Ophthalmology is at the brink of change – one driven not by human hands, but by lines of binary code and algorithms. Yes, the era of artificial intelligence (AI) is upon us. And on whichever side of the AI fence you sit, the technology looks set to spread unceasingly across ophthalmology – just as it will across many other industries and society at large. As our 2024 Power Lister Ben LaHood (Adelaide Eye and Laser Centre) says, “We are going to see AI revolutionize ophthalmology to the same scale that the internet has changed our everyday lives. It will be everywhere and in everything we do as eye surgeons. Like all new technologies, there will be pros and cons of adoption, but just like the internet, there is no turning back now.”

LaHood may touch on the familiar sense of caution that surrounds the AI debate, but, make no mistake, he is excited about AI’s potential. “Ophthalmology is such a data-rich speciality that it lends itself to teaching systems to do almost all aspects of our work in a more accurate, safer, and more efficient manner,” he says. “As a refractive surgeon, I see AI becoming far better than me, for example, at determining the risk of ectasia and incorporating corneal shape into laser surgery treatments. Tasks that currently seem insurmountable, due to having too many interrelated variables, such as predicting surgically induced astigmatism, will become historical relics.”

Ben LaHood

OCT imaging and diagnostics

LaHood’s enthusiasm reflects the positive reactions we received from many of our 2024 Power List alumni when we asked them, “How do you think AI and machine learning will impact ophthalmology?”

Many are looking forward, for example, to AI’s impact on advancing the diagnostic potential of optical coherence tomography (OCT). Arthur Cummings of Wellington Eye Clinic, Dublin, anticipates that “much of our image-based work will be performed by AI, and it will likely be more accurate than what we did before,” with AI doing “a better job of detecting glaucoma progression from analyzing OCT images and visual fields.” Likewise, H. Burkhard Dick, of the University Eye Clinic Bochum, Germany, foresees the technology turning OCT and other diagnostic tools “into powerhouses for the detection of systemic diseases, such as arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus.” Moreover, it will “support, maybe even revolutionize, the diagnostics of diseases from other disciplines that have an impact on our patients, e.g., multiple sclerosis, dementia, Parkinson’s, and cardiological and endocrinological ailments.”

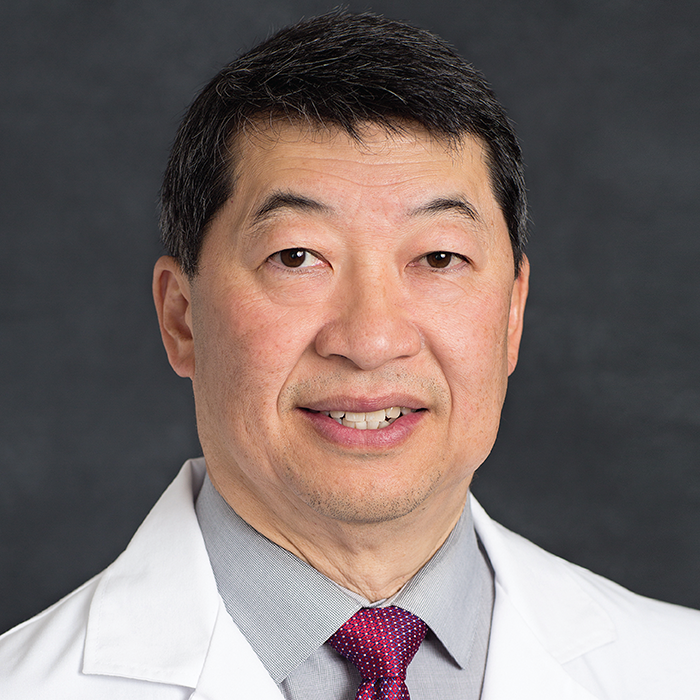

The Beijing Tongren Eye Center’s Ningli Wang positions AI as key to “achieving cellular-level resolution through OCT technology.” He explains, “The upcoming ‘OCT+X’ technologies, such as OCT combined with adaptive optics, Doppler imaging, and terahertz imaging, will push ophthalmic imaging to unprecedented levels of precision.”

And Christina Y. Weng of Cullen Eye Institute, Texas, adds that one of the most exciting applications of AI is “an emerging technology called home OCT.” She explains, “These AI-supported devices facilitate remote monitoring by allowing patients to self-capture daily retinal scans that could promote earlier disease detection and bring us one step closer to personalized medicine.”

I. Paul Singh of The Eye Centers of Racine and Kenosha, Wisconsin, USA, agrees that AI will not only allow for the earlier detection of diseases, such as retinopathy and glaucoma, but will also “help us to understand the progression of those diseases earlier than we can now.” AI, he goes on, “will help us to identify which patients will benefit from a particular therapy, which glaucoma technology or technique to use, which IOL to implant, or even which medication to utilize.” From a diagnostic perspective, Singh adds, “AI can help us to perform more accurate and targeted surgery.”

This progress, in turn, will bring diagnostics and disease monitoring to a much larger population, observes NHS England’s National Clinical Director for Eye Care, Louisa Wickham. “I think this could be of value globally, particularly in countries that may be able to afford the equipment but do not have the expertise to analyze the data. It could help to support disease prevention and early diagnosis and treatment in populations that currently have very low access to health care.” AI can enhance autonomous diagnostics relatively inexpensively, adds Wills Eye Hospital’s Joel S. Schuman, and this is key to enabling access to care in regions without adequate numbers of ophthalmologists and subspecialists.

H. Burkhard Dick

Christina Y. Weng

I. Paul Singh

Patient care and management

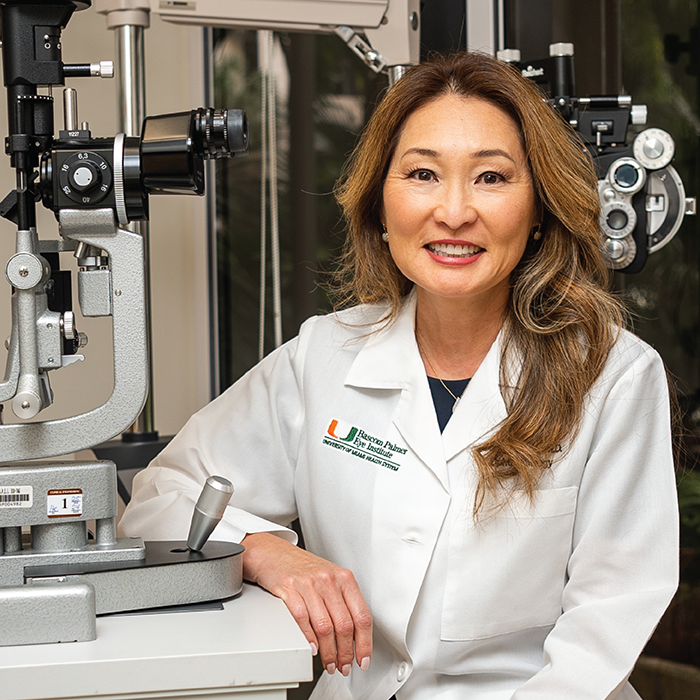

Of course, medicine involves not just diagnosis, but patient management. Sonia H. Yoo of Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Florida, looks forward to AI helping “decipher which patients should get which kinds of lens implants, identify which keratoconus patients to crosslink prior to them advancing, and see which patients need corneal transplant rejections and treat them accordingly.” Wills Eye Hospital’s Allen C. Ho believes AI can help to improve our understanding of vision loss in patients, which “will help us develop and provide better care.” The technology will be able to assist in “better selecting the best-fit IOL for an individual's lifestyle,” observes Arthur Cummings. Hopefully, adds David Lockington of the Tennent Institute of Ophthalmology, Scotland, “the machines will talk to the patient, talk to each each other, and then tell us which IOL is best for each individual patient’s needs and lifestyle, or which topical medications will best optimize the patient’s ocular surface based on bespoke molecular tear film analysis.”

The integration of generative AI with connected devices will lead to a “continuous feedback loop between patient data, machine learning (ML) models, and precision treatment strategies,” predicts Bascom Palmer’s Ranya Habash; this will facilitate “an ever-improving understanding of human health and, indeed, “could usher in a new age of medicine.”

As well as helping ophthalmologists provide better care for patients, AI will help to facilitate “large clinical studies on natural history and the benefits of treatment,” says Bascom Palmer’s Harry W. Flynn, Jnr. Further, it will “allow residents and fellows in training to improve their knowledge base, which will secondarily impact the quality of care of patients in the field of ophthalmology.”

Sonia H. Yoo

Allen C. Ho

Ranya Habash

The human touch

A more contentious area of AI in ophthalmology is the question of where the “human doctor” resides in this future landscape. Do you conjure up dystopian scenarios – with frantic ophthalmologists locked out of their practices, banging on the windows as the machines “take over?” Or is your AI-fueled world utopian, with doctors and machines working together in harmony to see that the practice runs extra smoothly?

Certainly, Christopher J. Rapuano of Wills Eye Hospital is hopeful that AI will reduce “many of the tedious tasks physicians need to do every day, such as writing progress notes.” Michael F. Chiang notes that, when AI becomes successful in assisting with real-world diagnosis, “clinical practice may shift toward management.” He explains, “This will involve detailed communication, empathy, and shared decision-making between patients and clinicians based on risk-benefit tradeoffs, personal values, and so on. I am concerned that clinicians are losing these nuanced skills in an era of electronic health records (EHRs), copy-paste, and text templates – we will need to do more to cultivate those skills in the future.”

For Chiang, then, the rise of AI could, ironically, help regain some of those “lost” human skills. Gus Gazzard of Moorfields Eye Hospital, London, agrees: faster, more accurate, diagnoses with less room for “in my opinion” will create an “ever greater need for simple communication and compassionate discussion about risk and prognosis with anxious patients.”

As for AI “replacing” surgeons, Allen Ho is looking forward to AI’s impact on “precision image-guided robotic surgery,” while Charles McGhee says boldly that he “fully expects robotic surgery will replace the cataract surgeon within a decade.” David Chang of the University of California, San Francisco is also “optimistic about the feasibility of fully autonomous robotic cataract surgery” – noting that “the hardware is already viable and workable” – but cautions that developing AI-powered, machine learning software “will be the main challenge for an autonomous cataract surgical robot.” That said, he notes that some industry experts are suggesting that the creation of such a system will be less challenging than creating fully autonomous vehicles. “The beauty is that robotic hardware and software can be scaled and duplicated much faster and for less cost than training and employing a comparable number of new cataract surgeons.”

But Chang goes on to say that cataract surgeons “will still be needed for more difficult cases and to supervise and monitor the autonomous systems.” Indeed, the notion that human ophthalmologists will need to stay at the forefront of the patient management landscape of the future is one that is widely shared by both those who are optimistic and those who are cautious about AI. “Personally, I believe that AI and ML will only serve to support the future of ophthalmology,” leading to “greater efficiency, more patients, and, ultimately, more sight saved,” says Stephanie Watson of the University of Sydney.

“AI will not revolutionize ophthalmology on its own,” notes Marie-José Tassignon of the University of Antwerp. “It needs ophthalmologists to guide the scientists involved in the development of AI. There is plenty of potential here, but how far we go depends on making the right choices; it is about defining how AI can best serve our specific needs in the field.”

Says Bascom Palmer’s Richard K. Parrish II: “The biggest value of AI and machine learning will be helping patients realize that care and humanity is a unique component of a doctor-patient relationship, not an abstract concept defined in cyberspace.”

Meanwhile, Advalia Vision’s Francesco Carones does not believe that AI will replace human relationships. He says, “I believe that direct interaction with patients – to try to understand their fears and desires, and the compromises they are willing to accept – will remain fundamental in helping them make the most appropriate choices.”

Michael F. Chiang

David F. Chang

Francesco Carones

Let there be light…

But perhaps we should give the last word to Pearse Keane. As well as being a consultant ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, Keane is Professor of Artificial Medical Intelligence at UCL. As such, he has been more deeply involved in the theory and application of AI and ophthalmology – and for a longer time – than many of his peers.

“The patient experience is profoundly rooted in human interaction with a clinician,” he agrees. “There is no replacement for an ophthalmologist when it comes to patient communication, nuanced decision-making, and in delivery of care such as surgery. The real power of AI in our profession lies in helping us tackle the challenge of growing waiting lists – by enabling more accurate triage and referral of patients at community level.”

And for Keane, another reason that we can afford to pause and take a more considered view of the coming of AI is that “we’re still in the 1870s,” when it comes to AI and healthcare. “I see parallels between where we are now and the dawn of the electrical age,” he explains. “The electrical age officially began on September 4, 1882, when the switch was flipped at Thomas Edison’s power station in lower Manhattan, providing electricity to households in New York. By the end of the month, Edison’s company had 59 customers; the next year, 513.” That moment in 1882 was “the culmination of 20 years of experimentation with more than 20 different prototype lightbulbs, but the bulb was only one small part of the story,” continues Keane. “Before the lightbulb could work, you needed a reliable source of electricity; a distribution system – i.e., the ‘grid;’ a connection system; and a measurement system. A network of innovations was needed before the lightbulb could be adopted as a viable, widespread alternative to candlelight.”

We need a similar supporting ecosystem in place to take advantage of the massive potential of AI in healthcare, says Keane. “That includes considerations such as integration with imaging devices and administrative systems, an effective and user-friendly interface with clinicians, having a viable business model, and a forward-looking regulatory system, which, in the case of AI as a medical device (AIaMD), is still evolving.”

If the current state of healthcare AI is, then, analogous to the dawn of the electrical age, we have a little bit of time to further illuminate the one-way road that lies ahead.

Pearse Keane