When was the last time you heard anyone say something positive about electronic health records (EHRs)? Many ophthalmologists and physicians are obliged to use them, and find them burdensome: both difficult to use and time consuming. These systems may hold the promise of revolutionizing patient care by reducing costs and increasing efficiency… but their implementation into clinics has been met with increased frustration and discontent. The users just aren’t seeing any of the benefits, and worryingly, many feel that they’ve negatively impacted patient care. But are ophthalmologists, and physicians, being blinded by the “good old” days of paper records and unable to see how EHRs could improve the day-to-day practice of medicine? Perhaps everyone needs to see the bigger picture. Remember the simulation game craze of the 1990s, which started with SimCity and included Theme Hospital? It’s now possible to move beyond gameplay scenarios and actually simulate the working of real hospitals and clinics – all thanks to the data collected by EHRs. The numbers of patients, waiting times, workflow, resource usage, even doctor and technician time utilization can all be modeled, and the resulting simulations could be used to virtually “stress test” new scenarios without inconveniencing or disrupting clinical workflow. This is hugely important in ophthalmology: anything that helps treat the increasing numbers of patients with age-related eye disease more effectively and efficiently with the same resources would be welcomed with open arms. Michael Chiang is an expert on this topic. Here, he shares his story on the EHR research conducted at his institute – and how they’ve used the technology to their advantage.

A brief history of EHRs

We are in the middle of a revolution – paper charts are being replaced by EHRs. Back in 2007, an AAO survey found that 12 percent of ophthalmologists were using EHRs (1). By 2011, two years after meaningful use legislation came into force, EHR use had leapt to 32 percent, with a further 15–31 percent in the process of implementing systems or planning to do so (2). The results were clear – EHR use had tripled in just a few years. Right now, around 65 or 70 percent of ophthalmologists use EHRs, and compared with 2007, this represents a huge shift in how they care for patients, document cases and spend their time. But what impact has this shift had on patient care? Between the two surveys in 2007 and 2011, ophthalmologists’ satisfaction with their EHRs lowered – as well as their perceptions on any beneficial effects in terms of productivity and costs (2). In 2014, around two-thirds of physicians were dissatisfied with their EHR functionality, and felt that their EHRs resulted in financial losses (3). And from my role as Chair of the AAO’s Information Technology Committee, during that time I was hearing these complaints first hand. As EHR adoption became more widespread, the numbers of criticisms about them rocketed. Paper records weren’t perfect, but they were fast, whereas EHRs took considerably more time for most people to complete because they require pointing a mouse, clicking and typing. With the shift to EHRs, many doctors were concerned that they were seeing fewer patients.Having my own concerns about the efficiency of the transition from paper records, I became interested in the effects of EHR implementation on ophthalmologists. To find out, I put my own institute – the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) – under the microscope.

Burden and volume

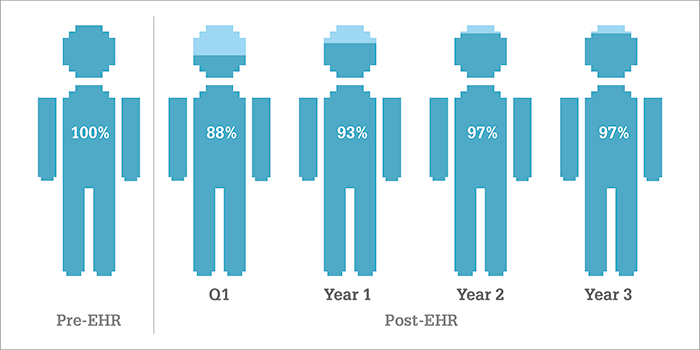

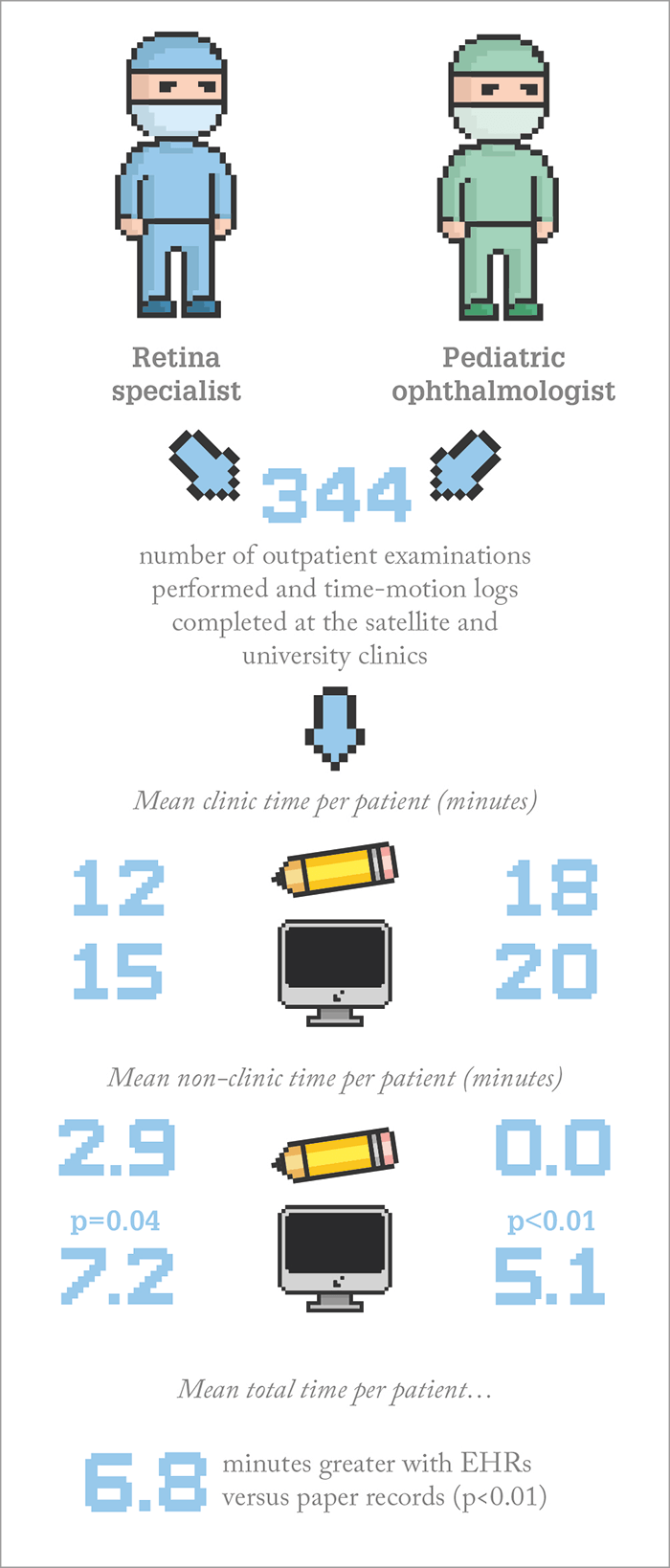

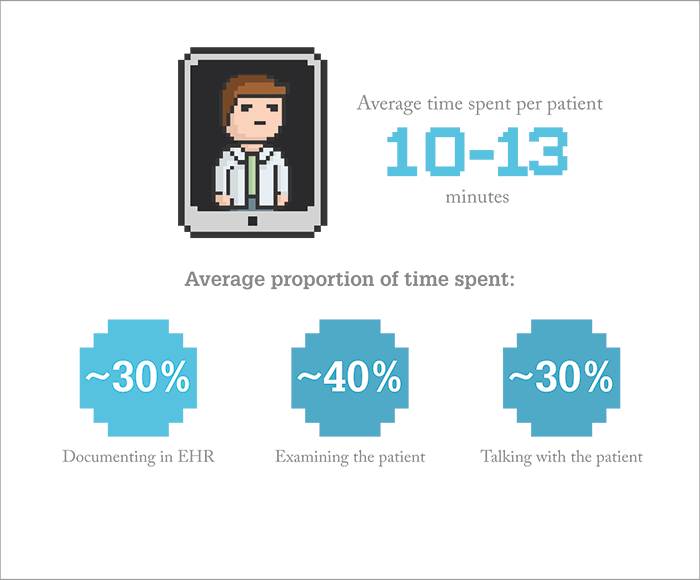

At OHSU, February 2006 marked the transition from traditional paper-based records to an institution-wide EHR, but in the first three years after implementation, clinical volume went down 3–7 percent – and stayed down at that level (Figure 1 (4)). Was this due to doctors taking longer to document in the EHR? Because no one had looked at how long it took to complete paper records, it was hard to tell. However, it so happened that we (myself and several colleagues from OHSU) were presented with an opportunity to compare EHRs with paper – two OHSU ophthalmologists were visiting patients at a University satellite clinic in rural Oregon that hadn’t yet implemented EHRs.By comparing data from logs completed at the satellite clinic (paper charting) versus data from the main clinic (EHR records), we found that they were spending almost seven extra minutes per patient with EHRs – a significant difference (Figure 2). Although we published this back in 2013 (4), it’s still some of the most detailed data available demonstrating that EHRs actually have a negative impact on ophthalmologists’ time – rather than relying on anecdotal evidence from physicians expressing their concerns at meetings or saying “I can’t talk to my patients anymore because I am typing all the time – I don’t have the same patient/doctor interaction.” But why was it taking doctors longer to document? To figure this out, we decided to perform a time-motion study to record what doctors were actually doing with the EHRs – and where the extra time may be going. We developed iPad apps to record the times taken for activities and trained observers to shadow five different ophthalmologists in the clinics at OHSU over a period of two years. What did we find? That the ophthalmologists spent an average of 10–13 minutes directly face-to-face with a patient, and almost 30 percent of this time was spent using the EHR (5) (Figure 3). So they weren’t getting a lot of time with patients, and of this time, a significant amount was actually interacting with a machine rather than directly with the patient. Talking informally with other doctors invoked some strong initial reactions: “That’s terrible – a third of my time is being taken and used for a machine!” But we hadn’t designed the study to say whether this time spent documenting during an exam was good or bad for quality of care: it could be argued either way because taking time to log data in preparation for the next visit has value. Regardless, with many physicians complaining “We’re spending all night charting and we never used to,” we decided to perform a timestamp analysis to see when doctors were completing their EHRs. To do this, we went into the audit log.

Looking for the silver lining

EHRs retain a wealth of information in their audit log because they record clicks, points and keystrokes. After validating that EHR timestamps were very close to the gold-standard of manual time-motion collection using the iPads – on average, around a minute apart – we analyzed the timestamp data to identify when our ophthalmologists were documenting, and for how long. There was certainly plenty of big data to play with – audit logs from five ophthalmologists equated to almost three million mouse clicks a year to analyze! Nevertheless, our analysis revealed that they spent around 10 minutes per patient using the EHR, and that over half of this EHR use was when the patient was in the office, over a quarter was within business hours but not when the patient was in the office, and the remainder was at nights and weekends (5), (6). So although the documentation times differed depending on the ophthalmologist and their role, when you consider the average ophthalmologist who spends 10 minutes per patient documenting 30 patients a day – that’s approximately five hours a day using the EHR. Whilst we can’t conclude from our results whether EHR use is detrimental or beneficial to patient care, it’s clear that completing EHR documentation takes a significant amount of time – and that we need to make these systems more user friendly and efficient. Until this happens, I think the “silver lining” is that the information they gather can be valuable for improving our practices. Many websites can deduce information about us, or provide recommendations to us, based on our click patterns, with a pretty high accuracy for what we may be interested in. A similar paradigm can be applied to EHR systems – we can use them to collect data on our workflow and practices, and we can use this to suggest improvements.Let’s use it to our advantage and…

All ophthalmologists – like every doctor – are under pressure to see more patients in less time, and are also being increasingly pushed for quality. Using multiple exam rooms is one of the ways we’ve adapted to this. Years ago, one doctor would use one room – and do everything by themselves. Now, we hire technicians and move between multiple rooms, but this comes with its own complications because patients and different personnel are also moving between the different rooms as patients need to be dilated, imaged, have their visual fields tested, and so on. It’s always been a challenge for me to try and understand the most efficient way of doing this, and this led me to wonder if we can design computer simulations to understand the optimal configuration of who goes where and when? How do we schedule our patients to optimize efficiency? Driven by this curiosity, we assembled a multidisciplinary team including informaticians, industrial engineers and hospital personnel to assess how we might use EHR data to develop simulation models to optimize and improve clinic workflow.…optimize workflow

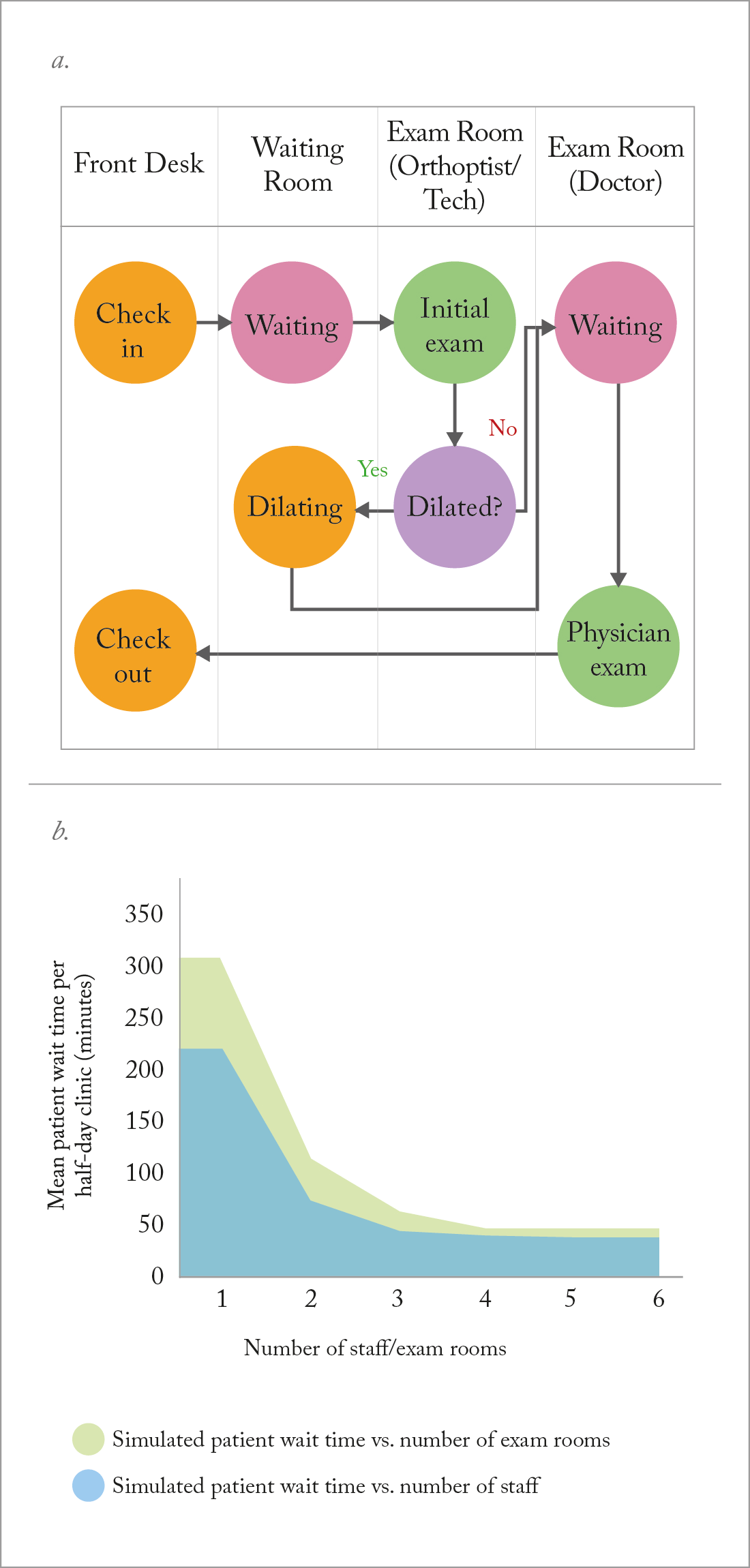

We’ve been able to show that EHR timestamp data can accurately capture how long every process in the patient’s clinic visit takes, from when they enter the clinic to when they leave, when they wait in the waiting room, when they get their eyes dilated – and so on. We’ve also been able to validate using these timestamps to represent clinical workflow, and with this information, we’ve built models of clinical workflow that can simulate and predict not only average waiting time, but also what the average clinic length is from start to finish (Figure 4a) (7). Most recently, we’ve been working on a computer simulation model built from two years of EHR timestamp data collected from four different ophthalmology clinics at OHSU (pediatric, comprehensive, glaucoma, cornea), and we’ve already determined some interesting insights (8). In terms of efficiency, I’d always wondered how many technicians an ophthalmologist should employ, and how many exam rooms they should use. Our computer models have suggested that after a certain point there’s no further benefit to efficiency because the doctor becomes the rate limiting step and causes a clinical bottleneck – a break-even point is reached (Figure 4b).

Furthermore, our models have suggested ways to improve scheduling strategy. Right now, patient scheduling can be random because it is based on patient availability or staff intuition, and at our clinic, we’d always scheduled more challenging patients at the beginning of the day based on the rationale that they would be seen sooner. But our simulation models showed that although clinic length might be reduced with this approach, average patient wait can be increased: the ophthalmologist isn’t seeing any patients at the beginning of the day whilst the technician is working with the more challenging patients, and these delays percolate throughout the entire clinic. Scheduling “longer exposure” patients requires a compromise between patient wait time and clinic length – according to the models, around 70 percent of the way through the day appears to be the ideal place to schedule these more challenging patient cases. Although we’ve needed to schedule well in advance, we’ve tried this strategy in our clinic and it seems to work. By implementing some of the schedules from our computer simulation models into the clinic, we have also been able to reduce mean waiting time from around 36 minutes to around 25 minutes per patient (p=0.03) (9). Our results are encouraging – but it’s only the beginning (see “What We Know”).

The road ahead – from foe to friend?

I’m sure that many reading this agree that EHRs need to be better – and may be frustrated by some of the impediments causing a roadblock to their improvement. A lot of EHRs are based on older technologies that are less flexible than modern ones and many systems look as if they were developed with little or no physician input. Another problem with EHRs is cost – the huge sums of money involved in implementing these systems means that hospitals can’t easily set up new systems. This is why this project, this concept of a secondary use of EHRs, really interests me. It has an operational component that resonates with all ophthalmologists and physicians in general – we all have our own stories that it speaks to. EHRs aren’t perfect, and the barriers to making better systems means we’re unlikely to see them improve in the immediate future. But if we can use the information from them to discover new things, find the most efficient ways of managing our patients and our workflow, and hopefully make our clinics run more smoothly, then this could be really valuable – EHRs could become a powerful tool for managing clinical workflow. We’re continuing our work at OHSU and hopefully one day this aspect of EHR-based simulation modeling will benefit many physicians, not just ophthalmologists. Michael Chiang is the Knowles Professor of Ophthalmology, Medical Informatics, and Clinical Epidemiology at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU), and leads the Oregon State Elks Center for Ophthalmic Informatics. Chiang would like to acknowledge his collaborators, which include Sarah Read-Brown, Michelle Hribar, Leah Reznik, Isaac Goldstein, Jessica Wallace and Thomas Yackel, all of OHSU.References

- MF Chiang et al., “Adoption and perceptions of electronic health record systems by ophthalmologists: an American Academy of Ophthalmology survey”, Ophthalmol, 115, 1591–1597 (2008). PMID: 18486218. MV Boland et al., “Adoption of electronic health records and preparations for demonstrating meaningful use: an American Academy of Ophthalmology survey”, Ophthalmol, 120, 1702–1710 (2013). PMID: 23806425. DR Verdon, “Medical Economics EHR survey probes physician angst about adoption, use of technology”, (2014). Available at: http://bit.ly/MedEconom. Accessed December 1, 2016. MF Chiang et al., “Evaluation of electronic health record implementation in ophthalmology at an academic medical center (an American Ophthalmological Society thesis)”, Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc, 111, 70–92 (2013). PMID: 24167326. MF Chiang et al., “Time requirements for pediatric ophthalmology documentation with electronic health records (EHRs): a time motion and big data study”, JAAPOS, 20, e2–e3 (2016). MF Chiang. “Time requirements for pediatric ophthalmology documentation with electronic health records: a time-motion and big data study”. Paper presented at the AAO Annual Symposium; Chicago, USA. MR Hribar et al., “Secondary use of EHR timestamp data: validation and application for workflow optimization”, AMIA Annu Symp Proc, eCollection 2015, 1909–1917 (2015). PMID: 26958290. MR Hribar. “Clinic Workflow Simulations using Secondary EHR Data”. Paper presented at the AMIA Annual Symposium; November 16, 2016; Chicago, USA. G Reznik et al., “Computer simulation models for optimizing clinical workflow in pediatric ophthalmology”, JAAPOS, 20, e22–e23 (2016).