At the start of my ophthalmic career, I didn’t plan to get involved in sports vision. I was never a huge sports fan, and I’m not very good at sports myself. Of course, growing up in the US, you are never far away from a game (I was even present at the last game at the original Yankee Stadium), but I wasn’t a sports fanatic.

I did my ophthalmic training at the George Washington University in Washington, DC, and I went on to do a Pediatric Ophthalmology fellowship at UCLA’s Jules Stein Eye Institute in Los Angeles, California, US. Our program director and Chief of Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Arthur Rosenbaum, wanted all fellows to pick a project to work on. He mentioned a project that a previous fellow had started, which involved working with the Los Angeles Dodgers, looking at the baseball players’ vision. It sounded interesting, but I really wanted to pursue my own project, and not finish someone else’s, and I took it on the condition that I would be in charge and would make decisions on subsequent publications. Rosenbaum agreed, and that was the beginning of my career in sports and performance vision!

Working with LA Dodgers

As part of my project, I saw the Dodgers annually for about 18 years (or you could count it in seasons), starting in 1993, and only stopped working with them following the move of their practice location from Vero Beach, Florida, to Camelback Ranch-Glendale, Arizona. Even when I lived abroad, they would still bring me back every spring to carry on the work. Based on the research my team conducted while working with the Dodgers, we published our first paper in sports vision (1), which, I believe, was also the first paper on sports and performance vision published in any major ophthalmic journal. At that time, most ophthalmologists weren’t very positive about working on athlete’s vision, considering it to be the domain of optometrists and vision therapists, with no solid science behind it. But, as I became really interested in understanding how athletes’ visual systems differ from those of the general public, that didn’t stop me.

I was never particularly interested in the surgical aspects of ophthalmology, even though I performed Strabismus surgeries for 25 years. Instead, I’ve always been trying to find out more about how our brains use vision to make decisions that translate into actions. Over the years, attitudes of the ophthalmic community have changed – partly as a result of the refractive surgery boom – and sports vision has become a more popular topic among ophthalmologists, bringing more eyecare professionals to the field. Several good evidence-based publications on this topic have also changed the minds of many ophthalmologists and got them interested in this field, and in optimizing people’s vision and performance even in the absence of ocular pathologies.

Promoting sports vision

At the start of my sports vision career, eye care professionals working with sports teams and athletes weren’t paid beyond out-of-pocket expenses; our time wasn’t compensated, so I was doing this work (which involved conducting research and writing publications) on top of a busy pediatric ophthalmology and Strabismus practice, working seven days a week. Slowly, this changed, and as I began to get paid for my sports vision work, I could devote around half of my working time to it, with the other half still spent at my pediatric practice. Now, while I still see my young patients, most of my week is spent on sports vision science. Some of this work takes place at my New York City office, but most of it involves working directly with teams at different locations around the world.

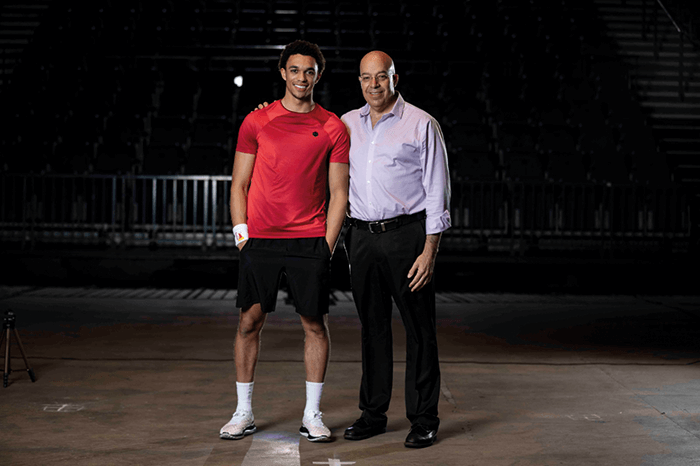

Many athletes and teams reach out to me directly, but I also proactively contact some big names and teams, like those in the English Premier League. It still surprises me how many big teams with huge budgets don’t even consider evaluating players’ vision as an important aspect of their performance. This is why the highly publicized project I worked on with Trent Alexander-Arnold from Liverpool FC in the UK was so important – it has opened people’s eyes to the potential of improving sportspeople’s visual performance and – in turn – their results. I traveled to Liverpool on two occasions, to test and to train Alexander-Arnold. This work was documented in the Red Bull movie available online (titled “Trent’s Vision”), documenting work we did together, the training Alexander-Arnold completed, and how his results improved. I have also published a film on my sports vision YouTube channel analyzing how aspects we worked on together impacted a later Liverpool FC game.

I have seen a whole spectrum of team management approaches, from extremely old fashioned to very forward-looking. I tend to work with teams taking the latter approach, as they aim to look at an array of tools, they can leverage to maximize performance. These include psychological aspects, sleep science, nutrition, and – of course – vision. Appreciation of the human body built from many different systems, and getting different professionals in all these areas to work with each other is crucial to improving performance and results. These days, the science behind these processes and interactions is well documented, so those in charge of improving athletes’ performance ought to be well aware of it.

Helping hands

When I go to work with a sports team, we usually have between 100 and 150 people to screen in a few days, so I often ask for help, often locally to where the team is based. Ophthalmologists appreciate the idea of working with a professional team and mixing with athletes. I also have great contacts who are always happy to exchange thoughts with me, and these include David B. Granet, Professor of Ophthalmology and Pediatrics at the Shiley Eye Institute of University of California in San Diego, and Bruce Mitchel Zagelbaum who practices in Manhasset, New York.

I hugely value relationships with researchers, such as Lawrence Gregory Appelbaum from the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California in San Diego, with whom I have just published an editorial in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience (2). In Europe, I work closely with Michel Guillon who practices at the Ocular Technology Group in London, UK. I have loved learning from researchers such as the late Richard Masland, Former Distinguished David Glendenning Cogan Professor of Ophthalmology and Neurobiology, and Jeremy M. Wolfe, Professor of Ophthalmology and Radiology at the Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, US, with focus on retina functions and visual perceptions, respectively.

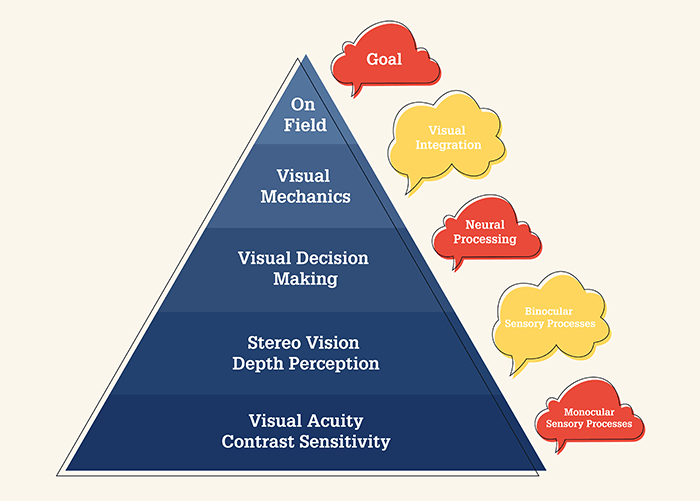

The sports vision pyramid

I have created a framework to understand the role of all vision interventions – testing, training, and more – and how they can all be used to improve performance. I have called it the sports vision pyramid, as it has a very strong base, and tapers to a point at the top. This pyramid has five levels, and if they are not all laid out in the correct order, and the bottom functions are not optimized well enough, the whole structure won’t be stable. As each of the levels is improved individually and in order, the top of the pyramid – field performance – will also improve.

At the bottom of the pyramid are the monocular visual functions: visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and ability to see things at all distances that appear for a short time. This is something that each eye can do by itself, and that’s why we test each eye separately, using a test (see below), showing the athlete targets from around 13 feet away, for a short time, and we evaluate the results. If the visual acuity isn’t what it needs to be, it can be addressed with training, with contact lenses or spectacles, or appropriate surgical procedures, while contrast sensitivity issues can be addressed with tinted lenses, for example. The next level is stereo vision – looking at how both eyes work together to create depth perception. This function is critical to know how far things away are. Then, it’s decision making based on visual information. Following that, it’s all about a visually guided motor action so that the body follows the decision.

In 2019, I published a paper with my colleagues showing how visual acuity – the bottom of the pyramid – impacts on the batting performance of baseball players (3). We also published a paper looking at the US Olympic team of 157 athletes taking part in the Beijing Olympics in 2008, and we demonstrated different visual functions of athletes representing different sports (4), but in any case, if you optimize each of the pyramid levels, the overall performance will improve.

Tests and interventions

Having abandoned the Snellen chart, which I deem wholly inadequate, I have worked with Alcon to develop a test – called the adaptive visual performance testing system – that is now used in ophthalmic drug testing, sports vision, military education, and other high-performance areas. It uses small targets shown to the patient for short amounts of time (such as 300-800 milliseconds) to reflect real-world scenarios. The test has been shown to correlate to performance in the field (3).

When talking about refractive interventions, it’s important to realize that 20/20 vision is a very weak standard in everyday life, but especially in sports, so refractive experts have to aim for much more. For young athletes, we aim to achieve 20/12, perhaps 20/15. Some of them achieve 20/08, which is typically considered to be the limit of human vision. Also, for athletes, small refractive errors can make a really big difference.

We have a whole host of interventions available beyond refraction, including games, augmented reality, virtual reality, and various applications available on tablets or computers.

Results

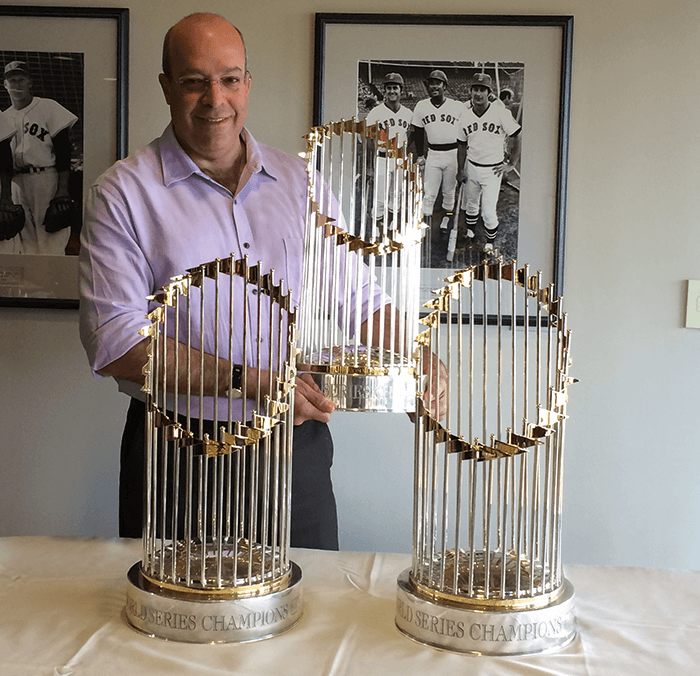

In 2004, I worked with a Dominican-American baseball outfielder, Manny Ramirez, who played in Major League Baseball for 19 seasons. My team developed a training scheme that helped him with his hand-eye coordination and decision-making. That year, he became the Most Valuable Player at the World Series, and he used our training as a warm-up before every game for the rest of his professional career.

In 2013, I worked with Stephen Drew, a Boston Red Sox infielder. We selected contact lenses with a small refractive correction for him and straight away he helped seal the World Series for the team.

I can confidently say that there’s no other ophthalmologist who has worked with as many champions among athletes and teams as I have, and I have around 10 championship rings to prove it.

Future directions

I work with baseball teams and players a lot, and I don’t have much capacity for additional work in the baseball field, but I would like to make my sports work an all-year-round occupation, rather than just seasonal. This is why I have been looking at professional soccer teams to work with, and I would like to do more work with the Premier League and Champions League teams, other European league teams as well as additional NBA, NHL, or NFL teams. That’s where the top players, with the top performing visual systems are! Every day, we are learning new things about the visual system, and it is fascinating to see how much we can learn from those at the top of the scale.

I have always been attracted to solving problems in ophthalmology that didn’t have very clear solutions – like Strabismus surgeries. I enjoy looking at new directions and coming up with fresh ideas to give an edge to the teams and athletes I work with. The more education on sports vision there is, the more people will reach out to specialists to help them get the vision to achieve their goals. This, in turn, will result in more investment from corporate entities for research to build an even bigger evidence base for sports vision. Sports and performance vision is a great field for those who don’t want to follow existing formulas in ophthalmology but want to have an opportunity to come up with new solutions. Let’s keep this field a true scientific discipline, based on solid research, with statistical data from randomized, double-blind and prospective studies. Scientific rigor and high scrutiny really matter in this field!

I have watched the field of sports and performance vision develop greatly, bridging ophthalmology and optometry, as well as vision research, to the benefit of teams, athletes, and everyone else – as everyone can all use the testing and training methods developed for the highest-performing humans. I share a lot of my knowledge and expertise on my YouTube channel in video presentations and TED talks, so it is available for everyone to learn from.

Hero and Teaser Credit: People images sourced from Shutterstock.com

References

- DM Laby et al., “The visual function of professional baseball players,” Am J Ophthalmol, 122, 476 (1996). PMID: 8862043.

- DM Laby et al., “Editorial: Neural mechanisms of perceptual-cognitive expertise in elite performers,” Front Hum Neurosci (2022). DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2022.923816.

- DM Laby et al., “The effect of visual function on the batting performance of professional baseball players,” Sci Rep, 9, 16847 (2019). PMID: 31728011.

- DM Laby et al., “The visual function of Olympic-level athletes – an initial report,” Eye Contact Lens, 37, 116 (2011). PMID: 21378577.