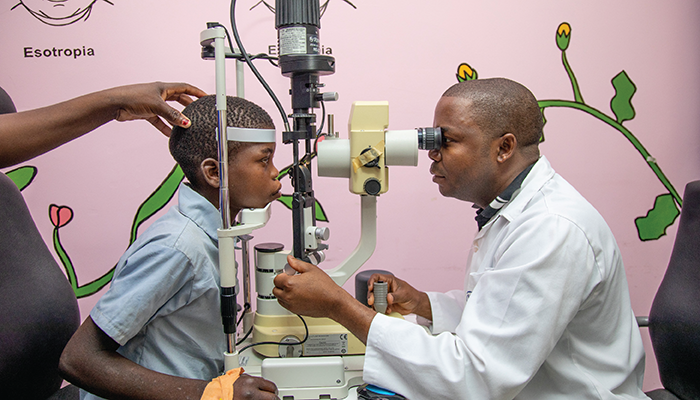

Dr. Vasco Da Gama inspects a unilateral cataract patient. Credit: All images supplied by Super Midia.Phill ( SMP) "Light for the Word"

Can you imagine being the only eye care specialist in a country of 32 million? The Ophthalmologist caught up with Isac Vasco da Gama, the leading pediatric ophthalmologist in Mozambique, who (until very recently) didn’t have to imagine such an overwhelming task.

What led you into pediatric ophthalmology?

I initially trained at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University. During my time there, I encountered many different diseases – but the most challenging were in pediatrics. I also saw first-hand the benefits of treating a child; you gave them their sight back for many more years. For a child who is less than a year old, successful eye surgery can mean that they live their whole lives, maybe another 80 years, with good vision.

Until recently, you were the only pediatric ophthalmologist in the whole of Mozambique. Can you describe that experience?

When I finished my fellowship in pediatric ophthalmology, I quickly realized that, in a country of more than 32 million with a pediatric population of around forty-five percent, I had about 14 million children to think about. That was a very daunting statistic for me! Even before I finished my training, I started interacting with an NGO, Light for the World, and we looked at proposals to establish a sustainable pediatric ophthalmological practice in the country. We have achieved that now — at Quelimane Central Hospital, Light for the World have sponsored the building of dedicated operating theaters in the eye department and renovations to make the department more child-friendly. There has also been a significant investment in specialist equipment and medicines. But it was very difficult in the beginning. I had to travel from one province to another for training sessions, just imparting the basics of pediatric ophthalmology to other eye care professionals. But I knew I had to spread this knowledge to others; I couldn’t do everything myself.

I taught general ophthalmologists, ophthalmic technicians, and other health workers strategies to identify more children who need ophthalmological attention and then refer the children to me. The approach seems to be working. I also attend symposiums and national conferences to help increase awareness of pediatric ophthalmology, and the audiences at the events are beginning to see the value of it.

I would say that in the next three to four years, things will become more manageable. By then, the two other pediatric ophthalmologists I have trained will be more experienced, and we can begin training more general ophthalmologists in pediatric ophthalmology.

What are the main challenges you encounter in pediatric ophthalmology in Mozambique?

Awareness of pediatric eye care is the main problem – from parents and patients to health providers at the peripheral level. The number of children I currently treat is not proportional to the number we should be treating, given that we are the only pediatric referral center in the country. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one in 10,000 children have cataracts. That means there are around 2,000 children with cataracts in Mozambique. But I operate on maybe 20 children each year, which means there is still a lot of work to be done in terms of public awareness. We are working to improve this, for example, through training teachers to detect eye issues in schools and refer pupils.

Another challenge is funding. Currently we run awareness classes in only 47 of around 1,000 schools in the country, which means less than five percent of students are being taught about eye health. We definitely need to extend our reach to many more schools, which of course requires more funding.

Dr. Vasco da Gama, Head of the Eye department at Central Hospital Quelimane

What specific eye diseases are prevalent in the country?

I would say the most frequent eye diseases are refractive error, allergic conjunctivitis, cataracts, and strabismus.

We also have malignant tumors, such as retinoblastoma. This needs to be emphasized; even though it is considered rare, retinoblastoma can be a life-threatening condition. In just one month, I see one to two cases of retinoblastoma. For children with advanced retinoblastoma, I can only think of only two that I have treated that are still alive; fortunately, they came in time for us to do something for them. But for most of these patients, I do not have enough information and the retinoblastoma is too far advanced. Raising the profile of this disease would help immeasurably. It is important to create a sustainable and efficient retinoblastoma program for community workers and primary healthcare workers, so that they can then refer these cases to ophthalmologists early. At our specialized center for retinoblastoma, we can consider laser treatments and other expensive options, but any ophthalmologist should be able to perform enucleations if they have the proper knowledge and equipment.

We also need more oncologists and specialist centers. Currently, there are only three centers in Mozambique offering chemotherapy. If a child comes in with these types of diseases, we are effectively unable to help them because of a lack of equipment and lack of medicine. So we desperately need a specialized, fully equipped program for retinoblastoma.

Dr. Vasco Da Gama removes surgery dressings

How else can we help improve pediatric eye programs?

I would recommend that pediatric eye programs are seen as a priority, not only within eye care, but in the overall healthcare profession. If we want to ensure a good future for the country, we need to protect children’s sight. In terms of serious eye conditions, NGOs and people involved in running charity programs need to consider pediatric eye care in their planning because this will help to develop the entire country.

That is the main message I have: let’s prioritize pediatric programs.

Dr. Vasco da Gama screens a patient after cataract surgery

This article first appeared in The New Optometrist.