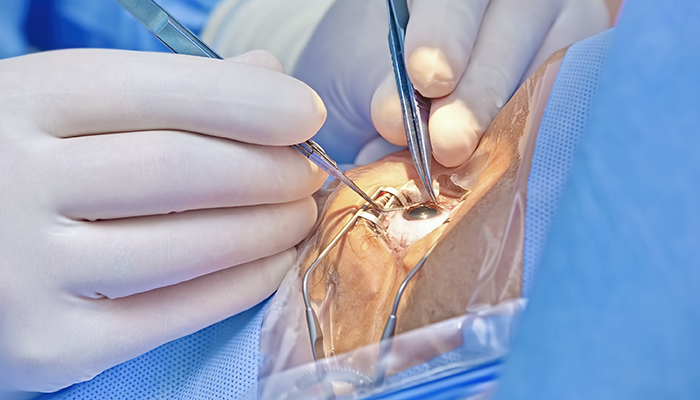

Credit: Surgeon Image sourced from Shutterstock.com

Credit: Surgeon Image sourced from Shutterstock.com

Cataract surgery in patients with pre-existing glaucoma presents a number of potential challenges – particularly for those patients who have undergone prior filtration surgery, such as trabeculectomy. As we all know, the conjunctiva doesn’t like additional procedures!

Phacoemulsification is a known stimulus for conjunctival fibrosis and subsequent bleb failure. Phaco is often a “silent enemy” (1), as bleb failure and rising pressure occur after classical cataract follow-up has passed. As phaco become increasingly streamlined, there is less follow up – or sometimes no follow-up at all – after routine surgery. Historically, trabeculectomy was the most common glaucoma surgery performed and, given that the surgery itself increases cataract progression, it’s likely that this phaco versus bleb collision may also increase. It is not just a trabeculectomy issue; the rise of bleb-forming minimally invasive glaucoma surgery techniques dictates that bleb-dependent surgery may be more posteriorly draining and not have such obvious limbal changes, such as a helpful surgical iridotomy, to alert the unsuspecting phaco surgeon of its presence. All cataract surgeons must look for a bleb.

Pre-op considerations

In the pre-operative period, the patient must be appropriately counseled and consented on the potential risk of bleb failure following cataract surgery. The literature estimates that around 10–35 percent of functional trabeculectomies fail in the two-year-period following cataract surgery (2). However, a study by Rashmi and colleagues found no statistically significant difference between failure rates in patients having undergone trabeculectomy versus trabeculectomy following cataract surgery within five years of follow-up (3). Only 17 of 60 procedures used 5-fluorouracil (5FU) at the time of cataract surgery or in the immediate post-op period. No statistical difference between overall success was found between those with and without five-year follow up in association with cataract surgery. Conversely, another study, in which most patients underwent extracapsular cataract extraction, demonstrated that cataract surgery does increase failure rates – and that the shorter the interval between trabeculectomy and cataract surgery, the higher the risk of failure (4). Where possible, cataract surgery should be left at least six months after trabeculectomy, although significant evidence for exact timings are not currently available; notably, in the quoted study, most patients underwent extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE). Conversely, a recent study in the Journal of Glaucoma demonstrated that the 24-month failure rate was lower in patients undergoing combined phacoemulsification + trabeculectomy (phaco-trab) versus trabeculectomy alone (5).

What about biometry?

Following trabeculectomy, there is a significant and persistent reduction in axial length (AL). There is also a transient decrease in anterior chamber depth (ACD), but it deepens and returns to normal around two weeks after surgery (6). Most studies also demonstrate induced with-the-rule astigmatism, with a mean of 0.81 ± 1.08 D at three months post-op, which tends to resolve within one year but can persist (7). Some experts propose that the increase in astigmatism may be caused by several factors, including tight scleral flap suturing and wound gape from the internal sclerostomy. Superior corneal steepening secondary to contraction of tissues at the trabeculectomy site, overhanging bleb, and post-operative ptosis may also be late contributing factors (8). However, these are likely to be less significant the longer the duration following trabeculectomy, given stabilization of anatomy and biometric values usually by 12 months.

One study investigated the refractive outcomes in patients undergoing phacoemulsification and intraocular lens (IOL) implant at least three months post-trabeculectomy, comparing eyes with medically controlled glaucoma or no glaucoma. The main outcome measure was the difference between predicted and actual postoperative refraction. The difference from expected refractive outcome was -0.36 (more myopic) in trabeculectomy eyes compared with +0.23 (more hyperopic) in non-glaucoma controls, and +0.40 in glaucoma controls (P < .0001). Final visual acuity was not affected, but there was an increased requirement for refractive correction post-op. The refractive differences correlated to intraocular pressure (IOP) change, with a 2 mmHg rise resulting in a -0.36D myopic shift, likely related to an increase in axial length (9). A 2022 study found the Barrett Universal II formula to be more accurate in predicting the postoperative refraction than SRK/T in eyes undergoing combined cataract surgery and trabeculectomy (10). Moreover, Barrett Universal II may be less susceptible to the effect of axial length and corneal shape than others, such as SRK/T, making it more predictable in this patient group.

What about IOL choice?

Discussion around the most appropriate IOL type for patients with prior trabeculectomy will depend on other ocular comorbidities but will predominantly depend on the severity of glaucomatous damage. Particular attention should be placed on central visual field loss and the degree/type of astigmatism. Generally, avoiding multifocal and trifocal lenses is advisable in glaucoma. Extended depth of focus (EDOF) lenses could be considered (and remain my own personal preference), but we must preserve the central visual field (VF). I also consider the likelihood of central VF involvement in the future – it’s possible then to consider proceeding with a monofocal and the relative forgiveness they offer. I consider a toric if astigmatism is greater than 1.0D, but will also consider the pupil size/mobility (and the ability to accurately align a toric). Increasingly, I implant EDOF lenses in patients without central VF loss, as their extended depth characteristics can effectively minimize post-trabeculectomy biometry limitations by allowing a slightly hypermetropic target and letting the lens characteristics give some added myopic effect to facilitate distance and intermediate vision. A monofocal implanted with the same strategy would need refractive correction for all focal lengths.

Protect thy bleb!

Surgical planning to preserve the anatomy – and to minimize the inflammatory response in and around the filtration bleb – is paramount. Topical and intracameral anesthesia is preferable to sub-tenons or subconjunctival anesthetic to reduce subconjunctival stretching, manipulation, hemorrhage, and inflammation, which may spread to the bleb area superiorly. Following a sub-tenon's anesthetic, massage of the globe is also best avoided.

Corneal incisions should be placed temporally away from the bleb area, with good architecture and form. The anterior chamber is often more shallow and fluctuates more readily compared with eyes without trabeculectomy due to persistent relative low IOP. A reduction in phaco-machine bottle height and IOP is desirable to reduce overall fluid turnover through the bleb. Don’t be tempted to increase the bottle height/IOP to obtain a more stable AC – it just encourages more flow through the filter carrying potentially inflammatory factors, and rarely deepens the AC. I often use intracameral dexamethasone (0.66 mg in 0.2 ml) to reduce anterior chamber inflammation in the early post-operative period.

Monitor bleb morphology, not IOP

The benefit of intraoperative injection of 5-FU to the bleb is in widespread use and I personally use it after every case with a functioning bleb, but studies have demonstrated mixed results (3, 12). One study found 5-FU has a protective effect on functioning blebs, with a lower incidence of postoperative IOP spikes and a reduced need for additional IOP-lowering medications at 12 months (13). There remains no clear message, but I personally feel the risks of subconjunctival 5FU are outweighed by the potential benefit on bleb function.

These patients require more frequent follow-up – concentrated around weeks three to eight – compared with patients who have phaco only. Bleb assessment is vital when looking for subtle morphology changes, inflammation, and hyperaemia. Don’t wait for IOP rise as the only sign of potential failure because this occurs late; the ship has often already sailed once a significant rise in IOP has been detected.

My personal post op regime is to use a higher-frequency steroid and for longer. A preservative-free formulation would also be preferable to preserve ocular surface health and comfort, especially as these patients may be more prone to dry eye disease. It is important to treat the patient and bleb individually, rather than using a standard post-cataract regime. If the bleb morphology alters and fibrosis is detected, I increase steroid frequency and add extra weeks to the taper. Consider a subconjunctival injection of steroid and 5FU to the bleb between weeks three to eight – again, before IOP rises. It’s always better to be proactive here, as a small injection is preferable to a formal needling or second filtration operation if the bleb is allowed to fibrose.

References

- RG Mathew, IE Murdoch, “The silent enemy: a review of cataract in relation to glaucoma and trabeculectomy surgery,” Br J Ophthalmol, 95, 1350 (2011). PMID: 21217138.

- R Husain R et al., “Cataract surgery after trabeculectomy: The effect on trabeculectomy function,” Arch Ophthalmol, 130, 165 (2012). PMID: 21987579.

- RG Mathew et al., “Success of trabeculectomy surgery in relation to cataract surgery: 5-year outcomes,” The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 103, 1395 (2019). PMID: 30472659.

- PP Chen et al., “ Trabeculectomy function after cataract extraction,” Ophthalmology, 105, 1928 (1998). PMID: 9787366.

- Y Winuntamalakul et al., “Two-year outcomes of trabeculectomy and phacotrabeculectomy in primary open angle versus primary angle closure glaucoma,” Journal of Glaucoma, 32, 374 (2023). PMID: 36728543.

- A Alvani et al., “Ocular biometric changes after trabeculectomy,” Journal of ophthalmic & vision research, 11, 296 (2016). PMID: 27621788.

- KG Claridge et al., “The effect of trabeculectomy on refraction, keratometry and corneal topography,” Eye, 9, 292 (1995). PMID: 7556735.

- S Egrilmez et al., “Surgically induced corneal refractive change following glaucoma surgery: nonpenetrating trabecular surgeries versus trabeculectomy,” Journal of cataract and refractive surgery, 30, 1232 (2004). PMID: 15177597

- N Zhang et al., “The effect of prior trabeculectomy on refractive outcomes of cataract surgery,” American Journal of Ophthalmology, 155, 858 (2013). PMID: 23398980.

- K Iijima K et al., “Predictability of combined cataract surgery and trabeculectomy using Barrett Universal Ⅱ formula,” PLoS One 17 (2022). PMID: 35737663.