Since that “one small step,” mankind has made giant leaps forward in space science. Today, astronauts regularly check in and out of the International Space Station (ISS), and the time they spend there is becoming longer and longer. But extended spaceflight brings with it a specter: visual impairment due to intracranial pressure (VIIP) syndrome, giving space agencies another vital mission… to characterize the syndrome and to figure out how to protect their astronauts from it.

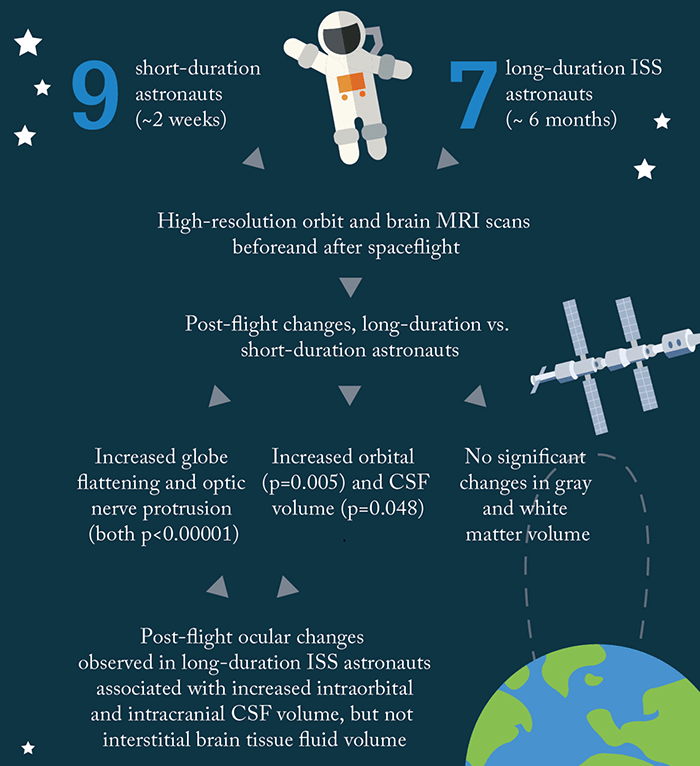

Associated with globe flattening, hyperopic shift, choroidal folds, and optic disc edema, VIIP is thought to result from microgravity-induced cephalad vascular fluid shift, with symptoms being reported by up to two-thirds of astronauts during or after space flight (1), (2). But to date, the actual etiology of VIIP syndrome has not been defined. Now, a team from the University of Miami who have been studying ocular shape and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) volume changes in astronauts, have provided the first quantitative evidence for a direct role of CSF in spaceflight-induced ocular changes (Figure 1)(3). Noam Alperin, Professor of Radiology and Biomedical Engineering at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, and lead author of the study, tells us more…

Why?

Our group has been investigating the CSF system for a long time, and we’d developed a method to measure intracranial pressure (ICP) non-invasively by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). In 2010, I received a call from NASA, “Miami, we have a problem.”How?

We installed a protocol in their MRI scanner that’s located near the Houston space center. For four years, we studied astronauts before and after space flights, collecting data from short-duration and long-duration astronauts. The algorithm we’ve developed to assess morphological changes provides a quantitative measure, and is much more accurate, reliable and reproducible than previous methods which involved “eyeballing the eyeball.”When?

We saw that most astronauts developed VIIP to a certain severity by six months. From studying short-duration astronauts who have been in spaceflight for two weeks, we know that VIIP starts after a much longer duration than this – I would say after several months of time in space and we expect that the longer the flight, the worse the deformations.What’s next?

We’re already starting to use our approach to study glaucoma, and we’ve done a lot of work that will hopefully be published soon. We think our method of measuring CSF volume is a consistent way to assess the balance between the eye and the brain. We’ll also continue working with NASA to examine the effects of “head down tilt” on the globe. In this study, subjects will spend 30 days in bed with a head-down tilt of six degrees to simulate the movement of fluids from the legs to the head, and we’ll measure and quantify the deformation that occurs.References

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Human Research Program, Human Health Countermeasures Element, “Evidence Report: Risk of spaceflight-induced intracranial hypertension and vision alterations”, July 12, 2012. Available at: http://go.nasa.gov/2hi867z. Accessed December 13, 2016. TH Mader et al., “Optic disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, and hyperopic shifts observed in astronauts after long-duration space flight”, Ophthalmol, 118, 2058–2069 (2011). PMID: 21849212. N Alperin et al., “Role of cerebrospinal fluid in spaceflight-induced visual impairment and ocular changes”. Presented at the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) annual meeting, Chicago, November 28, 2016. Presentation # SSC11-04.