- Smartphones combine a lot of useful features for an assistive device: a light source, camera, display, speaker and internet connectivity

- Digital assistants (like Siri) plus specialist apps are helping blind and visually impaired people become even more independent

- From money-counting, color-coordinating your outfit, to summoning a sighted helper for a quick videoconference, it’s all available with an app

- The apps don’t stop there – they can provide patients, physicians, and families with access to invaluable networks and resources

Here’s an illustration of how much smartphones have become so intimately entwined with almost all aspects of our lives. Kate gets a WhatsApp message: “We’re all meeting up tonight at Tom’s Diner on Main Street 6.30 pm – see you there!” She picks an outfit, checks how to get there on an app, and as she’s about to leave, orders an Uber to get there. When she does, she checks out the menu – and sees her favorite burger and fries combination there, and orders it and some drinks. At the end of the evening, the partygoers split the bill (using a calculator app), and she orders an Uber home. But if I told you Kate is highly visually impaired, you’d find that the sequence of events – and smartphone usage – still holds true. Smartphones make for fantastically useful assistive devices. Most phones have a high resolution camera and display, a flash that can work as an illumination source, internet connectivity and the ability to run apps that exploit every one of these features. Let’s look at what’s available.

The fundamentals

Almost every smartphone, tablet and computer operating system comes with assistive technologies built in, with the simplest and most useful being screen readers. Apple’s devices that run iOS (the iPhone, iPad and iPod Touch) have VoiceOver, and devices that run Android have Google’s TalkBack. Most of today’s smartphones have dictation keyboards, meaning that users can give instruction to compose emails or run searches, for example. Then there’s smart digital assistants: Siri, Cortana, Alexa and Google Now. “Hey Siri. Compose an e-mail to…”, “OK Google. Navigate to…”, “Alexa, order an Uber to take me to…” Granted, they’re not perfect, but when they work, they can be very useful.Getting ready and getting there

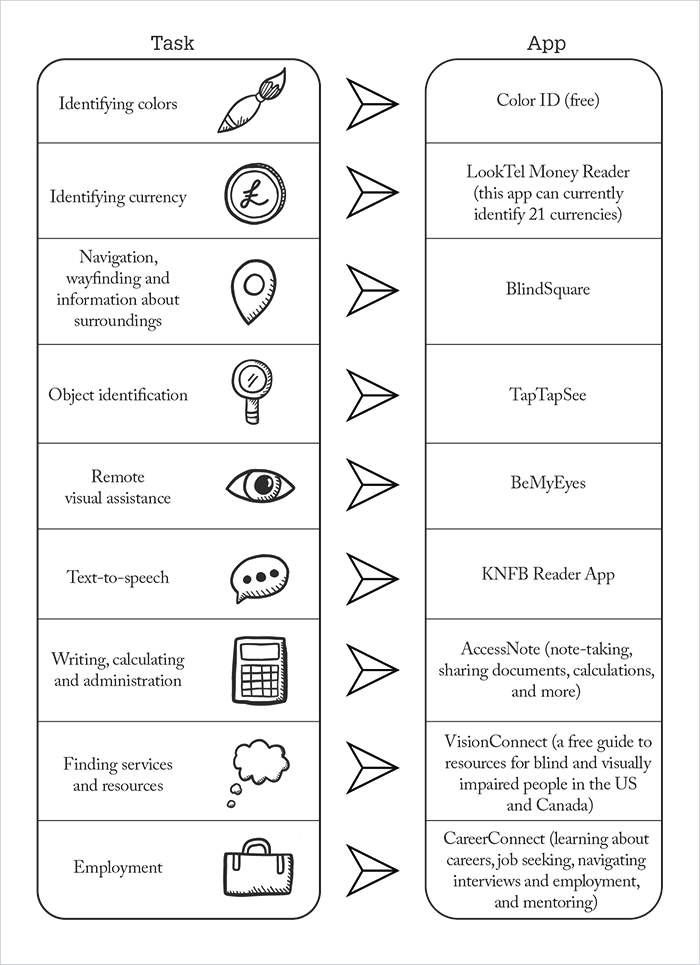

There are a number of apps specifically designed to increase the independence of people who are blind or visually impaired. If we go back to our example of Kate going out to a birthday gathering. What should she wear to the restaurant? Clothes that match – a blue blouse, with black jeans and a tan handbag. How can you do that? Download and run a color identifier app like Color ID, and it speaks aloud the colors that the camera sees. Kate’s now dressed for the event, but before heading out, she wants to check how much cash she has. She lives in the US, where all paper currency is the same size and shape. Is that a five or fifty-dollar bill in her purse? Unfortunately, she can’t always trust bartenders, waiting staff or cab drivers, so she finds apps like LookTel Money Reader invaluable for monitoring the cash she has in her pocket. Next, Kate need to find her way to Tom’s Diner. One very popular app that would help her here is BlindSquare, which allows users to find places of interest (e.g. hospitals, restaurants, shopping malls, etc.) and gives them turn-by-turn directions. But it looks like it’s a bit far to walk, so Kate asks Siri to summon an Uber. Kate’s arrived – but she’s the first there. Other than munching on a breadstick, there’s little else for her to do other than peruse the menu. She could open a text-to-speech app like KNFB Reader, but it turns out that BlindSquare already has the restaurant’s menu available within the app (and many thousands of other restaurants too), so she decides what to order in that app, then waits for the evening’s festivities to begin! To an onlooker, this is just yet another person constantly playing with their smartphone. But to Kate, this is something completely different: independence.Objects, text and remote assistance

Apps can help with more routine and mundane tasks – like finding things in the supermarket or turning on the heating. For object identification, there’s TapTapSee: if you don’t know what something is, this app can tell you. If you need to know if you’re picking up a bottle of shampoo or conditioner, you can take a picture with the app, and it’ll process the image and tell you what it is. Kate didn’t use the KNFB reader TTS app to read the restaurant’s menu in the example above, but these apps are incredibly useful. Say you’re staying in a hotel and find a Post-it note on your bed. Is it the breakfast menu? Information from housekeeping? Take a picture with the app, and it reads the text back to you. Another fantastic app is BeMyEyes. It uses your cellphone or tablet to connect you with a sighted person, and you can show them via your camera what you need help with – for example, you’re working to set the thermostat in your room, and all the buttons are the same size, shape, and color, making them hard to distinguish. The person can then assist you, saying “Okay, your temperature is set at 68°F, move your hand to the right – yes, that’s the one – tap that three times and your temperature will go down.”Working and networking

My employer, the American Foundation for the Blind, has created some apps of its own: AccessNote is a completely free productivity tool that enables the user to take notes, share documents, use a calculator, connect to their Dropbox, and more. Another is VisionConnect, which allows people in the US and Canada to share resources in their local communities, providing information on services such as computer training, Braille reading, guide dog training, and low vision services, all in a searchable directory. The information is up-to-date and pulls directly from our website (AFB.org) to quickly provide that information. This app is targeted towards physicians, professionals, and people with visual impairment. It can help provide information about eye conditions, tips on how to adapt your home for vision loss, and help to connect you to helpful services in your area.

Similarly, the AFB CareerConnect app is designed to aid people who are seeking employment, and teachers working with people with visual impairment. There are also job searching strategies and tools, answering questions like “how do I disclose my disability during the interview process?” It’s a great resource for people transitioning from high school or college to the world of work, and it’s also free. Although some of the apps I’ve mentioned here won’t be available in all countries, there are many, many more available (and in development). Resources like AccessWorld, AppleVis, and Top Tech Tidbits can all be useful sources of information for finding apps specific to your location and language – and if you aren’t sure, the best way to evaluate the usefulness of an app is to simply download it, and give it a go.

Assisting independence

These apps are just some of the ways in which new technologies are helping people with vision loss maintain their independence, find a job, and stay employed – and there are many more out there than I have mentioned here. Being aware of the technology available for patients who are blind or have vision loss, and introducing them, could help to improve their ability to navigate everyday tasks independently – and have a very positive impact on their quality of life.Lee Huffman is the Editor-in-Chief of AccessWorld, the American Foundation for the Blind’s monthly online magazine, which provides news and reviews of accessible technology used by blind and visually impaired people.