My early 40s were such a busy period in my life; I seemed to be working all the time. I joined a high-volume practice with a demanding surgical schedule. Occasionally, I would have a headache, a tight jaw, some neck pain, or a back spasm over the years, but I took anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen or paracetamol and it always went away. Sometimes, if I reached for something in an awkward way, I would get a painful muscle spasm in my back which could last for a few days. The symptoms always went away and then I would forget all about it the next day.

After seven years of high-volume, fast-paced private practice, I made a career move to join an academic referral center. It was slow in the beginning and I noticed that I wasn’t having any back spasms. A few symptom-free years passed until my practice grew and I became much busier with lots of complex surgery and thus, more stress on my body. Then, I began noticing a fine tingling sensation in my thumb and pinky finger in my nondominant hand that would come and go. It was a psychologically terrifying feeling; alarm bells started ringing so I reached out for help.

First steps

I asked my ophthalmology colleagues about it and they suggested it was a cervical spine problem. What’s more, it seemed like everyone I spoke to had some experience of musculoskeletal issues: carpal tunnel syndrome, slipped discs… Some even had surgery. I realized that if I lost some function of my arm, my surgical career could be over, and I was determined to never let that happen.

I needed a plan. I went to a neurologist who advised me to get an MRI scan of my cervical spine – she was convinced that it was a disc herniation. After ruling that out, she prescribed physical therapy, which was very painful at first but worked wonders. At the first evaluation, I learned so much about my own body. I had never realized that my neck and upper back muscles were so tight that they restricted my range of motion and that the rest of the opposing muscles were so weak! I realized that my constellation of symptoms may have been related to work ergonomics. Was it a coincidence that my headaches, tight jaw, neck pain, and limited range of motion were all on my left side? I started to wonder if all of this was related. I had to consider why this was happening to me. No amount of physical therapy could work long-term if I didn’t address the underlying issue… and that issue is the physicality of how I practice ophthalmology.

Learning… to unlearn

Musculoskeletal disorders tend to sneak up on people, often without them realizing what is happening. As ophthalmology residents, we are taught to take care of the patient so we never really think about ourselves. Residents are not shown what posture to assume when examining or operating; the focus is on performing optimally for patients. There has to be a way to teach young ophthalmologists how to take care of themselves while they treat their patients. Ophthalmologists in training learn to contort themselves to get the job done right, and because they’re young, they don’t really complain or notice any adverse effects.

Young practitioners are not as busy, but as time goes by and they gain experience and reputation, their practice gets busier and the volume of work steadily increases… and they just keep working. By then, they have already established their muscle memory for most repetitive tasks, and they perform their duties mostly in the same, set postures.

Suddenly, surgeons find themselves 15, 20, or 25 years down the line, with a busy successful practice and they continue to perform their repetitive tasks with seemingly random musculoskeletal problems that they attribute to their age alone. Perhaps their back hurts, or they have a stiff neck, or their joints start aching? Often, we try to assign a specific event that triggered the symptoms without considering the impact of ophthalmic practice on our bodies. We take some anti-inflammatories, possibly muscle relaxers, maybe get a massage, and get straight back to work, to do the same repetitive tasks with the same poor postures.

My experience and personal plan

This is exactly what happened to me. With a busy, successful surgical practice, I operated for many hours a day and disregarded my initial neck and back symptoms. When I started noticing them more frequently, I changed to a prevention mode: I avoided bending in awkward ways, and I was careful about the way I made sudden movements. For some reason, I never considered that my symptoms could be related to my job. By the time this realization came, I was so far down the slippery slope – 20 years, no less – that it has become an issue quite difficult to fix. How do you unlearn 20 years’ worth of work-related bad habits and reposition yourself to do something that you have done thousands of times differently?

I began my re-education and started re-learning all my everyday work tasks in a new way, which was hard because the old way was second nature.

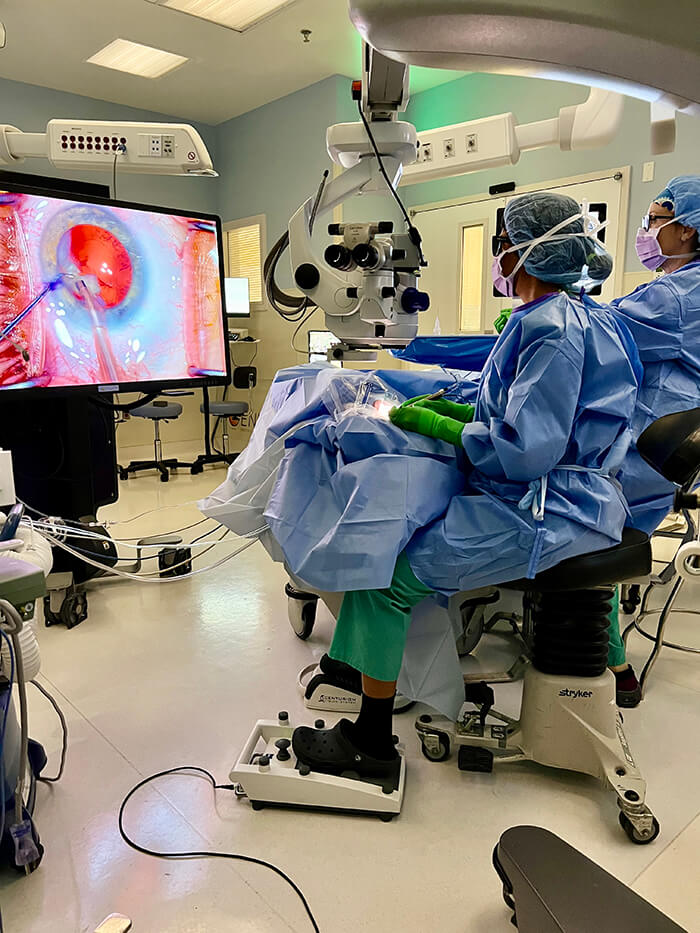

First, I invited my physical therapist to the OR with me to observe me operate. She gave me feedback regarding better posture and recommended specific stretches between cases. I then changed some of my work equipment that would help me change my posture. In my office, I added an angled adaptor attachment to my slit lamp oculars which forces me to use a head-down tilt posture as I examine patients. In the operating room, I started using a 3D heads-up display so I’m not forced to bend forward and extend my neck to look into the oculars. I also now use a wrist rest and take extra time to position myself at the beginning of each case and check that everything is in a comfortable position before bringing the patient into the mix. I understand that I might be able to do this 80 percent of the time, then schedule the extreme kyphotic patients who require me to use uncomfortable posture for surgical access sporadically. Performing the PT stretches between cases and at the end of the day is key. I’m hoping that with these modifications, over time my symptoms will gradually go away so I can increase my surgical longevity.

The next generation

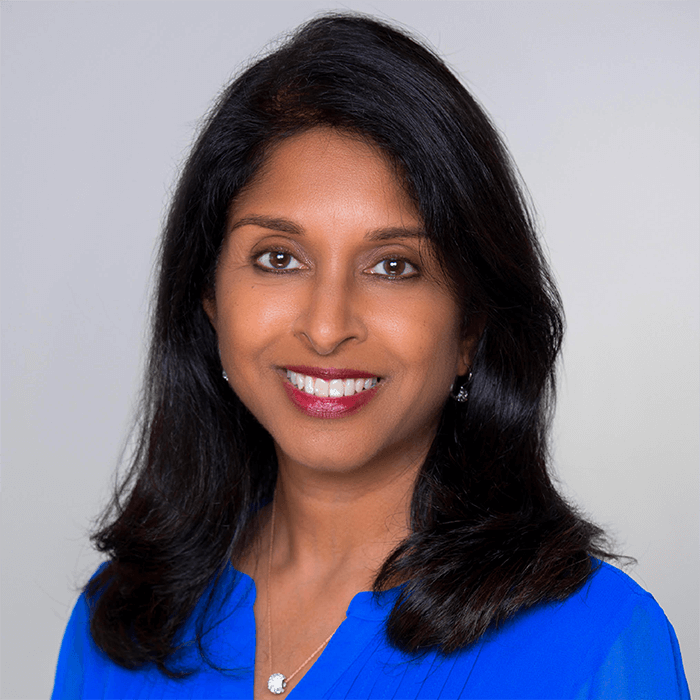

As I learned more and more about the importance of ergonomics, I decided to share my personal story so it may help residents and colleagues before they encounter musculoskeletal problems. I hope to do something not just for me, but also for the future generations of ophthalmologists. I am currently conducting ergonomics research projects with medical students and residents at Westchester Medical Center in Valhalla, New York, US. We hope to shed light on the problem and provide innovative solutions.

Residents should start ergonomics education at the beginning of their careers. While they are learning the anatomy of the eye, they should also learn what posture to take to conduct an exam or a procedure. The hope is this will help them have a longer career and deal with fewer aches and pains. We are currently introducing these important topics into the curriculum for our ophthalmology residents at New York Medical College and hope that other programs will follow suit.

For mid-career surgeons, I encourage you to have open discussions with your colleagues about any musculoskeletal symptoms you’re having and you’ll find that you are in good company. You may ask, what can be done? We can try to undo the damage done by years of poor posture. We have the tools available to us – whether it’s new equipment or specific exercises – and we need to use them now. In part two of this series, I will discuss how the slit lamp adaptor, 3D heads up scope, surgical wrist rest, exercise and stretching have worked for me and the changes I've observed.