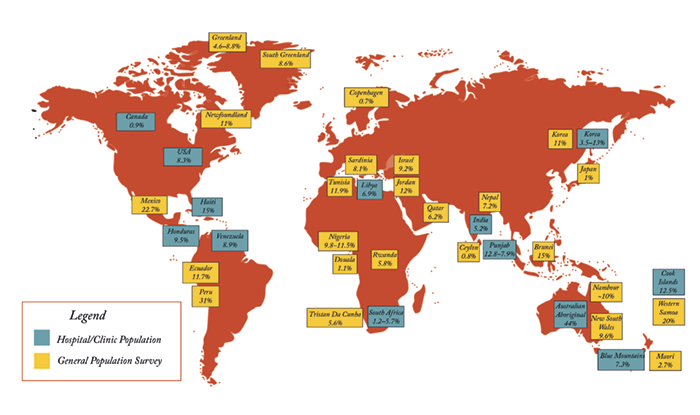

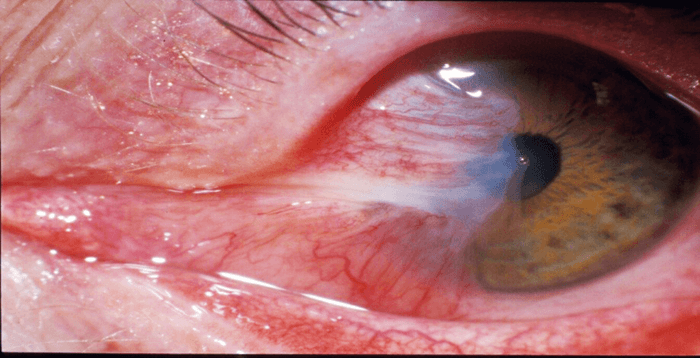

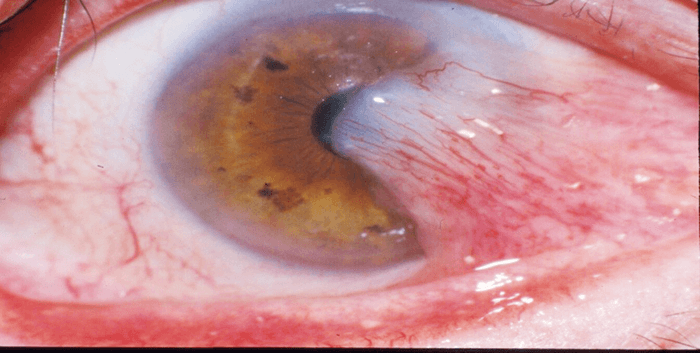

Northern Australia is rife with pterygium, the conjunctival disorder that’s seen primarily in tropical and some subtropical regions of the world (Box 1). It’s characterized by a non-malignant, slow-growing proliferation of fibrovascular tissue over the cornea, and the disease processes involve a fibrovascular reaction, chronic inflammatory cell infiltration, angiogenesis, and fibroblastic proliferation and invasion (1). But if you needed to choose a single word to describe it, you probably wouldn’t choose ‘pretty’ (Figure 1). In Brisbane, Queensland, where I was born, raised (and went to medical school), almost every ophthalmologist removes them as a routine part of their practice. They consider it to be a trivial disease and want to perform the simplest surgery to get rid of it. During my undergraduate days back in the late 1960s, most people just scraped it off in the office and sent the patient off for radiotherapy to prevent recurrence. I left Brisbane in 1973 and travelled 1,000 miles south to work in Melbourne, which was followed by stints in the US: Baltimore in 1976, then St Louis, Missouri in 1983. I saw hardly any cases during my travels away from home. But in 1986, I returned to the Princess Alexander Hospital in Brisbane and was faced, once again, with many cases of terrible pterygium.

Pterygium might often be thought of as being a trivial condition – and frequently, it is. But occasionally, it’s blinding. At the time, what struck me most was that the methods being used to treat pterygium could actually lead to patients losing their vision – or even their eyes. The biggest villain was radiotherapy: it can cause scleral necrosis, leading to scleral thinning, which leaves patients’ eyes more vulnerable to infection. We all know the potential consequences of endophthalmitis. One problem with a “trivial” disease is that it does not receive much attention. Beyond one or two small studies, there was no real data on the true incidence of pterygium in the country – and certainly very little scientific research into how to treat it. It was just word of mouth: “Gee, that seems to work, so we’ll do it too.”

The application of science

The first thing I did after seeing such terrible cases on my return to Australia was to try and put some science into the subject: epidemiology and statistics. To build our framework, we needed to understand two aspects of pterygium: how often it occurred, and the success and complication rates of existing treatments. The first part was dealt with through collaboration – someone was organizing a dermatology population study in a city not far from Brisbane (2), so I got involved. It turned out that the pterygium prevalence rate in this city was 10 percent of the population aged over 18 years – making it an extremely common condition – and it was likely to be similar across Queensland. The second task was to examine the success rates of existing treatments. The recurrence rates at the Princess Alexandra Hospital were 42 percent (3)! And that made it clear to me that we not only had a very common disease, but it was also being poorly treated. Later, we found out that you need to follow patients for at least a year – doing so identifies 97 percent of all recurrences (4). We then tried to identify over a thousand consecutive patients who had been treated with radiotherapy (around 25–30 percent of patients with pterygium received radiotherapy at the time). We were looking for patients 10 years after radiotherapy – but, of course, it’s very difficult to follow patients a decade after a treatment. Nevertheless, we did find 500 of the 1,000 – 13 percent of whom developed scleral necrosis; and two lost their eyes because of endophthalmitis thanks to a thinned sclera (5). I’m moderately proud of my achievement: it helped me manage to knock radiotherapy on the head for pterygium in Queensland, so it’s very rarely used now. And though I may be overly filled with hubris, I’ll take the credit for that!Improving the intervention

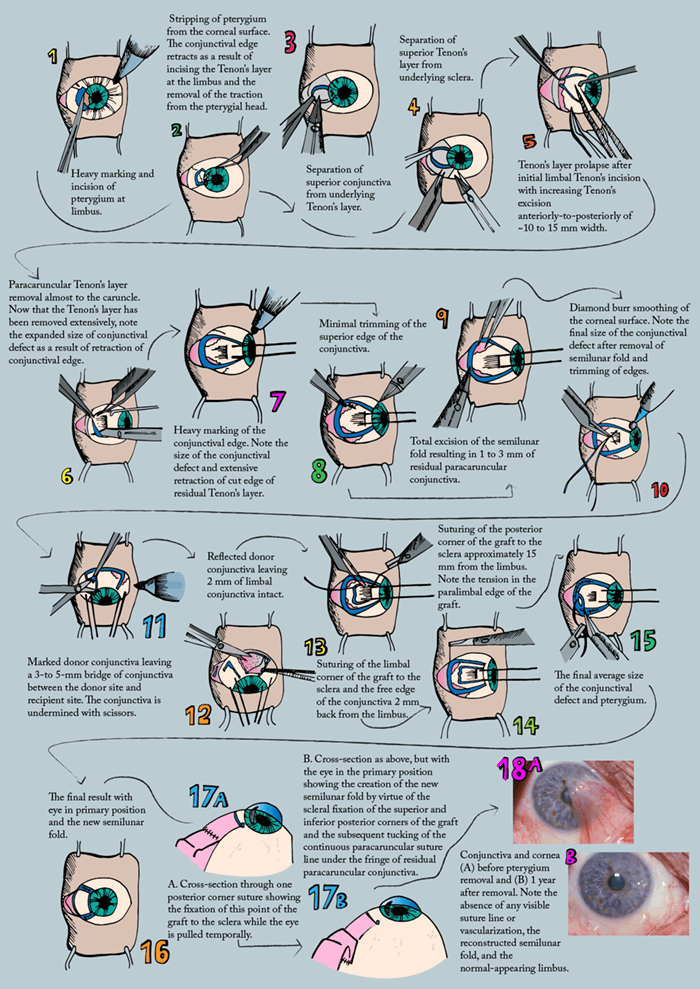

Conjunctival autografting – the removal of pterygium and placing a small piece of conjunctiva from elsewhere is an old technique, but it was brought to prominence in 1985 by an article from a former mentor of mine in the US (6). It’s turned out to be the gold standard for the treatment of pterygium. But, in the meantime, many of the people who previously used the quick, simple and dirty method of scraping and referring the patient for radiotherapy, started using the equally (in my opinion) quick and dirty method of scraping and using mitomycin drops instead. I decided to investigate whether there was a better method. I hit many dead ends; I tried other chemo drops and tried various other approaches, and finally decided that conjunctival grafting was the way to go. But I was still seeing recurrence rates of between 5 and 15 percent, which I thought was unsatisfactory. Additionally, I soon realized that patients wanted good cosmetic results as well. Most of the small grafts being prepared did not result in good cosmesis, with visible (and rather ugly) scars all the way around the graft. Joaquim Barraquer had hypothesized 30 years beforehand that the reason pterygia came back was because of the activation of Tenon’s layer – and that the removal of Tenon’s layer would reduce the recurrence rate after pterygium removal. I decided that he was probably correct, so I started removing more and more Tenon’s around the medial rectus muscle. As soon as I started doing that, the defect in conjunctiva grew and grew, because it turns out that the Tenon’s drags the conjunctiva onto the cornea. If you just section the pterygium at the limbus, you already get a sizable defect in the conjunctiva over the sclera. But if you then perform an extensive removal of Tenon’s as well, you get a quite huge defect in the conjunctiva – which goes back to the position where it had come from. As I was making increasingly large conjunctival defects, I ended up putting in larger and larger grafts. And that was the start P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM® (pterygium extended removal followed by extended conjunctival transplantation; Box 2 (7)).- Derived from the Greek Word “Pterygos”, meaning “small wing”

- It manifests as a wing-shaped fleshy band of fibrovascular tissue growth over the cornea

- It may disturb vision

- The closer you get to the equator, the greater its prevalence

- Men are twice as likely to develop it as women

- We believe that wearing sunglasses should help to prevent it

Box 2. The P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM®.

P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM® is a registered trademark to The Australian Pterygium Centre.

It’s got to be perfect

When I started performing this procedure, the recurrence rate dropped remarkably (8). But I still wasn’t entirely happy with the cosmetic appearance. It was pretty good – if you have bare sclera and put conjunctiva down and suture it to bare, Tenon’s-free sclera (and to any edges of existing conjunctiva) the resulting scar is almost invisible. So when I suture a graft in, you won’t be able to identify where it has been sutured to the existing conjunctiva after a few months – except for the region where the conjunctiva was sutured to the other free edges of conjunctiva that aren’t tacked down to the sclera. I’ve always found the nasal edge of the scar near the caruncle to be a problem – so the next step was to excise the semilunar fold and create a new semilunar fold that was able to hide the scar that always occurs when you suture conjunctiva to conjunctiva (7). I also realized, adding further finesse to the procedure, that if you took a very thin graft from the top part of the eye – so good, so thin, with virtually no adherent Tenon’s, that there was no bleeding from the underlying Tenon’s – it epithelialized very quickly, and within a few months you couldn’t tell that the graft had been taken. In fact, within six to 12 months, you can harvest a second graft from the same site.Perfection proves problematic

However, P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM® isn’t perfect. Despite the superb cosmesis and fantastically low recurrence rates, it has a major problem. It’s not an easy procedure to perform, and because it’s difficult, it can take a long time. Most people who just scrape the pterygium can do it in five minutes in their office. Even those that go into the operating room and perform a graft take at most 20 to 30 minutes to perform it. Routinely, this procedure takes an hour to perform, thanks to the fact that it is meticulous surgery with a focus on dissection planes. The other factors to consider are that you need an assistant – and that’s an added expense that nobody else has – and you need to give the patient peribulbular anesthesia (other methods just see surgeons injecting a bit of anesthetic underneath the pterygium). However, the advantages continue to stack up; for example, when done properly, patients experience less pain after surgery. In my fashion of wishing to investigate further, I followed a thousand consecutive patients – 99 percent for more than a year – and found just one recurrence (8) – that’s two orders of magnitude better than most other recurrence rates. I’ve also performed cosmetic studies to look at whether it’s possible for people to identify that a pterygium was removed from the eye. It turned out that it wasn’t possible – the cosmetic result was so good. I’m currently trying to follow people who received my P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM® surgery more than a decade ago, to make sure that my 10 year results follow my one year results.It was a very telling finding. The thinner the graft and the more immaculate you leave the Tenon’s from the graft retrieval area, the better the graft is and the more quickly it integrates when it’s transferred over into the pterygium site. And that, in short, is the essence of P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM®. For many years, I was a corneal surgeon, and had the largest corneal transplant practice in Australia. But about 10 years ago, the methods of transplantation changed fairly dramatically. To be frank, I did not wish to go through the learning curve that was required for these new methods (or to have my patients go through that learning curve either). At the same time, my pterygium practice was building up. I handed off my practice to someone else and took the risky step of only doing pterygium surgery. I was still doing this as CEO of the Queensland Eye Institute. But I wanted an identifiable place for this pterygium practice, so for the first time in my career, I went into private practice. It’s true that a practice lives or dies by referrals. It’s amazing how much word of mouth has built the pterygium surgery practice. Probably one in five of my patients are friends or relatives of people who have had the procedure done, and the rest are referrals from optometrists and general practitioners. I do maybe 300 pterygium surgeries a year – a third to a half of all pterygium surgeries in Queensland – and yet I probably get fewer than about 10 patients referred by other ophthalmologists, who continue to do their own. This is also fairly telling for a condition that they don’t particularly care to treat, and which they treat trivially: they’re not prepared to pass them on to someone who’s made it their life’s practice.

Now, I really do not want to keep this method of pterygium removal as a personal procedure. I would like to train others, but it’s a difficult technique that requires a mini-fellowship with me. I have been almost universally unsuccessful in this regard. I’ve managed to train one other surgeon in Brisbane and one in Townsville, who can do it as well as me. But that’s it. My synopsis? It’s very sad and discouraging. We now have a gold-standard method with more scientific proof of any other method, and yet doctors are not prepared to embrace it on behalf of their patients and themselves. One upshot is that I’m getting increasing numbers of patients to my pterygium-only practice... Every year, I go to the largest meeting in the US – the American Academy of Ophthalmology – and for about 11 years, I’ve been trying to teach my method. The problem is, you can’t learn this method from a lecture or a workshop; you can only learn it by actually sitting down with the person who developed it. And therein lies another issue: obtaining professional registration for foreign doctors so they can actually do surgery with me in Australia is a heinous procedure – it’s more difficult than the surgery!

- Pterygium is characterized by these basic elements:

- Epithelial covering of atrophic conjunctiva

- Degenerated, thickened, hypertrophied connective tissue that contains abnormal collagen

- Neovascularization, with vessels dispersed among the collagen fibers

- Hyperemic episcleral bed beneath the pterygium

- Tenon’s capsule is incorporated into the body – and contributes to its vasculature and bulk

And so I’m trying to do the reverse. A Canadian ophthalmologist who came to Australia for a week to watch me perform this procedure was so impressed that he wanted to learn it. After 12 months of correspondence and thousands of dollars, I spent three days in Saskatoon assisting this ophthalmologist in the learning phase. It’s more interest than I’ve received from Australian ophthalmologists who could come and work with me without any of these issues and difficulties. Consider this article an open invite. If you treat patients with pterygium, and you want to do the best for them – in terms of both cosmesis and avoiding recurrence, you should set your sights on P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM®. If you’re interested enough to learn, I’m more than happy to show you how. Lawrence Hirst is a pioneer of multiple ocular surgical techniques, including corneoscleral grafts and novel approaches for using tissue adhesive in perforated eyes. He developed the P.E.R.F.E.C.T. for PTERYGIUM® surgical technique and now performs pterygium surgery exclusively at the Australian Pterygium Centre, in Graceville, Queensland, Australia and in North Sydney as well. He can be contacted at lawrie@tapc.net.au.

References

- JC Hill, R Maske, “Pathogenesis of Pterygium”, Eye, 3, 218–226 (1989). PMID: 2695353. J Chui et al., “Ophthalmic Pterygium. A Stem Cell Disorder with Premalignant Features”, Am J Pathol, 178, 817–827 (2011). PMID: 21281814. JS Ambler, LW Hirst, CV Clarke, AC Green, “The Nambour Study of Ocular Disease 1. Design, study population and methodology”, Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 2, 137–144 (1995). PMID: 8963917. A Sebban, LW Hirst, Pterygium recurrence rate at the Princess Alexandra Hospital. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol, 19, 203–206 (1993). PMID: 1958364. LW Hirst, A Sebban, D Chant, “Pterygium recurrence time”, Ophthalmology, 101, 755–758 (1994). PMID: 8152771. KR Kenyon et al, “Conjunctival autograft transplantation for advanced and recurrent pterygium”, Ophthalmology, 92, 1461–1470 (1991). PMID: 4080320. RA Weise et al., “Conjunctival transplantation. Autologous and homologous grafts”, Arch Ophthalmol, 103, 1736–1740 (1985). PMID: 3904687. LW Hirst, “Prospective study of primary pterygium surgery using pterygium extended removal followed by extended conjunctival transplantation”, Ophthalmology, 115, 1663–1672 (2008). PMID: 18555531. LW Hirst, “Recurrence and complications after 1,000 surgeries using pterygium extended removal followed by extended conjunctival transplant”, Ophthalmology, 119, 2205–2210 (2012). PMID: 22892149.