- The EU is the second largest market in the world for medical devices, which in 2007 was worth more than €72.6 billion

- To be marketed in Europe, a device needs to meet safety requirements and attach a CE mark

- Depending on the type of product, the CE-marking process can range from self-certification to a rigorous external audit

- A regulatory plan will therefore help you anticipate the requirements and get your innovation its “passport” for European sales

There’s no denying that developing a new medical device is a huge undertaking. Once your device is created, has proven effective in clinical trials, and you’ve secured financing, you might be forgiven for feeling like the end is in sight – it’s not. To sell a product in any country, it must meet its regulatory standards. In Europe, this means the Conformité Européenne (CE) mark: all European Union (EU) member states and countries within the European Economic Area (EEA) require it. In 2007, sales of global medical devices and diagnostic products were €219 billion, with EU sales of €72.6 billion accounting for just over a third of that (1), making it the world’s second largest market for these products. Knowing when you need a CE mark and how to get one will help you enter this lucrative marketplace as quickly and easily as possible.

What is a CE mark?

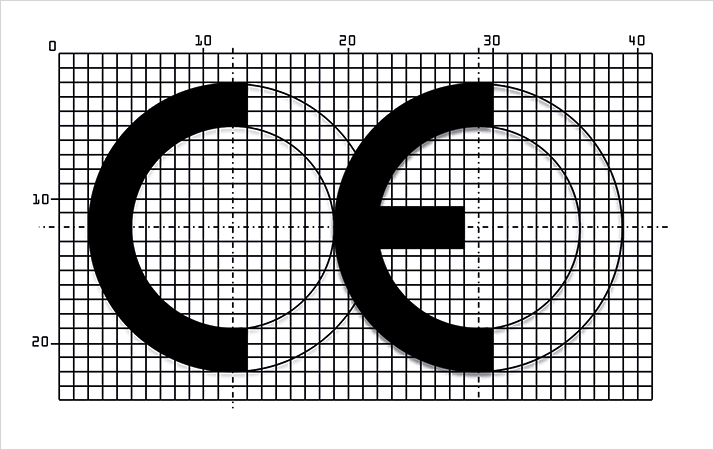

The mandatory CE label signifies conformity with European safety standards. It covers a wide range of items from medical devices to recreational sailboats, but excludes pharmaceuticals, foodstuffs and cosmetics. The mark itself consists of the standardized CE logo (Figure 1) and, for some devices, a four-digit code indicating the assessing organization. It’s displayed on packaging and instructions, and on the product itself wherever possible, but there are obvious exceptions; for instance, it would be inappropriate to place one on an intraocular lens.Like most items manufactured or sold in the EU, medical devices require a CE mark unless they are either samples, or custom-made devices for clinical trials. But the mark isn’t just accepted within the EU; the EEA, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), and Turkey also recognize it (2). Some countries within the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA) that have applied for EU membership are also adopting EU rulings into their legislation. Anything that’s made or sold within the EU that has the mark can be sold elsewhere, so it’s also a symbol seen around the world – and it’s why every iPhone sold around the globe has those two letters on the back of its case.

Six steps to certification

Manufacturers of many consumer goods can perform their own safety tests. But with medical devices, generally only Class I (low risk) devices that are non-sterile and have no measuring functions can be self-certified (see Table 1). For everything else, a notified body must be involved.There are several European directives that may apply to your invention. In order to get a CE mark, you need to establish a regulatory plan to guide you through the application process. There are six key steps to consider:

- Classification – Medical devices are classed by the type and duration of contact they have with the human body; understanding your device’s class allows you to plan for the assessment it will need. Intended use matters – the same thermometer can be used to measure liquid temperatures in a laboratory (not a medical device) and to measure the body temperature of a human being (making it a Class I measuring medical device).

- Directives – Which ones apply? Does your device need further testing or certification? (See MDD, AIMDD and IVDMD for more information).

- Do you need a notified body? – Chances are you do. The NANDO (New Approach Notified and Designated Organizations) Information System, found on the European Commission website, provides a searchable contact list of notified bodies. Any organization that can perform the relevant assessments may be used.

- Conformity – What assessments will your device need to pass? Does it meet the safety requirements in its current state? If there are any steps you need to take or changes to be made so that your device conforms properly, consider them before you begin the assessment process.

- Technical documentation – You can be asked to produce your device’s required documentation at any time. This might include instructions, lists of accessories, intended uses, component parts, details of manufacture, clinical trial data, results of safety tests, and more; full |details will be given by the directives relating to your product.

- Declare conformity and affix the CE mark – Once all tests have been carried out and documents compiled, you’ll need to draw up and sign a declaration of conformity. When applying the mark itself, remember that it must be clearly visible, legible, indelible, and standardized in size and shape. If a notified body was used, you must also include its identifying number.

How is CE marking enforced?

EU member states are required to carry out market surveillance and enforce legal safety requirements, but responsibility for ensuring compliance rests with the manufacturer – or, if applicable, authorized vendors or importers. It’s important to remember that you have to guarantee the safety of the device over its entire lifetime; any malfunctions, deteriorations or failures must be reported, and mistakes or inaccuracies must be labeled. Without satisfying all of the requirements, putting a CE mark on your product is a criminal offense. If a CE-marked device is noncompliant, authorities may allow you the opportunity to bring your device in line with the requirements, issue a fine, withdraw or recall the product, or in some cases even impose a custodial sentence.Worth the work?

Obtaining a CE mark may take a lot of effort, but it’s worth it. Once declared safe for market, your product can be sold throughout the EU without requiring additional approvals. That opens up the markets of at least 31 countries within the EEA, as well as any others who choose to accept the certification – that could be potentially huge. Sibylle Scholtz, Stefan Menzl, Carsten Rupprath and Myriam Becker are all authors of CE-Marking For Medical Devices: A guide through the maze of requirements in Europe (ISBN: 398139402X). In addition to writing the preface to the book, Gerd Auffarth is the director of the David J. Apple International Laboratory of Ocular Pathology and IVCRC as well as chairman of the Department of Ophthalmology, Ruprecht-Karls-University of Heidelberg, Germany.Glossary

Medical Device Article 1 of the MDD (see below) defines medical devices as: “All instruments, apparatus, appliances, software, substances or preparations made from substances or other articles, used alone or in combination, including the software intended by the manufacturer to be used specifically for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes and necessary for the device’s proper application, intended by the manufacturer to be used for human beings by virtue of their functions, for the purpose of: • Diagnosis, prevention, monitoring treatment or alleviation of disease• Diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation or compensation of injuries or handicaps

• Investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of the physical process

• Control of conception And which does not achieve its principal intended action in or on the human body by pharmacological, immunological or metabolic means, but which may be assisted in its function by such means.” Notified Body

An authorized third party that has been accredited by a member state of the EU to assess products in line with the requirements for CE marking. Medical Device Directive (MDD)

(93/42/EEC): Legal act of the EU that requires all member states to enforce standardized medical device (and marketing) legislation. In Vitro Medical Device Directive

(IVDMD) (98/79/EC): Concerns the marketing and regulation of in vitro medical devices – essentially, any device intended to be used in vitro for examining specimens derived from the human body, solely or principally for providing information on physiological or pathological state, congenital abnormality, safety and compatibility with potential recipients, or to monitor therapeutic measures. Active Implantable Medical Device

Directive (AIMDD) (90/385/EEC): Concerns the marketing and regulation of active and active implantable medical devices, i.e., any medical device (implantable or otherwise) that relies on electrical energy or a power source other than that directly generated by gravity or the human body.

References

- “European Commission, Public Health: Competitiveness – Facts and figures”, http://bit.ly/EUcompete “The ‘Blue Guide’ on the implementation of EU product rules”, (2014). http://bit.ly/blueguideEU The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), “Notified Bodies”, (2014). http://bit.ly/bodiesnotified, accessed December 15, 2014.