- For students and young physicians, mentorship is an essential component of professional development

- The relationship can take many forms, including group and peer learning, or mentorship from afar, but the traditional one-on-one model can often have the most impact

- Institutions should offer different options to meet different learning styles and individual backgrounds

- A negative mentoring experience can be disheartening, but identifying a good match and building trust can be a formative experience that lasts a lifetime

In medicine, mentoring is an essential part of professional development. With the advent of the Internet, it’s very easy for students and young doctors to find factual information and medical knowledge online from various sources, without necessarily needing to be taught in the same way as they would before. But there are still some things you can’t learn that way: how to conduct yourself professionally; the best way to interact with patients; and how to succeed in your field. In a profession such as ours, there’s undoubtedly a set of behavioral skills that need to be transferred to a learner, and it really takes another individual, or group of individuals, to transfer that information. In turn, this motivates learners to develop to their full potential as physicians and surgeons, and when they look back and see what they’ve gained, they often want to pass that knowledge on to future generations. But not all mentorships are fruitful – there are considerations to bear in mind, and pitfalls to avoid…

The four key stages. Mentorship has four defined stages:

- Initiation - The mentee identifies a suitable mentor, or vice versa, and the relationship begins.

- Cultivation - The mentee is developing with the help of their mentor, and knowledge and skills are being transferred.

- Separation - This phase occurs when it becomes necessary to end the relationship, either because it's not working, or simply because it has run its course.

- Redefinition - Separation isn’t always the end of the story – the mentorship may carry on under another format. However, for the relationship to be successful, there needs to be an end, a separation, and then a redefinition. This is a common stage for things to go wrong. For example, instead of separating, the mentee can become more dependent: the mentee can’t do without their mentor, and fails to fly on their own. Mentor and mentee can continue to work together, but it’s important for the relationship to change in nature and be redefined.

Barriers and boundaries

There are several reasons why a mentorship program might not be successful (1). One simple but perhaps fairly common problem is that of scheduling – the mentor is perhaps incredibly busy, or simply not around when the mentee has time to see them, or vice versa. Then there are people who have difficulty establishing relationships, and who might find it difficult to open up in a one-on-one setting, and may be better suited to joining a group. It’s also very important to set boundaries – when a mentor and mentee meet, it is good to do so in the workplace. The moment the meetings start happening outside of work, you need to think about what this might mean, and whether it’s appropriate, say, to have that person over to your house, or if you’re moving beyond the scope of the mentor/mentee dynamic. Keeping the location neutral is often the most sensible choice. It’s also important to establish the goals of the relationship, or you risk finishing your mentorship without the desired outcome. For example, if I am working with a new resident who needs to learn how to do a retinal exam, I will state clearly: “During your time with me, I want you to become increasingly accurate and efficient at performing a retinal exam. You’re going to be working on this for the next 10 weeks, and this is how I would suggest you go about doing it.” Setting goals and then assessing them at the end of the training period is a great way to reflect on what you are actually achieving. When looking at individual mentors and mentees, there’s also the issue of differences – be they cultural, generational or gender-based. In my experience, there’s a lot of discussion in academic medicine around how best to match people of common interests, backgrounds or experiences in order to fulfill the institution’s mentorship mission, and that’s a good thing. For example, we have a Native American group at our institution, and this allows junior individuals to meet and learn from highly successful people in their field with a common cultural background. Another example is our women in medicine group. Having a portfolio of different mentors is very important when catering to a diverse group individuals – one option isnever enough!

Building trust

The final, and possibly one of the most crucial, parts of successful mentoring is building trust. In academic medicine, there are times when you are giving information and skills to people who might soon compete with you. This can be a major disincentive for people to transfer everything they know, and it’s something that isn’t often spoken about. But it all comes down to the relationship that people form – and building trust is huge. Mentors may think: “Well, if I give my time and my knowledge, I expect some recognition or gratitude for it”, because it’s generally uncompensated activity and effort. So when mentees don’t recognize their mentors, or don’t thank them, it puts people off. Likewise, when a mentor takes advantage of their mentees by not giving them credit for having done a certain amount of work, it has the same negative effect. But when the relationship is built on mutual trust and respect, the mentee will know that what they are gaining from the mentor is absolutely essential for their formation as a professional. In turn, the mentor will know that transferring this information is propagating the profession, and that the success of their mentee will also be a demonstration of their own success as an educator.It’s worth it

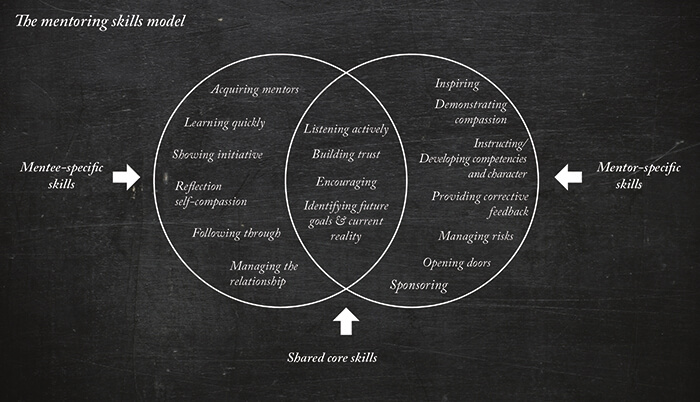

The mentoring skills model (Figure 1) outlines the skills that a mentee needs, the skills a mentor needs, and the common set of shared skills that they both need to build a successful mentorship relationship. Mentorship programs are common in the US, and can be found all over the world – but there can be hugely different interpersonal dynamics, depending on the culture at the institution involved, the needs of the individuals, and the support the institution is able to provide. Mentoring always has been, and always will be, an essential part of passing down medical knowledge from one generation to the next, and when it’s done right, it can be a hugely positive experience for everyone involved, junior or senior.References

- AR Gagliardi et al., "Exploring mentorship as a strategy to build capacity for knowledge translation research and practice: a scoping systematic review", Implement Sci. 25, 122 (2014). PMID: 25252966.