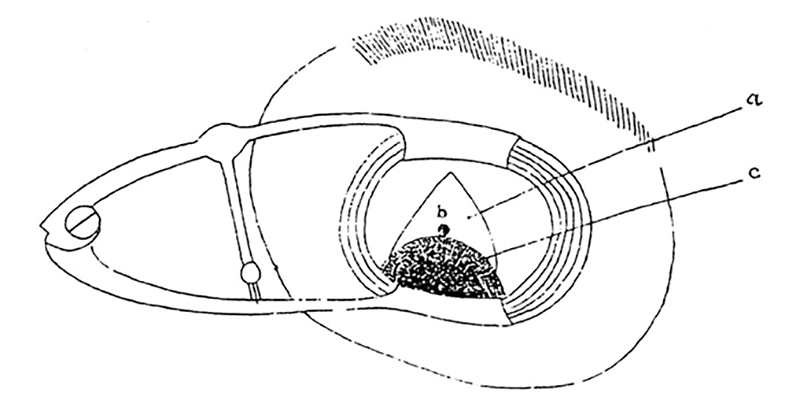

Figure 1. Elliot trephine procedure for glaucoma (1909). a. Exposed scleral surface, b. trephine hole, and c. = conjunctival flap. (Credit: Image supplied by authors)

As we reviewed in Part 1 of our History of Glaucoma, since antiquity the term glaucoma has described ophthalmic disorders with a light or bright pupil. Since the early 1700s, the term has been specifically related to angle-closure glaucoma, which sometimes produces a bright green or gray pupil – from corneal edema and from the mid-dilated pupil exposing a white or opalescent cataract.

A pressure-induced optic neuropathy (1850–1870)

With Helmholtz’s ophthalmoscope of 1850, observers noted an excavated optic neuropathy in the classic (angle-closure) glaucoma with a green pupil. The excavation of the nerve suggested that pressure was a defining characteristic of the disorder. In 1857, von Graefe noted the therapeutic benefit of iridectomy for angle-closure glaucoma. The excavated optic neuropathy was also seen in quiet eyes with a normal external appearance. In 1861, Donders noted elevated intraocular pressure in these quiet eyes with optic nerve excavation, and termed the condition “glaucoma simplex.” At the time, intraocular pressure was typically recorded using palpation with the finger, though Graefe and others experimented with tonometers from 1862 onward. Thus, in this period, all pressure-induced excavated optic neuropathies were considered glaucoma.

Angle-closure mechanism elucidated (1870–1939)

In the 1870s, Theodor Leber worked out the pathway for aqueous circulation, with its outflow through the anterior chamber “filtration angle.” The anteriorly bowed iris was understood to be blocking aqueous outflow. Glaucoma came to be seen as elevated intraocular pressure resulting not from excess secretion, but rather from inadequate aqueous outflow. Miotic therapy was introduced (1876), to pull the iris away from the angle. A broad peripheral iridectomy was understood to be removing iris tissue that had been obstructing aqueous outflow at the angle. Anterior sclerotomies were termed filtration surgeries, as the surgeons sought to simulate the natural outflow pathways.

This advance in the understanding of angle-closure glaucoma was a setback for the glaucoma simplex concept. Angle closure was frequently presumed to be the cause of all glaucoma. Most cases of glaucoma would have some degree of positive symptoms, such as pain, haloes, or injection.

Open-angle glaucoma elucidated (1940s onward)

Schiotz tonometry (1905) and gonioscopy were described early in the 20th century. In the 1940s, gonioscopy was used to classify glaucoma as open- or narrow-angle. Previously, open-angle cases would have presented at an end stage. The discovery of open-angle glaucoma led to identification of glaucoma cases and suspects through community screening programs, beginning in the 1940s. By the 1980s, all adults were advised to visit an eye specialist to rule out glaucoma.

Important 20th century therapies for glaucoma included the Elliot trephine (1909, see Figure 1), acetazolamide (1954), trabeculectomy (1968), laser iridotomy (1976), timolol (1978), argon laser trabeculoplasty (1979), apraclonidine (1987), dorzolamide (1995), and latanoprost (1996).

Further reading

CT Leffler et al., “What was glaucoma called before the 20th century?” Ophthalmology and Eye Diseases, 7, 21 (2015). PMID: 26483611.

CT Leffler, “Glaucoma: A Pressure-Induced Optic Neuropathy (1850-1870),” in Leffler (ed.), The History of Glaucoma, 263, Wayenborgh: 2020.

CT Leffler, “Angle Closure Glaucoma since 1871,” in The History of Glaucoma, 309.

CT Leffler, “Open Angle Glaucoma in the Twentieth Century,” in The History of Glaucoma, 431.

R Razeghinejad et al., “The History of Glaucoma Surgery and Laser Treatment,” in The History of Glaucoma, 513.

T Realini, E DeVience, “The History of Glaucoma Medications,” in The History of Glaucoma, 475.