- Taking an idea and turning it into reality can be an incredibly long and arduous journey

- There are a number of pitfalls you need to avoid – IP, finance and competitors

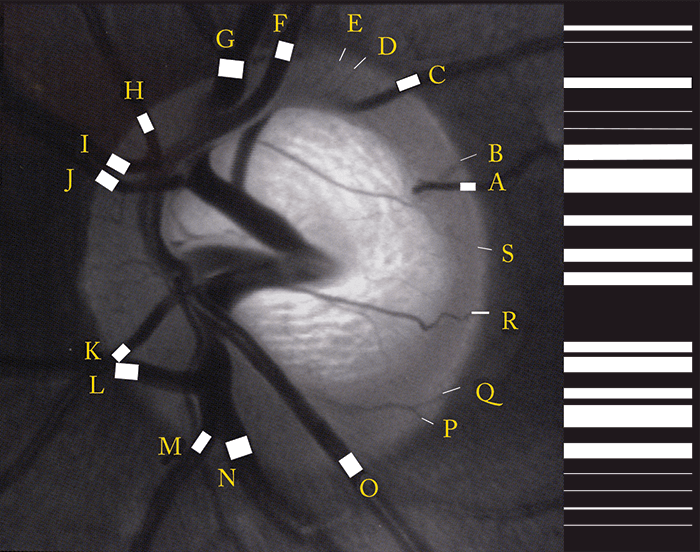

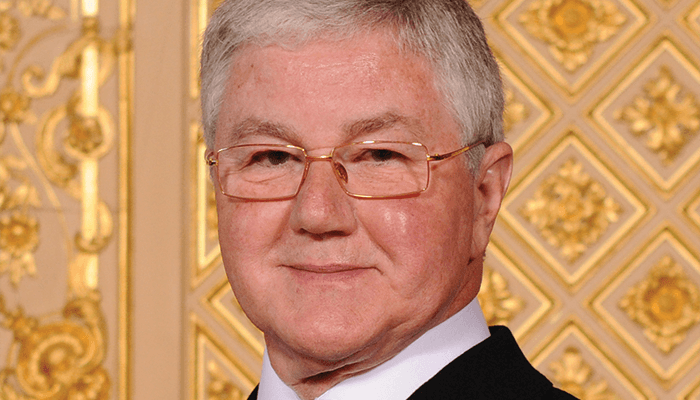

- John Marshall has invented and pioneered many technologies in eyecare and beyond – he’s far more than the inventor of the excimer laser

- Here, he shares his insights and his stories of innovation

If you work in eyecare, it’s almost certain that you already know of John Marshall – his reputation precedes him. John is many things: educator, mentor, academic, entrepreneur and most definitely, a serial innovator. He’s accumulated a great deal of knowledge and experience of innovation over his career – so that’s precisely what we asked him about.