- Changing reimbursement requirements are causing uncertainty and uneasiness – and many doctors mistrust the system

- One key change is the switch from fee for service to quality-based assessments based on patient satisfaction

- In an era of regulatory reform, we overview the current situation and the potential future

- We discuss problems with the system and we offer practical solutions to overcome these uncertainties.

How do physicians feel about compensation being tied to quality of care in medicine? Our guess: disconcerted. Not because physicians don’t know how to provide quality care, but because they don’t trust how it is measured. Providers across the country are trying their best to keep up with the shifting sands of what is required of them by Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurers regarding how their reimbursement will be connected to quality of care. In hospital-based practices, the hospital CEO may have a plan, and in academic departments, the chair and the Dean may also have a strategy. In this article, we will briefly review the current state of affairs, the possible future, and offer guidance on how best to deal with the uncertainties surrounding the future of compensation models (1)(2)(3)(4).

The current situation

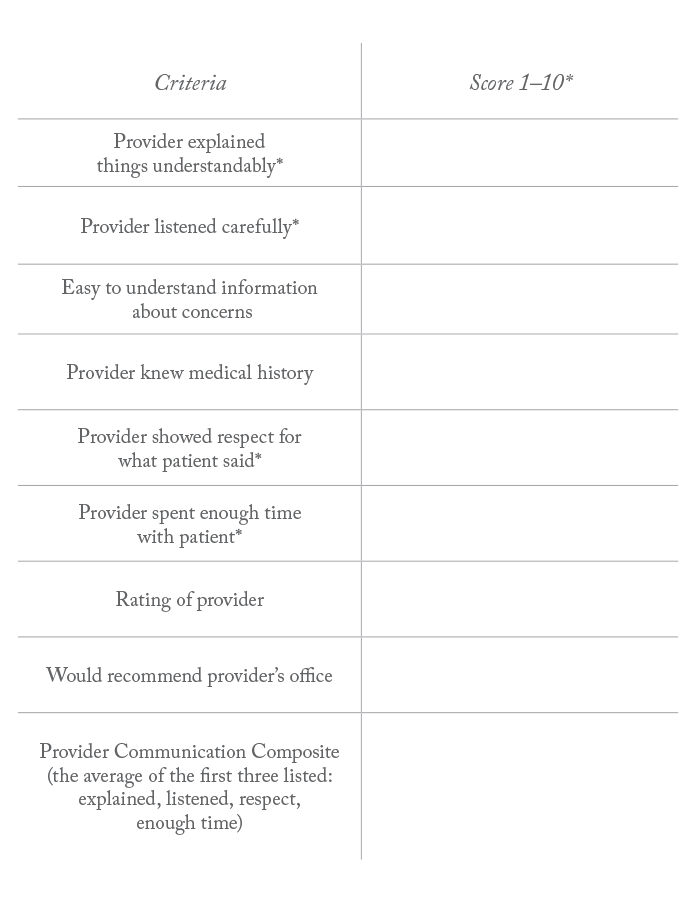

Physician compensation in the United States is primarily based on fee for service, but things are changing to connect physician compensation to value (quality + satisfaction/cost). The Affordable Care Act (ACA), and its many amendments, legislates that providers and hospitals must track quality metrics, or be subject to financial penalties that affect physician salaries. From the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), we started in 2006 with Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) and then Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS), and in 2015 it became Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Now, it will be all rolled up with Alternative Payment Models (APM) under the newest banner, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA). Meaningful use basically incentivizes compliance with electronic health record (EHR) keeping and its utilization, and is a quality metric that improves care, but this is not what will be discussed here. Instead, we will focus on what is commonly referred to as non-performance based incentives (NPIs), using patient satisfaction as our example. Table 1 lists commonly tracked (subjective) variables that could make up NPIs.

A number of companies track and survey every patient seen within a health organization, and provide scorecards so physicians can compare their performance within their institution and nationally with their peers. Organizations also develop or purchase internal systems to track patient satisfaction in real-time. Whilst the intentions of organizations collecting this data are well meaning and worthy of respect, and appear logical and organized, survey strategies vary by methodology (electronic, paper, telephone, cell phone), as well as question content (limiting the number of questions or differences in length and complexity of individual questions). The lack of standardization makes comparing the results of practices around the country suspect. Additionally, physicians are uneasy about tying their salary to quality metrics where there is substantial data subjectivity as well as many sources of potential measurement and reporting errors. Below, we briefly review some areas of potential error.

- Not comparing apples to apples Accumulated data for a given period (sometimes every two months) can be given to a provider in the form of a physician scorecard. The doctor can analyze the accumulated, averaged numeric results or convert this average to a percentile rank for comparison with other physicians and hospital systems. The major error here – especially for ophthalmologists – is that we are a highly subspecialized group and the survey industry has not yet caught up with this concept. Trying to compare the nature of work, or a given survey population, of a uveitis specialist in an academic hospital to a high-volume cataract surgeon in a small town is simply not going to reflect the realities of what is happening with patient care.

- Patient error Patients frequently do not answer surveys accurately. In our own experience, there have been many instances of patients mistakenly scoring 1 (lowest ranking on a scale of 1–10) when they meant 10. One result like this, when there may only be 50 patients responding in the tracking period, can be devastating to a physician scorecard and overall percentile rank.

- Narrow percentile rank window The range of scores separating top and bottom quartiles is extraordinarily small. For instance, examine the metric of “rate the provider” in a typical patient satisfaction survey; one doctor is rated 10 out of 10 in 78 percent of evaluations, while another doctor in a different part of the country may score 10s in 80 percent of their evaluations. Converting these average scores to percentile rank, the first doctor is at the 25th percentile and the latter doctor at the 50th percentile nationally. The difference is only 2 percent, but the first physician’s pay is docked because they are below the 30th percentile benchmark. Take this strict benchmark and then consider one of your patients accidentally gave you a 1 out of 10, putting you below the benchmark, one can then understand the frustration which mounts in the physician community. Additionally, a provider in an upscale low-acuity facility with a relatively affluent patient mix may face different satisfaction challenges compared with a provider practicing with a high acuity case-mix in a very poor, very urban, and culturally diverse setting. How is this comparison fair?

- Low number of completed surveys Science dictates that we must have a large number of subjects tested to trust a result. If only 10 percent of patients respond to surveys, a selection bias occurs. Those responding may only be the ones who have something to say, and many times, the ones who are vocal have a complaint. It is true that excellent care can lead to positive remarks, nevertheless, how can a physician trust that the respondents represent a real evaluation of their quality of care? Physician scorecards may only have 10 respondents and others may have 200 or more. Comparing groups and penalizing or rewarding compensation on such wide discrepancies will be viewed as unfair unless reliability and accuracy of survey results are well-understood and acceptably valid.

- Intra-specialty comparison errors A major issue with quality tracking is that some specialties, just by the nature of the practice, will score lower than other specialties. A pain management specialist sees patients in pain all day. A cataract surgeon restores sight all day. Which specialist will score better? Does the cataract surgeon provide higher quality of care just because his scores are higher? Glaucoma management is not a sight restoring practice, it is a sight preserving practice. Neuro-ophthalmology consists of patients with complex diseases that are difficult to understand and live with. How can we compare a neuro-ophthalmologist or a glaucoma specialist to a LASIK surgeon? Additionally, practices consisting of a majority of long-term patients are very difficult to compare with practices primarily made up of brief episodes of care commonly found in specialty care. Is the satisfaction of a patient similar between these two settings? These questions are rhetorical as there don’t appear to be any fair answers at this time.

- Government The government keeps moving the needle and changing its requirements. The fact that the ACA created PQRI, then PQRS, and then MIPS should tell you that we cannot predict the future. Will Obamacare be repealed or will it evolve and change? This uncertainty leads to uneasiness in the physician community. What does appear certain, however, is that quality will count. How much it counts and how accurately and fairly the government applies financial penalties for non-compliance are the real questions.

Dealing with Uncertainties

Here, we present some solutions to the imperfections that are discussed above:- Intrinsic motivation Doctors want to provide quality care; however, financial incentives and penalties may be creating perverse effects on quality. If doctors prioritize pleasing patients, inappropriate prescriptions and reluctance to deliver truthful or bad news may be the result. Obviously, this isn’t how we practice but there is a sliver of truth to this concept. Recent articles have suggested that our innate desire to work, and the satisfaction we derive from quality work is as important to an individual as hunger or thirst (1). The future of quality care must focus on this intrinsic motivation that physicians possess. After all, for most of us, the drive to relieve pain and suffering is the main reason we became doctors in the first place.

- Compare similar organizations We must compare similar practice settings, such as academic institutions to other academic institutions, and private practices to other private practices, from similar parts of the country. Data needs to reflect that a glaucoma surgeon in an academic department in Philadelphia is not the same as a private practitioner in mid-Missouri. The good news is organizations that track quality data are becoming more sophisticated over time and intra-specialty comparisons should become more accurate in the future.

- Improve infrastructure and increase support staff There are two key elements we believe will improve patient satisfaction, and hence improve quality of care, scores: improving infrastructure and supplying ample support staff. Well-staffed, clean, and modern facilities provide patients a concierge experience, similar to what might be found in a nice restaurant with valet parking or flying business class on an airline. Older, understaffed clinics could have a major impact on the overall “rate the provider” and/or “communication” scores. If an organization is having difficulty improving quality scores and many of the metrics have been extensively addressed over the preceding months/years, focusing on infrastructure and staffing seem likely to have a significant positive impact. The entire patient experience surrounding a health care visit reflects upon the physician regardless of the one-on-one interaction between patient and doctor.

- Thresholds for success The benchmarks for success are many times set by the organization. Setting the benchmark at the 30th percentile could enable physicians to improve over time. If the benchmark is at the 50th percentile, and historically the organization has been at the 17th percentile for years, there could be morale problems and loss of physician engagement without a celebration of the incremental successes. The hill may be simply too steep to climb if rate of change is unrealistic. Early on, set achievable goals and then move the goals to more ambitious levels as survey or other results improve.

Concluding thoughts

The goal of physicians and hospitals is to provide the highest quality of care possible. The system is fraught with complexity and errors well known to physicians, and therefore many doctors do not trust the system to fairly apply quality metrics that affect physician compensation. Still, there are many solutions to the problems we face. The keys are to have patience, and to apply a multi-faceted approach to quality improvements. It is important to improve subjective survey methodologies while also improving the whole patient care experience, which must include adequate infrastructure and a fully staffed clinic. If we, as a healthcare community, can accomplish some of these goals, then doctors will be able to trust “the system” and patients will get the quality care that they deserve. Frederick Fraunfelder is Chairman and Roy E. Mason and Elizabeth Patee Mason Distinguished Professor at the University of Missouri, Department of Ophthalmology. Stevan Whitt is Senior Associated Dean for Clinical Affairs at the University of Missouri School of Medicine and Chief Medical Officer for MU Health Care.References

- DH Pink. “Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us.” Riverhead Books, New York, NY: 2009. AT Chien et al., “Physician financial incentives and care for the underserved in the United States”, Am J Manag Care, 20, 121–129 (2014). PMID: 24738530. ME Porter. “What is value in health care?”, N Engl J Med, 363, 2477–2481 (2010). PMID: 21142528. TH Lee, A Bothe, GD Steeler. “How Geisinger structures it physicians’ compensation to support improvements in quality, efficiency, and volume”, Health Aff, 31, 2068–2073. PMID: 22949457.