This is the first in a sub-series of famous one-eyed military leaders.

The loss of an eye is a highly unfavorable outcome in ophthalmology because it affects stereopsis, visual field, and overall quality of life. So it is perhaps surprising to find that many of history’s most celebrated military commanders had monocular vision – typically the result of trauma.

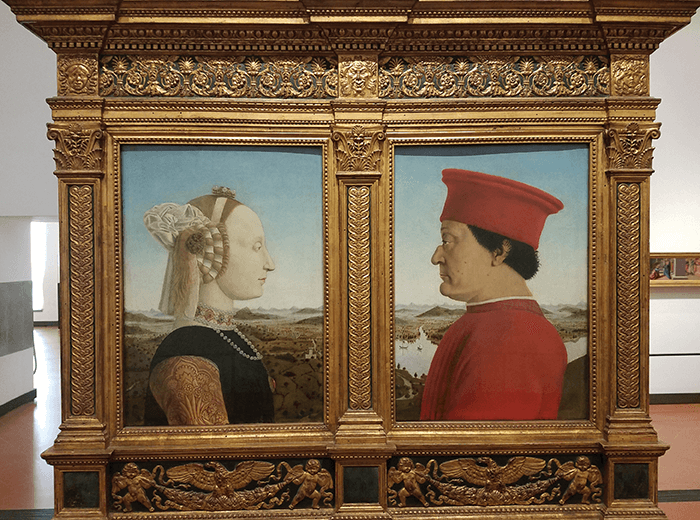

Federico da Montefeltro was born in 1422 and served as the Duke of Urbino from 1474 until his death in 1482. As a condottiero (leader of a mercenary army), he amassed great wealth through repeated military triumphs, which he then spent lavishly as a great patron of the arts, assembling a magnificent library in the Palazzo Ducale. Today, he is probably best remembered as the subject – along with his wife, Battista Sforza – of a famous painting by Piero della Francesca entitled “Portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Urbino,” which resides in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence and is shown in Figure 1.

The piece is notable for several reasons. The Duchess is depicted with a very high brow (an ideal at that time) and very pale skin. The light complexion was not only considered beautiful, but also reflected the fact that she died before the painting was completed. The Duke, in contrast, is depicted with a darker complexion – alongside multiple skin lesions, especially on the cheeks in a “warts and all” fashion, suggesting that this is how he really looked, rather than an idealized version. Further, there is an odd shape to his nose, with what seems to be missing tissue superiorly. Notably, the composition not only presented the couple as though they were staring into each other’s eyes, but it also had the benefit of capturing the Duke’s “better” side. He had no right eye.

Frederico is known to have suffered an eye injury in 1450 during a joust. Jousting-related eye injuries, while unusual, were occasionally reported; perhaps the most famous and historically significant was the injury to the French King Henri II, which ultimately proved fatal (1). What is unknown, and probably lost to history, is how the Duke’s nose came to obtain its distinctive shape. It may have been injured at the same time as his eye; however, a more intriguing hypothesis is that the Duke requested nasal surgery to somehow compensate for his lost eye. This theory has been proposed repeatedly by both lay historians and physicians (2). And since we cannot know for certain whether or not the surgery actually happened, a more interesting question is: Would it have helped?

Many individuals will find that, if they close one eye, an inferonasal visual field defect may be detected, especially with the eye turned nasally. The effect might be enhanced when one considers the eye motion visual field (EMVF) or “maximum field of vision,” which includes the additional visual field gained with eye movement. A study of normal binocular volunteers reported that mean EMVF measured 37 percent larger than standard binocular visual field measured without eye movement. In addition, EMVF increased with higher exophthalmometry measurements, demonstrating that facial anatomic variation can impact peripheral vision (3).

It is therefore possible that the removal of part of the Duke’s nose may have allowed expansion of the EMVF of his remaining left eye – comparable to what might result if the eye could have been made more proptotic. Of course, the additional EMVF would have come at the cost of disfiguring surgery in an era prior to the introduction of anesthesia, antimicrobials, or antisepsis.

References

- JG Ravin, “Lethal ocular injuries,” J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus, 17, 53 (1980). PMID: 6988566.

- SG Schwartz et al., “The monocular Duke of Urbino,” Ophthalmol Eye Dis, 8(Suppl 1), 15 (2016). PMID: 27980441.

- E Denion et al., “Eye motion increases temporal visual field extent,” Acta Ophthalmol, 92, e200 (2014). PMID: 23586899.