It’s not hyperbole to consider Rob Johnston as one of the fathers of big data in eyecare. Along with his brother, David, he founded Medisoft. The structured, clear-minded, clinician-designed electronic medical record (EMR) system that they produced – and the data it holds – is certainly enabling ophthalmologists to gain great insight into the practice of their specialty. But, perhaps more importantly, it’s also perfect fodder for machine learning in medicine – a field led by ophthalmology, in large part thanks to Rob. But he wasn’t just the Clinical Director of Medisoft: he was a committed and caring vitreoretinal surgeon, an educator, a husband, a father, a manager, a mentor and a friend to many. He died last year, after a 12-year long fight against cancer. A year after his death, his brother, David Johnston, his former fellow Javier Zarranz-Ventura, and former colleague Adnan Tufail came together to discuss Rob, his life and work, and what he meant to them.

The Man

Javier Zarranz-Ventura (JZV): I went to Moorfields [from Spain] as a medical retina fellow, but I also wanted to do a vitreoretinal (VR) fellowship. One of my bosses there, Adnan, told me that a friend of his in Cheltenham also did lots of great research. It was Rob. I met him and we immediately got on – an instant link! I spent a year there, but from day one, he looked after me and my wife. My mother used to tell me that it’s normal to hear good and bad things about people – but there are a few exceptions, when you only hear good or bad things about somebody. With Rob, people only said good things. He looked after us so well. My wife, Paula, and I had planned to fly home for Christmas that year – we already had our flights booked – but when she came home with the staff rota, she had to cover Christmas Eve. As she would be in the hospital all day, she said it would be silly for me to stay. I mentioned to Rob during a coffee break how it was going to be kind of sad. He didn’t even think for a second about his reply: “Ask her to come over, ask her to come over!” I’ve worked with many people in many hospitals, and no matter how sociable you are, you connect better with some people than others – but to be in a foreign country and have someone ask your wife to spend Christmas Eve with their family? That’s a perfect example of who Rob was. My wife always says that the time spent in Rob’s house was the only good part of a terrible day. In hospital, it was a really rough day; people died, and she ended up finishing really late. When she finally arrived at Rob’s house, as he opened the door, his youngest son, Angus, who must have been 2 or 3 years at the time, ran over, said “hello”, grabbed her leg, brought her in – it was so lovely, it almost brought her to tears. She then had dinner with Rob and his family and it was such a lovely evening for her! That was Rob. He was generous, caring and he looked after his staff, family and friends. And it wasn’t just me, it was everyone; ask the people in Cheltenham. All the trainees, registrars and fellows were delighted with Rob because they were never left to fend for themselves; he was always there if they needed something – he would never say no to anybody who needed advice. He was always very approachable, he never ignored people or turned anyone down to make his own day easier. He was simply not like that, not even when it was really late and he needed to get home. The best thing? His style has rubbed off on me. He has influenced how I treat my own residents. If someone comes to me with even the most trivial thing, I’ll take a look. Why? At the back of my head, I hear Rob saying, “If you can do something to help someone, don’t turn them down.”AT: When Rob was a trainee in London and looking for his first consultant job, he broke up with his long-term girlfriend. He was single, and so wanted to get a job in London. When the Cheltenham job came up – the first consultant job he ever applied for – he had mixed feelings about it. He certainly wasn’t thinking, “‘Oh, I must go to Cheltenham’ – he thought everyone would be ‘very’ married; children, a dog, all that kind of stuff. But he got offered the job and took it, while thinking “Oh no!” However, he had only been in Cheltenham for a short time when he met Alice – a trainee anesthetist. She became his wife and the mother of his three children, so it all worked out really well in the end!

Cheltenham

Adnan Tufail (AT): When Rob took the VR Consultant job in Cheltenham, he could have taken any VR job in the country – but he’d worked there before, and everybody knew him. It was already a good department, but Rob definitely gave it a big boost. Cheltenham is a small place – but it’s one of the top units in the UK. Cheltenham was also the premier first VR fellowship in the UK for those coming from Australia – Moorfields will only take people who had done it for a year, and the recommended post is Cheltenham. There are huge numbers of Australians coming over here through word-of-mouth recommendations – it is probably the most popular starting fellowship in the country. JZV: I don’t know what the service was before him, but he was definitely one of the driving forces behind the training scheme, which was excellent. I’ve worked in many places and I have never seen a theatre or an intravitreal therapy unit that worked better than Rob’s, either in terms of patient flow or patient clinics. Of course, it’s also true that he had an army behind him, especially with the intravitreal therapy unit – but you need the right person to build that up. AT: It’s fair to say that Cheltenham was a good department with some very good senior people before Rob arrived; he wouldn’t have taken the job otherwise. Nevertheless, he set up the macular treatment service himself; he knew it would be the next big thing, so he thought quite seriously about how to make it as efficient as possible. He had optometrists and nurses seeing patients with multiple OCT machines, and so he had a much higher throughput per consultant or per ophthalmologist than most places; the patients got seen every four weeks, and that’s important, because if they don’t get seen every four weeks their sight can deteriorate. JZV: How the unit works is amazing… Remember the LUMINOUS study (1), which is directed to assess the use of ranibizumab in routine clinical care? Rob said, “OK, this is a real-life study, let’s do this!” Within a week, Cheltenham was one of the highest recruiting centers in the world.Chicken or egg?

AT: He had a good mind for process, which must have helped with building Medisoft. You need the data to be right… David Johnston (DJ): But it’s not just about the data, it’s also about understanding how the clinic works and how a patient flows through it. When designing the Medisoft ophthalmology EMR, Rob had to think about every step: arriving at reception, seeing a nurse, then having a series of diagnostic tests and then seeing an optometrist or doctor, for example. Rob was forced to think about processes from his experience as a trainee. So designing Medisoft’s ophthalmology EMR definitely helped him design an optimal care pathway for the macular treatment service at Cheltenham General Hospital.The Medisoft Story

Mark Hillen (MH): How did you go from an EMR system to being involved in the world of big data? DJ: To be honest, we didn’t have big data in mind when we started Medisoft; no one had even heard of the concept. I don’t remember the exact date, but it must have been in 1996 when we were both living in London: Rob was a trainee and I worked for a pharma company called Ipsen. I used to market a botulinum toxin product, Dysport, which was prescribed purely for blepharospasm and hemifacial spasm – both of which are treated by ophthalmologists. (This was a long time before this was used to smooth wrinkles!) I’d been doing that for five years, and by then I’d come to know probably half the consultant ophthalmologists in the UK. I’d visited nearly all the units and knew how selling into an NHS organization worked. But I’d grown bored of my job, so when Rob had the idea to create an ophthalmology medical records system, it was just perfect timing and I quit my job. The idea was interesting, but neither of us were techies at all (I’m still not) so we knew we’d need some help. Rob wrote a spec and I got a friend of mine in Leeds to write a very rudimentary demo program. I showed it to some of the ophthalmologists I’d met selling Dysport, and asked them if they’d buy the fully working system. The response: “Yes, definitely!” In early 1997, we formed the company. But the original objective was just to have a patient record system that permitted easy data collection and analysis of that data, including a good audit of outcomes. It’s not possible to do a comprehensive audit of all patients seen in an eye department by trawling through the paper notes. Rob’s vision was that if all the data is stored in the right way on a computer system, detailed comprehensive audits of the data will be possible at the click of a button. AT: But back then, audits were rudimentary even in the UK. Nevertheless, I think Rob and David could see the importance of looking at quality outcomes and how it would be vital in the future for all sorts of reasons. They recognized this very early on, before anyone else. It took a lot of courage to start that kind of project in the mid-1990s environment. DJ: That may be true! But I could see that the chances of me crawling to the top of the greasy pole in an established pharma company were even more remote, so I was dying to do something else! I deeply respected Rob and had complete faith that his idea would work. I knew he wouldn’t have considered starting the enterprise unless he was confident that it would work out in the long term. Of course, audits were paper-based at the time: crude and basic. To do an audit of cataract surgery, for example, you’d have to pick 100 patient notes randomly and then transcribe information from the notes into an Excel file... It was incredibly slow and painstaking manual work, prone to error, and then only sampled a small subset of all the patients seen. We knew that computerization would enable the audit to cover everybody, and that would be really powerful. So when we designed the system, we started by considering what you would need in the audit – that was the first thing we thought about. Then we designed the system around that; whereas most EMRs are just about collecting information, but not in a structured way. We designed a system where you could press a button and get your audit.Even now that EMRs have taken off in the US, most of them are essentially glorified billing systems. You’ll have paperless records, but you can’t extract and analyze the data because they were never designed to do that. To go back and redesign those kind of systems would be a nightmare. Rob did it better because he and the Medisoft team actually took into account what clinicians wanted to measure and designed the software with that in mind. We designed the first version for cataract surgery – a very sensible and pragmatic decision by Rob (a VR surgeon), as it’s the most commonly performed eye operation – the most common surgical procedure of any type in the world, I believe. It was only in the last three or four years that Medisoft developed a VR module, because Rob always looked at it from the point of view of hospital needs and customer needs. Cataracts came first, then it was glaucoma, and then medical retina. So, our first system was essentially a cataract surgery EMR system with a very good audit function. Once we’d got that into five NHS Trusts, the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOph) got to hear about it. They approached us to see if we could pool the data to do a study. That’s when we first did anything like ‘big data’. We approached these centers, and we got patient confidentiality approval from all the Caldicott Guardians at each Trust so we could extract anonymized data. JZV: It got published in Eye in 2005 (2), but I think it was 16,500 cataract operations. Compared to what we can do now, that’s nothing, but at the time it was a big deal. And it got this really amazing editorial, Rule Britannia, from a fine American epidemiologist who sang Rob’s praises (3).

Bigger data – and seeing more

DJ: Given such studies at that time, it really was revolutionary. It was still very early days for us – now we have over 80 Trusts using the system. In about 2006, we performed a similar study, but this time at 12 NHS trusts, covering 55,500 cataract operations. That study produced many more papers looking at anesthesia, posterior capsule rupture rates – all sorts of things. AT: Just for context, there are other approaches, such as the Australian Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB) Dataset. There are some really nice data coming from Australia – but it suffers from selection bias – the data tends to come from high-end private practices, and it’s not every patient seen in all the hospitals. MH: So that is the difference between relying on statistics based on small, random samples of paper notes and using all of the data on patients seen in the ophthalmology unit – the latter is reality? AT: Yes, statistics based on small samples is modeling the population, whereas we are getting close to analyzing the whole of a population, so you just describe what you see. JZV: If Rob was still around, he would have loved the opportunity to make the most of all of these advances in big data and artificial intelligence applied to data. It’s sad that he’s not here. AT: To be honest, I would say that, because working in the highly centralized NHS environment, it’s much more possible do this than in most other healthcare systems. You have big ophthalmology departments seeing huge numbers of patients, and of course, the NHS wants to know how they are doing. DJ: In fact, one of the big drivers that made Rob very keen to start a company was a 1996 White Paper on improving healthcare standards in the NHS, which brought in the concept of ‘clinical governance’. It said that the chief executives of NHS Trusts shouldn’t just be responsible for the financial aspects, they should also be ensuring that systems are put in place to measure the quality of service being provided. This was on the back of certain scandals, such as the Bristol baby heart surgery controversy, which made the NHS realize they needed to start measuring what they were doing. And the only way to properly analyze outcomes is with a computer system, but only if it’s designed well. We used structured data from the start; the whole point was to be able to easily analyze the records. There was very little free text typing. There are some EMR systems where you literally just scribble with an electronic pen or free text type loads of information, but then you losing the richness – the ability to easily analyze all the data. I know a lot of big data analysis involves looking at reams and reams of unstructured data but, in reality, if you want to do things easily and well right now, you’ve got to have structured data – it’s a pre-requisite for decent analysis. AT: Yes – and you must have structured data to allow algorithms to learn; you have to do it right first time. The free text approach is essentially a document management system; it offers no advantage over just scanning and PDFing your patient records; you could probably convert that to text and then do text mining, but even that would be very complex.with Adnan Tufail November 2017

I got involved with Medisoft through the retina side – just talking to Rob and seeing the fantastic EMR analysis work they were doing on cataract surgery and what they’d been able to show in terms of the impact of the introduction of anti-VEGF agents. We could see that it would be a really important area to look at – these are expensive, intensive therapies, and we really need to know that our patients in the real world are doing as well as those in the clinical trials. I managed to convince a pharma company to cough up a trivial amount of money to pay for the data collection, and we did the rest ourselves. And within two months of thinking of the idea, we wrote to 16 Trusts, got replies from 14 within a month, and a month after that we had data from Moorfields. Imagine that – just two months after having the idea we had outcome data on over 100,000 injections, representing 300,000 patient visits and about 2.8 million data points! Our first attempt was in 2011; at that time, our statisticians were not used to handling big datasets, so I actually did it myself on my laptop. I am probably very fortunate in that, although I am not a proper “techie,” I was lucky to have been given a computer – a BBC Micro – as a kid, and I learned to do basic coding. But then I went to medical school. I have always been okay with numbers, but medical school knocks it all out of you! When I started doing my research, I got back into analysis. The Medisoft EMR data is very structured, but it is very difficult to deal with big datasets and link them together in something like Excel, so I wrote some basic scripts in an SPSS software package, which took me a few months to do, during my holidays in Australia. Anyway, we got some really good data out – and the first two papers were published in Ophthalmology (4)(5).

Everyone now realizes that you need to treat early and it is all about visual acuity state, not gained visual acuity. If you have poor vision, let’s say in AMD, and then treat it, the average patient will gain a lot of letters; but if you have good vision, the average patient loses vision. And the way that most people audit outcomes or the way that the data is presented in all the trials on ANCHOR and MARINA is visual acuity gain from baseline – but that isn’t what’s important to the patient. What is important to the patient is visual acuity state: not whether they have gained two letters, but whether they can still drive. It is all about getting the patient early. And it has huge implications, because it really influences clinical trial design – non-inferiority trials, superiority trials, because you can almost game the population you want to enter. So there were huge implications even in that first paper – it’s not just about asking, ‘how are we doing?’ And we realized that, at least in the UK, we weren’t giving as many injections as we thought we were (4). The vogue was not to over-treat because we were worried about the injections and the side effects, so there was a natural reluctance. The outcomes were not disastrous, but nothing like ANCHOR and MARINA – and with very few injections. So we realized we probably needed to alter the way we do things. In the second paper on second eye involvement (5) – I think Javier was the first author of that – we realized that the risk of the second eye succumbing was actually much greater than we thought. Once you start treatment in one eye, if you have reasonably good vision in the fellow eye, you have a 50 percent risk of developing wet AMD within three years. Again, this has huge implications in terms of the extent of treatment required, and what happens when both eyes are involved. I did the analysis of the first two myself – but it was pretty tiring to do the day job as well. I realized that it would be nice to get much better coders involved and I was very fortunate to meet some extremely good data guys, who also understood the eye. There was Dave Crabb’s group at City University in London, and a fellow, Aaron Lee – a rare individual who not only codes brilliantly but is also a retina specialist. So we then developed a group with me, my wife [Cathy Egan], Dave Crabb, and Aaron – and then it really took off; my ability to code was no longer the limiting factor. Once we had brilliant people on board, we just started free-thinking about what we could do, and not just limiting ourselves to conventional outcomes. For example, we started looking at novel health economic analysis, such as how in the UK at the moment you still can’t treat eyes with vision better than 6/12 (20/40). With health economics analysis, you need to establish that what you are doing is incrementally more cost-effective than the standard of care. But the standard of care is unknown because in the trials there is no control arm better than 6/12. It was Rob who bounced the idea around and realized that the data probably existed in Medisoft. There were a few areas in the UK where they were funding vision better than 6/12, so we mined that fellow-eye data, and their OCT data, and when we had a leap on the OCT for two successive visits, we followed it through until they got an injection. That was the natural history arm; then there were centers that had the injection, and that was the real arm. So we then did a health economics analysis, and showed it was highly effective even with an ICER analysis; there is a whole level of complexity above that. It has been studied in the current NICE AMD review, and we hope it will change things.

We have done a similar study now with AREDS, which was published recently (6). The UK doesn’t offer AREDS vitamin supplementation. The AREDS formulation is known to be effective for preventing wet AMD in people who’ve got the wet form in one eye and the dry form in the other, and we were very lucky to do a hybrid health economic model. Emily Chew of the NEI gave us full access to the original AREDS dataset; we merged that with real-life outcomes and got a NICE-level health economic model. It turned out that AREDS aren’t just “cost-effective,” if you’ve got wet in one eye and dry in the other – they are what’s called “dominantly cost-effective.” In other words, if you pay for it, it still saves the NHS money – to the tune of £130 million a year per cohort you enter. It wouldn’t be possible to show that without our combination of data. I believe the approach is going to be transformative, not only for outcomes – by ensuring that we are modifying our behavior in the UK – but also for health economics. We also have the potential to “free think.” I had a fellow operating on my list, a brilliant surgeon, and he had a complication. We looked up the EMR records and found that the patient had received about 22 anti-VEGF injections. A few weeks later, the same thing happened. We looked up the notes and found that the patient had received 30 injections! I thought, we’re injecting the eye, we’re not seeing obvious trauma, but this may be because you are injecting and somehow weakening the lens. As I said, this is a rare event, and it has been very difficult to prove the association – even when it’s the two most common procedures in ophthalmology – cataracts and injections. Within 48 hours of asking the question, Aaron analyzed the whole dataset (because he had access to the cataract data and rupture rates) and realized that actually there is an increased risk per intravitreal injection: when you have more than 10 injections, your risk of complications or posterior capsule ruptures is the same as a junior surgeon or a resident surgeon – it has that much of an impact! Such knowledge is important as it changes how you advise your patients. We realized that we can actually do more than simple outcomes. We are now at the next stage: looking at different procedures within the eye, and how they interact – and trying to understand how that affects the rest of the body.

Now, the challenge is merging other public EMR datasets, which is ethically complex; however, we are now linked to the Farr Institute, one of the four government-funded Health Informatics Institutes, to link eye data to cardiovascular data to GI data. We can start looking at uveitis (we did an editorial on big data in uveitis in Ophthalmology not so long ago [7]), about how it interacts with the body. What drives machine learning and trains a deep-learning algorithm (or any machine learning algorithm) is lots of data. Now, we are using our data to drive the next generation of machine learning, and not just in terms of analysis of images. We’re working with a number of groups: we are linked to the University of Washington, where Aaron is now, and we are part of the last ever big European grant. We are also doing more complex things; we have a very large pharma grant of about £2,000,000 to link imaging to the EMR data in search of the Holy Grail: can we predict what is going to happen to a patient, and select them out? In other words, if we’ve got a predicted poor responder on the basis of various factors, can we switch them onto other clinical studies or other therapies? We have 43 million OCT slices from the service at Moorfields now linked to the EMR data, which is going to drive all of that effort. It’s our next big challenge. And all of this was inspired by Rob – none of it would have happened without him. He has also inspired other important research in this area. On that basis, I thought it would be a good idea to do a Special Interest Group at ARVO a few years ago; I invited Mark Gillies – because he was doing some FRB, and we also talked about cataracts – and I invited Dave Crabb to talk about glaucoma, and Aaron to talk about data visualization, and the group really took off. Then, the American IRIS registry group came on board, and kind of took responsibility for it last year, and invited me to be on an all-day big data course. Many pharma companies were present, and now they’re all interested in big data research. This whole evolution of data-driven research was triggered by Rob’s work. Without him, the tipping point would probably have been many years later.

Finding time

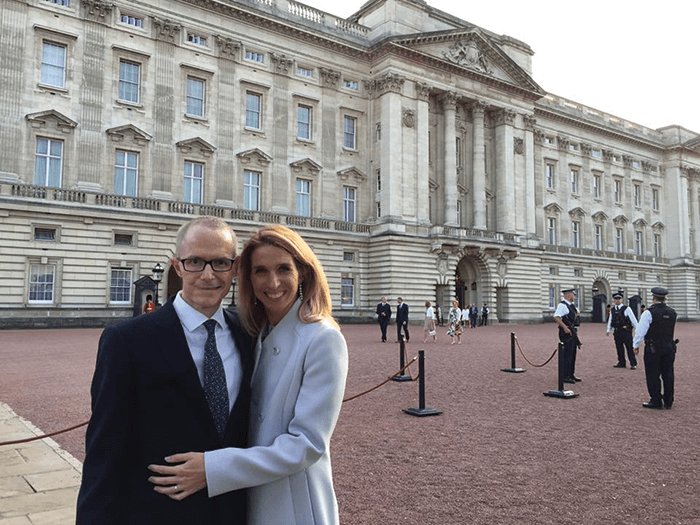

JZV: Even when he was the busiest man on earth, Rob always found time for his friends. At every conference we attended, I would get a message from him to meet up for a meal or something no matter how full his agenda was. In the middle of a conference with 5,000 attendees or even 20,000 like ARVO, it felt really special. He once got a cab across Seattle just to have a cocktail with me. I really like attending meetings not just because of all the professional aspects but also to be with friends – and Rob was more than my mentor, he was one of my best friends in this ophthalmology world. Maintaining any relationship usually requires some effort – but with Rob it was always spontaneous and bilateral. I always did my best, and he was always there, and I am really going to miss him. MH: Shall we talk about Rob running the New York Marathon? AT: David, I’ll leave this to you, but I understand that it was the first time Rob knew something was wrong, because his time was a bit slow – no? DJ: How I remember it was that he did the New York Marathon on the weekend, and then came back, got straight off the plane to give a talk at Peterborough Hospital about Medisoft; we were implementing it in a glaucoma shared-care scheme at around the end of 2004. While we were waiting to give the talk, Rob doubled up in pain and grabbed hold of his gut – and I knew, because he was a very stoical kind of guy, that it was serious. He still gave the talk. We obviously knew something was wrong, but thought it was Crohn’s disease or diverticulitis. I got the news about a week later and we were all devastated: cancer of the colon. He was only 38 at the time. AT: Rob was just as stoic the whole way through. At the last RCOph meeting, he looked a bit weak, but amazingly he actually had a chemotherapy infusion pump while walking around, meeting and greeting people normally. There were never any excuses with Rob. He was always on the ball and never complained; it was unbelievable. DJ: Even privately, with his family, he was the same; he never complained, he just got on with it. JZV: In January of 2016, he came over to Barcelona for a very quick weekend break with his wife, Alice. We went for lunch with my wife and daughter, but this time it was different; he told us that the cancer had come back again – and that it was bad. Later that same day, we ended up visiting Gaudi’s Casa Mila (La Pedrera) and we all went to the roof. He was wearing morphine patches and never complained at all during the all-day tour. I was not prepared for his bad news, and I will always be grateful that I had the chance of a proper goodbye six months later (one month before he passing away) we all went to the Boqueria Market for tapas. It is my final great memory of Rob. DJ: I remember when he had his first chemo cycle back in 2005, he would just have a week off for chemo, and then go back to work. Here’s something that he never even told me – just typical of Rob: after he had quite disfiguring facial surgery for the second primary cancer he got in his parotid gland, he was still seeing patients. One patient thought that it was amazing that he was still working as a doctor and doing his job, so they wrote to Prince Charles. In turn, Rob received a letter from Prince Charles! I didn’t even know until Alice showed me the letter... AT: Typical Rob. DJ: Just before he died, he got a Queen’s Award for Enterprise; he went to Buckingham Palace, but unfortunately missed the Queen – he had to nip off to the toilet suddenly – but Alice managed to meet her. JZV: I like to think that he is somehow still with me. As I told the crowd at his memorial service (which Adnan and David will remember), I still hear his voice. When I operate, I hear the voices of the three guys that taught me how to perform vitrectomy. First, there’s Nigel Kirkpatrick telling me everything must be under control prior to starting the procedure; then there’s Ahmed Sallam, telling me to have a plan beforehand and stick to it; and the third voice is just Rob… When I am operating a case and am in the middle of something and thinking, “What now?”... I can clearly hear Rob telling me (nicely): “You are wasting time!” Therefore, I feel afraid and get on with it. I love the idea that Rob is still with me! From a personal and a professional point of view – what a star he was!References

- FG Holz et al., “Multi-country real-life experience of anti-vascularendothelial growth factor therapy for wet age-related macular degeneration”, Br J Ophthalmol., 99, 220–226 (2015). PMID: 25193672. RL Johnston, JM Sparrow, CR Canning, D Tole, NC Price, “Pilot National Electronic Cataract Surgery Survey: I. Method, descriptive, and process features”, Eye (Lond), 19, 788–794 (2005). PMID: 15375370. JC Javitt, “Rule Britannia”, Eye (Lond), 19, 727–728 (2005). PMID: 15999114. Writing Committee for the UK Age-Related Macular Degeneration EMR Users Group, “The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: multicenter study of 92 976 ranibizumab injections: report 1: visual acuity.” Ophthalmology, 121, 1092–1101 (2014). PMID: 24461586. J Zarranz-Ventura et al., “The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: report 2: incidence, management, and visual outcomes of second treated eyes”, Ophthalmology, 121, 1966–1975 (2014). PMID: 24953791 AY Lee et al., “Cost-effectiveness of age-related macular degeneration study supplements in the UK: combined trial and real-world outcomes data”, Br J Ophthalmol., Epub ahead of print (2017). PMID: 28835423. CS Lee et al. “Big Data and Uveitis”, Ophthalmology, 123, 2273–2275 (2016). PMID: 27772646.