace it, then in these austere times, they’re likely to continue to be used until they absolutely have to be replaced.

What do hackers want?

The bad guys want control of your PC for a number of reasons. If it’s on the internet, it can participate in a botnet, and be told to do any number of nefarious tasks, like denial of service attacks, where your PC, in concert with many others, bombards servers with so many requests for information, it can’t function (just like what happens organically to ticket websites the moment after tickets for a popular event goes on sale). They could use your PC to mine Bitcoins – earning a virtual currency for them, at the expense of your electricity bill. Or they could use it to infect other computers – botnets can be rented out and can represent a good hacker revenue stream. Media like CDs, DVDs, USB flash or external hard drives are another method of malware propagation. The most prominent example is Stuxnet – a worm (self-replicating and propagating computer virus) that targeted the systems controlling Iranian nuclear centrifuges (and ruined a fifth of them). It was introduced into their nuclear facility on a USB flash drive, reportedly by an Iranian double agent working for the Israeli secret service, and once Stuxnet was on their internal network, it could propagate and update itself profusely (bit.ly/thestuxnet).Hackers also love hacking healthcare. It’s viewed as insecure and easy to hack (see below; bit.ly/easytohack) and there’s two strands of data to mine: financial and personal. The second-biggest health insurer in the US, Anthem, was hacked last month, reportedly by Chinese state-sponsored hackers. The information taken reportedly included names, birthdays, social security numbers, street addresses, email addresses and employment information, including income data (bit.ly/anthemG) – certainly enough to commit fraud. Irrespective of location, though, health records are a rich database of proclivities, health concerns, prescription (or illegal) drug use and in some cases, some seriously private information that could be used to smear or blackmail people. And it’s quite possible your instrument or PC running Windows XP is on the same network as computers that health records are accessed from… Network security is already important, and with hackers increasingly focusing on healthcare as a target, its importance is only going to increase.

Can’t you just upgrade Windows?

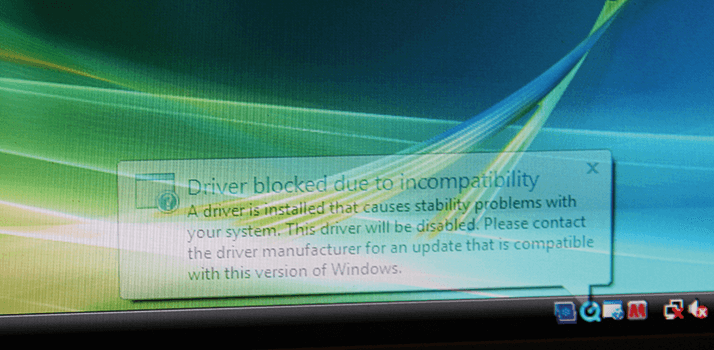

That’s not as simple as it sounds – sometimes you have no choice in the matter. Many medical device and instrument manufacturers prohibit the installation of antivirus software on their products, let alone upgrading Windows XP. Either they fear that something might break in the process, or they have concerns (particularly in the USA) that revising the software might mean that the entire system needs to be recertified to stringent regulatory standards. The fact is that most medical device instrument manufacturers aren’t massive corporations with a large number of programmers that can update – or even test – device drivers (the interface between the operating system and the added bit of hardware) for older instruments whenever a new version of Windows comes out (Figure 2), let alone a service pack or security update. It’s almost a form of superstition – during the commissioning of the instrument, the installation engineer hands it over to you to use, with the warning: it works now, don’t change anything! In an ideal world, manufacturers should build in security updates into the costs of the instrument, but in the real world, this doesn’t always happen.

Tinkerers rejoice: this doesn’t mean that the user can’t try upgrading their version of Windows at their own risk – but in many cases, risking downtime with a practice-critical instrument or device would be pretty irresponsible. Ironically, given its unpopularity, Windows Vista would have been the safest bet – its device driver model is similar to Windows XP’s (Windows 7 added additional layers of security – device signing – that can cause problems). Sadly Vista doesn’t have long to live: Microsoft’s “Extended Support” period expires on 4 November, 2017. Windows 7 does have one trick up its sleeve: Windows XP mode (actually, Windows 8 and 8.1 can do this too if you know how: bit.ly/XPmode8). It enables you to run a copy of Windows XP in a virtual machine (bit.ly/XPmodeVM). It’s not likely to help with medical devices, but it could help you get a new PC to run software that won’t run on later versions of Windows. Internet Explorer 8 is one such example – launched in 2008, even today one PC in five runs this version of the web browser. The reason why: many bespoke web applications – from appointment booking to electronic healthcare record systems – are broken by changes made in Internet Explorer 9.

Can you survive with XP?

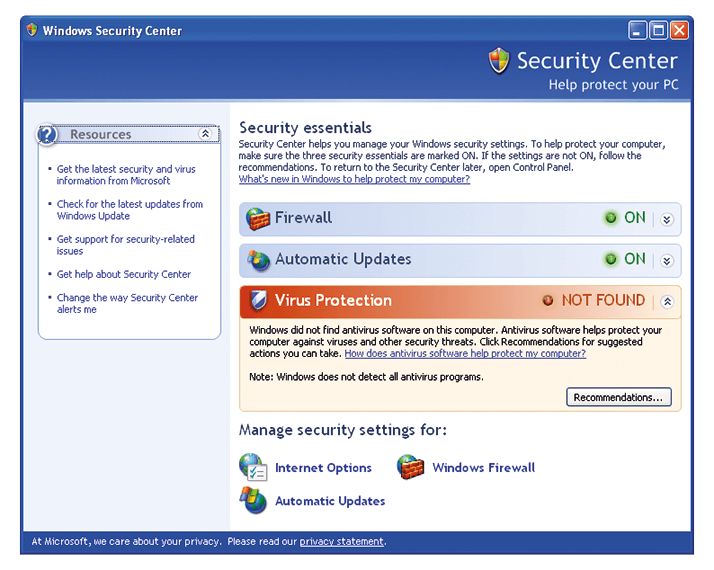

Possibly. Windows XP does have some safety features like a firewall (Figure 3) that can block incoming traffic from the internet (but not internal networks – people like to be able to see their servers and printers), and antivirus products are still made for the operating system (although whether you’re allowed to install them is another matter). The problem is that Windows XP’s firewall isn’t perfect, and there are any number of other ways for malware to be installed on a PC; visiting a compromised website, opening a nefarious email attachment – even infected PCs or laptops can spread viruses to vulnerable computers on internal networks.

You can maximize the chances of keeping your Windows XP-based PC secure by curtailing its connectivity: keeping it off the internet, potentially even the intranet, and as the Stuxnet case has shown, prohibiting the use of removable media. Unfortunately, that’s not very useful – in most cases, people will want to move data on and off these PCs, be it images, patient records, or datasets for analysis. The reality is that they will be used, they will be vulnerable, and they are likely to be infected with computer viruses or malware, hence headlines like “Computer Viruses Are ‘Rampant’ on Medical Devices in Hospitals” (bit.ly/rampantviri). Whether or not that interferes with the function of the PC is another matter, and clearly using an infected PC is not an ideal situation particularly if patient safety is at stake – but some will have the philosophy that if it works, it works, and if antivirus software can’t be installed… how will people know if there’s malware on the computer in the first place? The PC is slow? It’s old! PCs from the Windows XP era are starting to get old – parts fail, and even eventually the computers will be scrapped. However, when that PC is fundamentally required to run an expensive instrument, and you can almost certainly get the parts you need inexpensively from eBay… it’s more likely that if the instrument still does the job it needs to do, then the PC will be repaired rather than the whole system (PC and instrument) being replaced. PCs running Windows XP are a security worry with a long tail – just be aware of the risks associated with using them.

Pete Williams is an independent IT security consultant based in Cheshire, England, UK.