This is the second in a sub-series of famous one-eyed military leaders. The first article featured the Duke of Urbino.

The loss of an eye is a highly unfavorable outcome in ophthalmology because it affects stereopsis, visual field, and overall quality of life. So, it is perhaps surprising to find that some of history’s most celebrated military commanders had monocular vision – typically the result of trauma.

Horatio Nelson (1758–1805) is probably the most celebrated naval commander in history. His most famous victory, which came at the Battle of Trafalgar, was also his last. There, the British Royal Navy defeated the larger combined French and Spanish fleet, preventing a planned invasion of England from Napoleon’s forces. Just prior to hostilities, Nelson sent the famous signal to the fleet: “England expects every man will do his duty.” Nelson was killed in action shortly thereafter, and is commemorated at Trafalgar Square in London.

Nelson sustained many injuries during his career, including the loss of his right arm at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1797. Additionally, he is reported to have lost vision in his right eye due to artillery fire at the Siege of Calvi in 1794 – three years prior to the arm injury.

Nelson wrote and spoke frequently of his eye injury, and he appears to have made the most of his monocular status. At Copenhagen in 1801, Vice-Admiral Hyde Parker ordered all ships to retreat. In response, Nelson held his telescope in front of his “blind” eye and remarked, “I really do not see the signal.” Defying Parker’s order, Nelson attacked and won the battle. Parker was subsequently recalled to England, and Nelson was promoted in his stead. Some say this anecdote popularized the expression “to turn a blind eye.”

Despite the injured eye being a memorable detail – one he often spoke of – and despite the stories that incorporated it, historians question the reality.

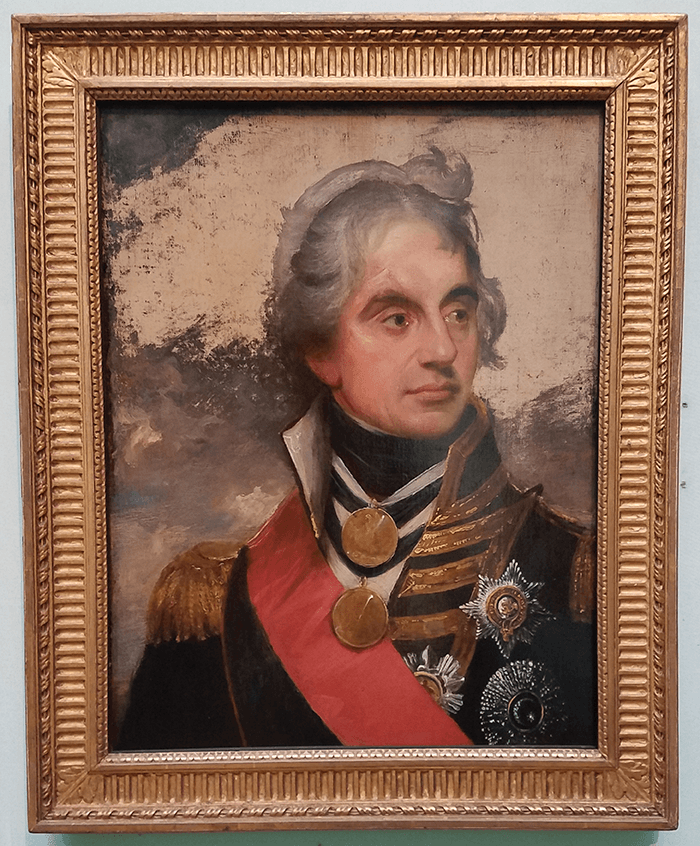

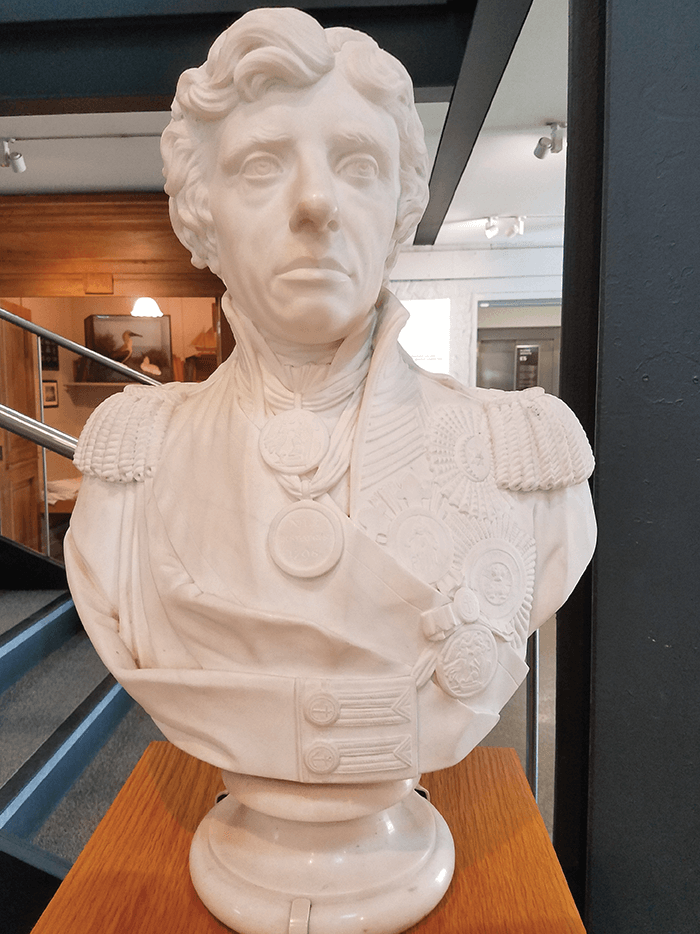

Outlandish? Well, Nelson’s damaged eye may indeed have been fictitious (1). The eye injury was not included in the official reports filed after the Siege of Calvi, where it would have occurred. Nelson was awarded a pension due to the arm injury, which occurred after the eye injury; at this time a blinding eye injury would have been enough to qualify for the pension itself. Perhaps most compelling, sculptures (Figure 1) and paintings (Figure 2) of Nelson generally feature an apparently normal right eye, although some do depict a scar over the right eyebrow. In general, portraits of other monocular military commanders acknowledge the eye injury in some way – or depict the subject from the side with the uninjured eye, such as the famous painting of the Duke of Urbino in Florence.

It is certainly possible that Nelson suffered a blinding injury that left him with a normal-appearing and non-strabismic right eye; traumatic optic neuropathy, choroidal rupture, or retinal detachment could all have been responsible. But we feel it is all too easy to imagine the flamboyant Nelson exploiting a minor eye injury to burnish his already fearsome reputation.

References

- SG Schwartz et al., “Famous monocular warriors.” Hist Ophthal Intern, 2, 161 (2018).