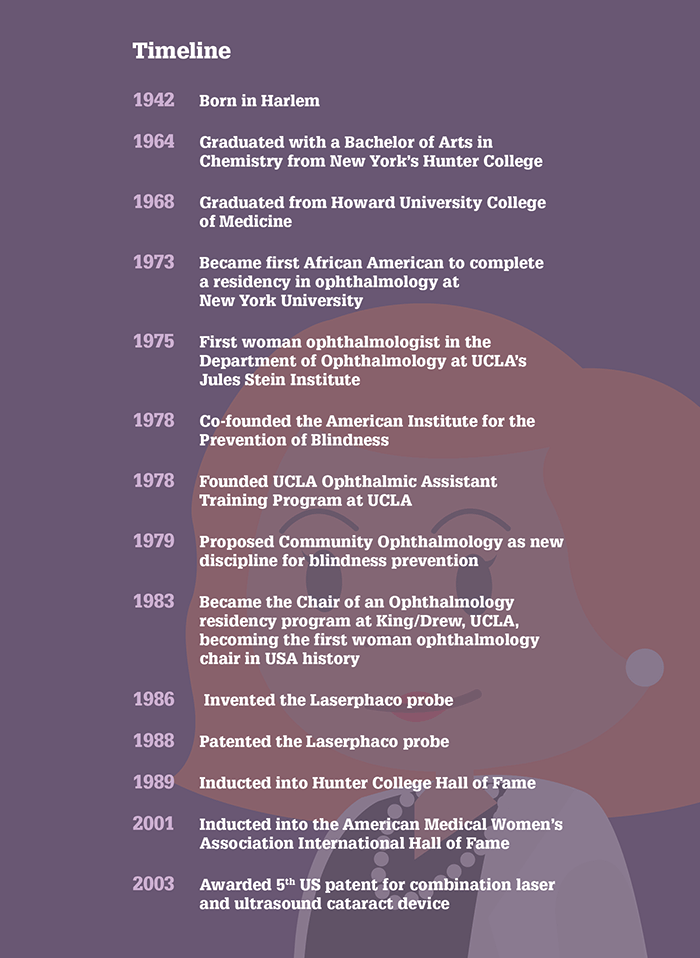

- Patricia Bath was the first African-American to become an ophthalmology resident, in 1973

- Later, in 1975, she became the first woman ophthalmologist at UCLA’s Jules Stein Institute

- Patricia is one of the pioneers of laser technology in cataract surgery, inventing the Laserphaco probe in 1986

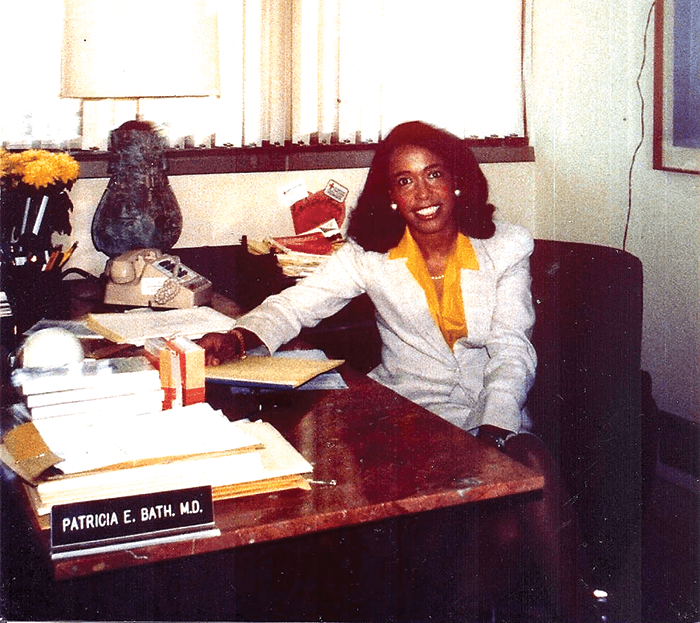

- In this interview, Patricia talks about her life, career and future aspirations

Born in Harlem, Manhattan in 1942, Patricia Bath is a dedicated ophthalmologist, inventor, and a lifelong campaigner for equality, breaking new ground for women and African-Americans in her field. Her long and successful career to date has seen her pioneer laser treatment of cataract, file multiple patents, and serve as Associate Professor of Ophthalmology at UCLA Department of Ophthalmology where she currently holds an Emeritus appointment on the medical staff. Here, she tells us how she did it and what she learned along the way.

Education and poverty

I was interested in a career in medicine since childhood. Growing up in Harlem, many people would have considered my family poor – but we didn’t apply that label to ourselves. My family taught me that I could achieve anything through a combination of hard work and education, and my brother and I were raised to believe we were unstoppable, unconquerable winners. We had such an intense work ethic that when I was awarded a scholarship at Hunter College in 1960 to study chemistry, we decided as a family that I didn’t need it. Admission to Hunter College was based on academic merit and test scores, and tuition was a mere few hundred dollars. Because of my father’s intense sense of pride, he looked upon the scholarship as charity and preferred to pay for my books and tuition. I recall the look of surprise when I met with the committee and advised them that I did not need the money. In today’s society there are those who would argue that I should have accepted it and spent it on luxury items, but my family had a simplistic, easy notion that if your clothes were clean and honestly obtained that you were okay. So from my perspective, I was rich, not poor. I carried this drive and motivation throughout my life.Ophthalmology inspiration

As a student, I was inspired to enter ophthalmology by an ophthalmologist I admired greatly, Lois A. Young. She was one of my medical school professors, and I admired her medical brilliance, swag, and character. She was so dedicated to her patients, students, and family – her love for humanity and joie de vivre was palpable. When I began my residency training at New York University, I had no idea that I was the first and only African-Americans ophthalmology resident. I did not know, or even care! But I did know that my superior grades, scores and credentials had earned me a coveted spot in a highly competitive residency, and that was awesome. I was happy and excited that I was about to capture my dream and become a great ophthalmologist by training in one of the most prestigious programs in the USA. We five first year residents functioned effectively as a team without any bias or acrimony, and there was more of a camaraderie fueled by our lowly status as first year residents at the bottom of the totem pole, than any discord from ethnic and cultural differences.Debating, designing and dancing

The biggest challenge I overcame in my career was wanting to do research, but not having the funding or a lab to do it in. When I encountered discrimination, I stayed focused on my goal and worked to outsmart the racism I faced – with ingenuity, rather than wasting my time and energy complaining about it. Taking the high road may be arduous and long, but it will lead to justice and triumph. When I failed to get grants for various research projects, I used my research talents to identify labs and like-minded scientists with a passion for discovery and invention. When I couldn’t get any grants to do my laser research in the USA, I looked for the best labs for laser research in the world, identified the principal investigators and nagged them until they agreed to provide access to their labs. First, I presented a hypothesis and well organized experimental plan, and I was willing to argue my case and debate the pros and cons. But I think I really succeeded because of a shared zeal to discover and invent, be a part of something new and adventurous, and shared adrenaline for chasing the high of that climatic eureka moment of discovery. So, like the explorer Columbus I sailed across the Atlantic and found a welcoming collegial atmosphere at the Loughborough Institute of Technology in England, the Rothschild Eye Institute in Paris and the Berlin Laser Medical Institute. I didn’t waste time with phone calls or petitions about the unfair and discriminatory practices of the National Institutes of Health or the National Eye Institute. Instead of worrying, I spent my time enjoying myself – thinking, designing and dancing.Patenting firsts

Historians have credited me as the first African American physician to receive a medical patent, but I prefer to be recognized simply as the first to develop and demonstrate Laserphaco, a laser cataract surgery technique. In the nomenclature of modern cataract surgery, we have evolved from the ultrasound era to the laser era. No one called ultrasound phaco “millisecond cataract surgery” or laser phaco “nanosecond cataract surgery.” YAG laser capsulotomy triggered the launch of the laser cataract surgery era. But in YAG laser capsulotomy the laser was deployed after removal of the cataract, and never during cataract surgery. When I introduced Laserphaco, the era of laser cataract surgery began – and has continued to advance and evolve with the introduction of new technology and equipment. The fact that cataract surgery is accomplished with femtosecond lasers changes the time metric, but the device is still a laser device, therefore it’s still Laserphaco, in my humble opinion. There were others before me and certainly there will be many others after me, but I am very grateful to be included among the pioneers of laser cataract surgery (1,2).Standing up for STEM

I’ve achieved so much in my career, and it’s important to me that I pass on the torch and help to inspire others to get involved in science, technology, engineering and medicine (STEM) – whatever their backgrounds or circumstances. I realize some of the slights, oversights and omissions I have experienced in my career are the result of systemic societal, gender and racial bias, and are not aimed at me personally. And realizing that you are not alone is empowering. A common denominator for discrimination against women and minorities has been the denial of voting rights. Accordingly, I have begun a campaign I call Suffragettes for Science. I want to champion the cause for all women in science like Rosalind Franklin, Ada Lovelace, Chien-Shiung Wu, and Lise Meitner, who did not receive their deserved level of recognition, respect and rank during their lifetimes. Being poor shouldn’t hold you back either – when I talk to disadvantaged school kids about poverty, I tell them that the label of “poor” is a tactical assault of naming and shaming. I tell children to “shake it off” à la Taylor Swift and believe in themselves. Repeat after me: I am a winner! I hope that through my past legacy and future advocacy, that the current and future generations of young scientists will not experience the hurtful wounds of discrimination of any kind.

Vision for all

My other lifelong passion is, of course, the prevention and cure of blindness, especially for underserved populations. On a personal level, each time I have restored or improved someone’s vision through surgery, it’s a very special moment. As an inventor and surgeon, I’m happy to look back on my contributions to the field, as I feel I have played a part in the continuing advancement of the specialty I love. Finally, I have always worked to increase the availability of eye care for those who can’t afford or access treatment, using community outreach programs and telemedicine. I have also been involved in efforts to educate visually impaired people on the technologies and programs available to assist them – such as working with an organization that provides computers configured with assistive technology to blind children in Kenya and Tanzania. I’ve always worked to further my belief that sight is a basic right, and the ability to access treatment shouldn’t depend on where, or who, you are.References

- The American Academy of Ophthalmology Museum of Vision Oral History Collection, “Bath, Patricia, MD”, (2011). Available at: http://bit.ly/1DS1mRE. Accessed May 18, 2016. P Bath et al., “Excimer laser lens ablation”, Arch Ophthalmol, 105, 1164–1165 (1987). PMID: 3632429.