Credit: All images courtesy of Stuart Sondheimer

Credit: All images courtesy of Stuart Sondheimer

Could you talk about your career so far?

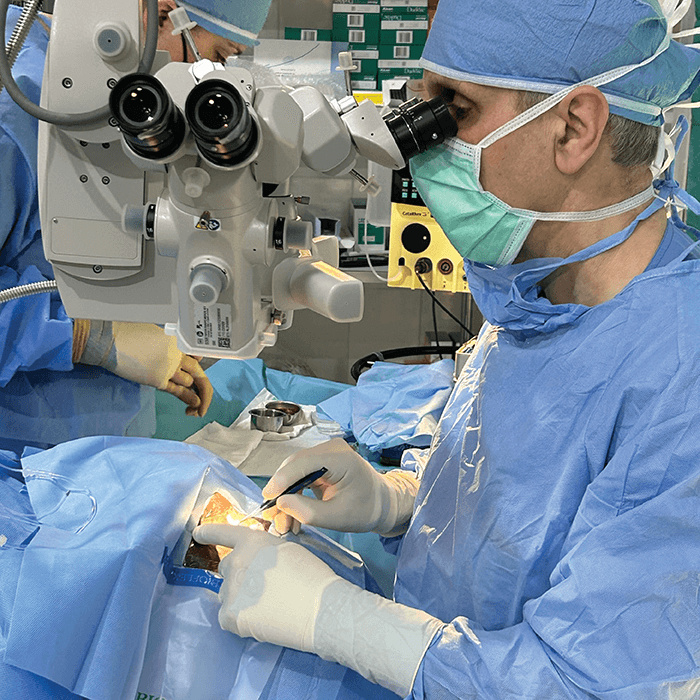

I was one of the first ophthalmologists in the US to offer surgical correction for myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism. I’ve performed more than 12,000 refractive surgery procedures and over 10,000 cataract surgeries, and I have taught other practicing ophthalmologists, residents, and medical students in the US and abroad.

In addition to performing vision correction and cataract surgery on other physicians, I’ve corrected the vision of several of my family members. And having had vision correction surgery myself, I can understand LASIK from the patient’s perspective.

Have any mentors helped you along the way?

Many wonderful mentors have inspired me, including Charles Casebeer, who helped get me started as a refractive surgeon, Robert Osher, who helped me become a better cataract surgeon, and Diego Mejia, who taught me modern SICS extracapsular surgery.

What sparked your interest in the humanitarian aspects of ophthalmology?

I met ophthalmologists who were traveling to underserved areas to perform surgery and was impressed that I could make a difference and have these fulfilling experiences. Over 30 years ago, I started traveling to Indian reservations and other remote areas in Arizona, treating patients with the Arizona Mobile Eye Unit. Over the last 11 years, as a volunteer eye surgeon, I’ve traveled to Vietnam, Honduras, El Salvador, Panama, and Guinea – seeing patients, performing cataract and pterygium surgery, and teaching.

What have been some of the highlights of your travels?

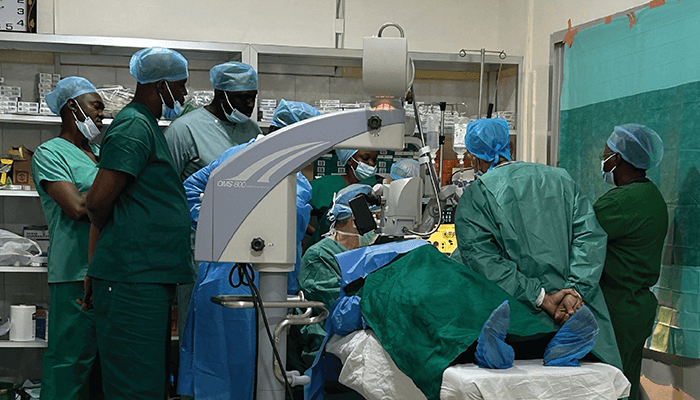

I’ve seen amazing places that I would never have visited without going on eye surgery missions. I’ve learned so much about life and ophthalmology, and formed deep friendships and partnerships with host ophthalmologists. I teach them about our advanced technology, and they teach me how to practice effectively with different resources. I’ve been touched by the people I’ve worked with and the people I’ve helped. I have gotten far more out of this work than I have put in. When I return from a mission, I’m not the same person I was when I left. And working in less fortunate places has made me aware of our good fortune in the US – I better appreciate our wonderful equipment, abundant supplies, and excellent surgical facilities.

What challenges have you encountered working in such varied places?

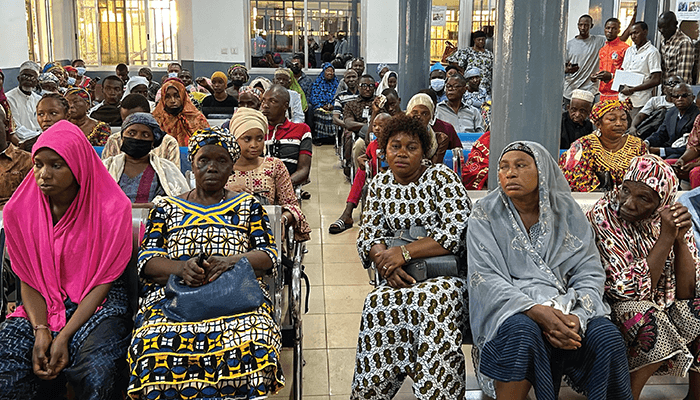

In remote areas in Arizona, logistical access to care was very difficult to provide. In Vietnam, the modernizing healthcare system is struggling to cope with high patient loads. In Honduras, El Salvador, Guinea, and Panama, many indigent patients can’t afford and don’t have access to cataract surgery and basic ophthalmic services. In all of these communities, it’s a challenge to provide modern surgical facilities and adequate supplies, and there’s a shortage of trained ophthalmologists to care for large segments of these societies. Operating in these situations, I’ve had to learn to successfully perform surgery with fewer resources, and subspecialist backup has often not been available.

What do you hope to see in regions with fewer resources in the future?

I hope we can train and supply physicians in medically underserved countries to provide better care, so that we are able to operate on more needlessly blind patients.

Are there particular programs, institutions or organizations you partner with?

I’ve partnered with wonderful charitable organizations: SEE International, Vision Outreach International, Combat Blindness Foundation, and FOCUS. These organizations connect volunteer ophthalmologists from the US and Canada with worthy colleagues in the developing world. They provide donated supplies and equipment for international missions. They help to train US and Canadian ophthalmologists to perform small incision extracapsular surgery (SICS), and train ophthalmologists in developing countries to perform modern phacoemulsification cataract surgery.

What more can be done to help these countries?

The wider ophthalmology community can support the development of healthcare infrastructure in the developing world by interacting with physicians, sharing educational opportunities, and donating equipment, supplies and expertise. The first step is to go to other countries and learn about what might be needed. Physicians in developing countries should be aided and empowered to create their own solutions to reduce treatable blindness. American and Canadian ophthalmologists can’t meaningfully address the millions of treatable blind patients, but we can empower others to provide more restoration of vision.