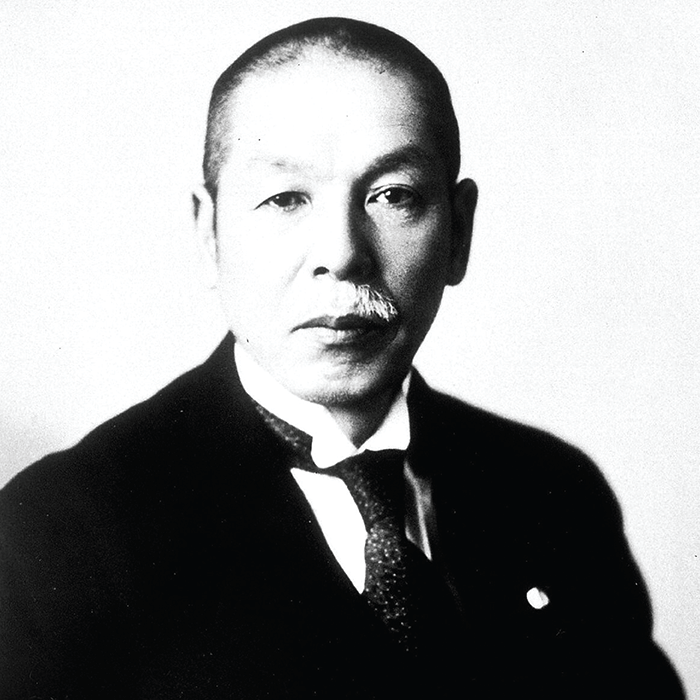

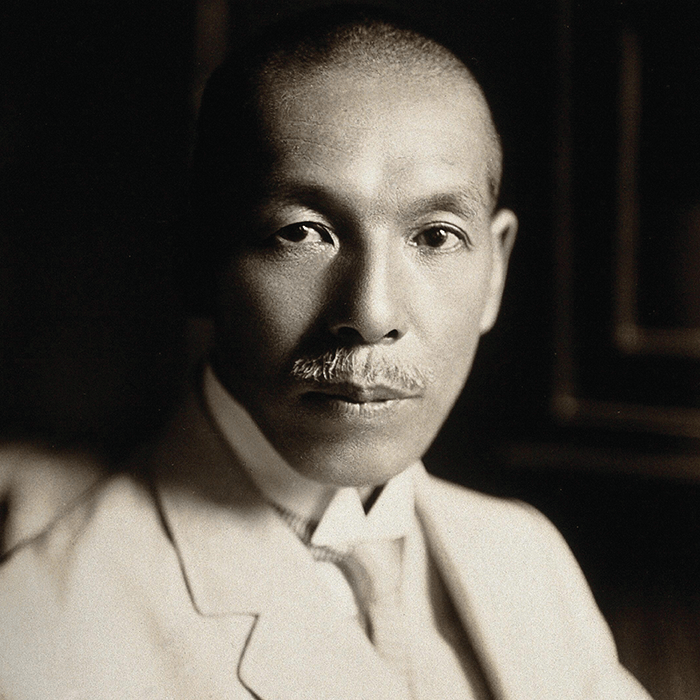

Color blindness is relatively common, affecting around one in 12 men and one in 200 women. Although it is generally not a cause for health concern, the inability to see certain colors can affect occupational pursuits. That’s where the star of this article comes in: Shinobu Ishihara, an ophthalmologist who developed the Ishihara color test in 1916 to identify color blindness in military personnel. Ishihara was born on September 25, 1879, in Tokyo, Japan. He graduated from the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1905 on a military scholarship and became a military physician until he completed his doctorate in ophthalmology in 1916. He then became full professor and Chief of the University Eye Clinic at Imperial University of Tokyo in 1922 and took on the role of Dean from 1927 until his retirement in 1940.

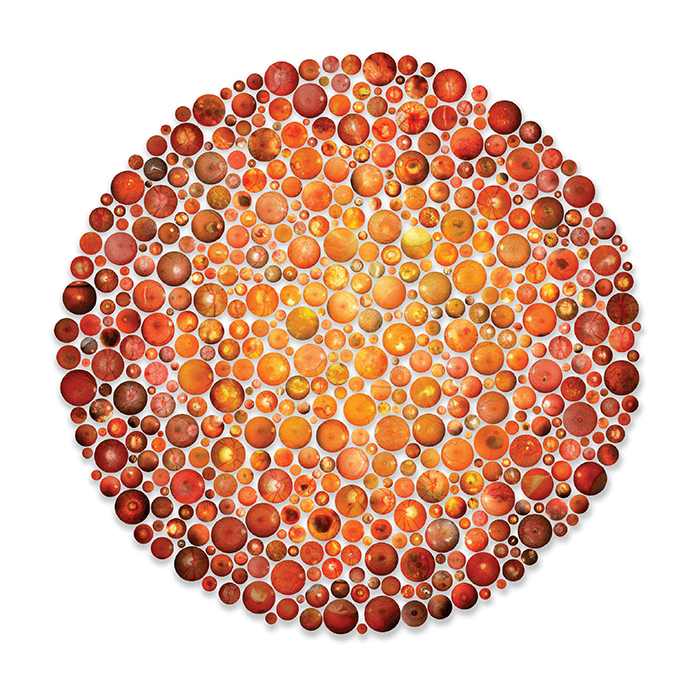

The test uses a series of plates – customarily 14, 24, or 38 – with closely packed colored dots of varying sizes forming a round depiction of a disguised number or character. The number of correct answers translates to a score that quantifies the severity of color blindness.

The original plates were all hand-painted in watercolor by Ishihara; the images depicted were of hiragana characters and later moved on to katakana (both Japanese phonetic lettering systems). When the plates were produced for international distribution, they moved to Arabic numerals. One of the issues with this test is that its success is very dependent on the quality of the colors on the plate, which can be affected by sunlight, wear and tear, and inconsistencies in the printing process. Although these issues haven’t gone away, the advent of a digital society and strong international printing capabilities have reduced the challenges faced in the early to mid-20th century.

The test is also limited to detecting red-green color blindness, but that hasn’t obstructed its popularity or usefulness. Even now, over a century after Ishihara painted his first plates, it is a quick and easy first test to detect defects in color vision that can be confirmed using more robust methods. It is also one of the most remarkable ways for people to understand how differently others may see the world.

The test is a fine legacy for an eye care professional, but it is far from Ishihara’s only impact on the medical community. He was so beloved by those he taught over the years that, upon his retirement, his students built him a cottage near the hot springs of the Izu Peninsula, west of Tokyo. There, he lived a modest life and worked as a doctor to the local community until his death on January 3, 1963.

Ishihara’s watercolor plates have inspired many artists, including Jon Brett, who has compiled images of different retinal diseases to form an Ishihara-style image.