Günther Grabner had a stellar career in ophthalmology. He founded Austria’s first Eye Bank in 1977 in Vienna and was a pioneer in corneal refractive surgery from the early 1980s. His work has spanned uveitis, presbyopia treatments with lasers, inlays and intraocular lenses, kerato-prosthesis surgery, glaucoma surgery and large epidemiological studies. If you’ve ever heard of the Salzburg Reading Desk – a system that precisely measures near visual acuity performance, that’s his too. He’s sat on many industry advisory panels, journal editorial advisory boards, and has held high office in many international ophthalmological organizations. Today, you’re still likely to find him in an academic setting – but not necessarily at the Eye Clinic of the Paracelsus Medical University in Salzburg. In his retirement, you’re more likely to find him in a lecture theater with his fellow Archaeology undergraduate students – or perhaps performing field work at an archaeological dig.

How did you transition from ophthalmology to archaeology?

That was easy: my father-in-law was a very prominent Austrian prehistorian for over half a century. He was Chairman of the Institute of Prehistory, and for many years, Dean of the University of Vienna. He started in the 1920s and retired in the late 1970s, but worked daily in the field until his death in 1985. Back in 1975, when I was engaged to his daughter (we married in 1976 and now have great fun with our first grandchild, Maria) I went to his lectures and truly enjoyed them. I had always been interested in archaeology (and later, in prehistory), and I’ve visited many sites in Greece, Turkey, Italy and Egypt over the years. In fact, I’ve probably seen most of the relevant southern European archaeological sites from Spain to Lebanon during my life – and I became so interested in the subject that I wanted to study it properly and just followed my interest… Second to eye surgery (which was the greatest passion of my life), this has always been a “hobby”, never “work”, and it has been quite a blessing…Did you find time to pursue your interest in archaeology alongside work?

No. Until I officially retired as a Chair of the University Clinic about two years ago, I really didn’t have the time. But my senior co-workers – they have become very dear friends over many years – gave me a wonderful farewell gift: two weeks’ “digging” vacation with the Salzburg archaeologists on the Greek Island of Aegina, near Athens. There, I spent time at an excavation site that had been going on for about half a century – always run by the Salzburg academics. I enjoyed it a lot. In September 2016, I decided to study prehistory in earnest and started to go to the University of Vienna to take classes and pass exams; in fact, I go to the lectures at the very Institute that my father-in-law had chaired. It was quite a change – but it feels easy because I’m still seeing patients in my two offices – in Vienna and Salzburg – once a week in each, and still doing surgery at both locations in private hospitals, so I haven’t completely left ophthalmology; it’s rather a smooth transition. I’m still going to some of the large international (and some local) meetings and giving some instructional courses, so I keep busy – but I’m hoping to pass these duties along to my younger colleagues very soon! However, as I was in charge of a large specialized clinic with more than a hundred co-workers, I definitely feel “retired”, that is, under-challenged! Last year, I had the pleasure of visiting Beirut. I was amazed how the country can get along and cope with these huge numbers of refugees – but life seemed to go on quite normal, although there were only very few tourists around! The Lebanese colleagues were very kind to arrange a visit to Baalbek. This site is located in Hamas country, so they thought the trip a little bit risky (basically, there were no tourists there!), but it was a great experience. The guide was a lawyer, and she took me in her private car, showing me around these wonderful, enormous Roman temples – even bigger than the ones in Rome – set in the middle of the beautiful Beqaa Valley countryside.

What do you miss about your old life?

Before retirement, I had the opportunity to see all the patients in the Salzburg Eye Clinic that were considered “difficult cases” with my colleagues and then we tried to find good surgical or “conservative” solutions, such as keratoprostheses of different types (we were the referral center in Austria). I really miss these “challenging” cases. Each day, patients with severe traumata to the eye, very young children with congenital cataracts, challenging cataract cases, acid burns (of which I saw a lot), and sometimes even patients requiring keratoprostheses (KPro) would come in. This can take a lot of your time (up to four hours, a minimum of twice or sometimes even three times to restore vision in one eye) e.g. for osteo-odonto-KPro which I learned to perform from my dear teacher Giancarlo Falcinelli in Rome. In Austria, you usually do not see such patients after retirement in a government-funded position, because you require a specialized clinic with some rarely used equipment to do the procedure. Routine cataract surgery, in general, is not really a surgical challenge for me, but “rebuilding” severely injured corneas? That was a privilege and I still miss it greatly. Now I mostly see patients that I’ve known for quite some years and with whom I have built up a relationship. They like to chat with me and they still come in for surgery, but it’s not the great daily challenge that I was used to and loved.Are you filling that challenge gap with your pursuit of archaeology?

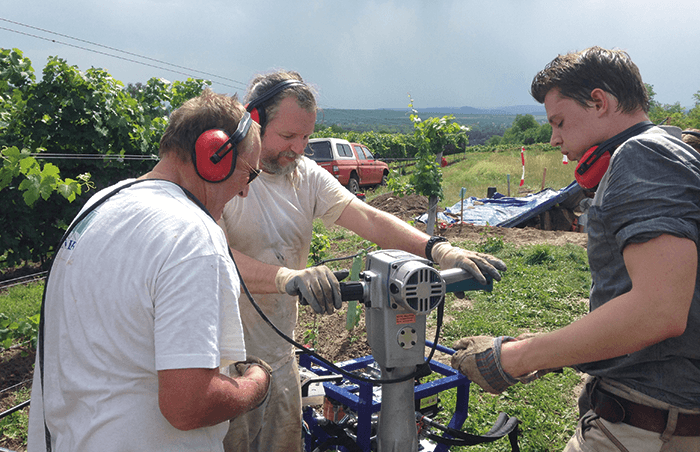

Well, it’s a completely different challenge! The first challenge is that I’m three times older than the 19–21-year old students on my first course – I’m old enough to be their grandfather! In fact, most of the professors at the Institute knew my father-in-law, because he was their teacher. Indeed, I’m also older than all of the teachers, which is another “mental” challenge... I’ve read a lot about archaeology over the years and keep asking questions in the lectures. In geophysical prospection, we study modern techniques of research and surveying, such as ground-penetrating radar, LIDAR laser scanners and magnetometry. This subject matter in itself is very interesting, but it’s the final payoff of identifying large areas of “no digging required” is what counts! The real difficulty is getting back into the habit of studying really hard! I haven’t tried to learn a book or article by heart for over 40 years! When studying medicine, to learn a book within a fortnight, was possible, but it’s a skill that gets lost with age; you have to retrain your brain… There are so many sites of prehistoric findings – several hundred important ones in Austria alone, and many thousands worldwide – that one should probably be aware of! In other words, there is no shortage of archaeological challenges!How are your interactions with the much younger students?

I think I’m well accepted; I treat them like colleagues, and they do the same. At first, they were amazed to have a student at my age (when I first entered the lecture hall, all were really quiet – probably thought I was the Prof…), but they’ve accepted it by now. Out of about 50 students in the class, I’m the only one in this age group, but it’s fun! We go to seminars and on field trips together. For example, there are some Paleolithic sites close to Vienna (you might have heard of the famous “Venus of Willendorf”), and we go on excursions – six students, two lecturers and two professors – and we take pictures and do some actual digging. We also learn how to dig properly, and how to handle what is discovered.