Smartphones hold much promise for ophthalmology outside of the clinic. Their cameras are continually improving in terms of sensor resolution, light sensitivity, and lens quality. The LED flashes provides a steady, illuminative light source, and the hefty processing power and high-resolution displays and high-speed network connections onboard mean that images can be acquired, analyzed, annotated, stored and shared in minutes on the same device. All that’s needed is the right app (FiLMiC Pro, as it allows on-the-fly focus and exposure adjustment) and a €20, 20 D lens held at the right distance (which can be tricky to master), and (discounting the cost of the smartphone), you have an inexpensive ophthalmoscope (1) – and with it, inexpensive telemedicine. It just looks ugly!

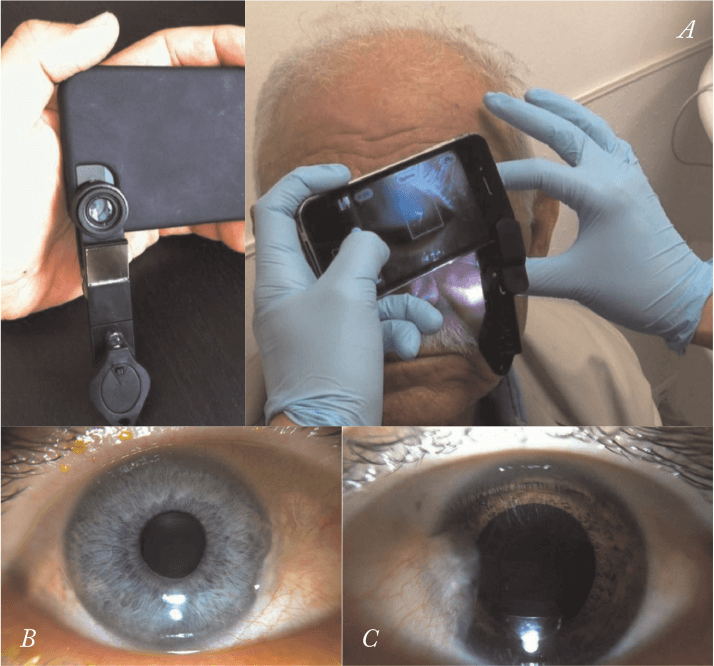

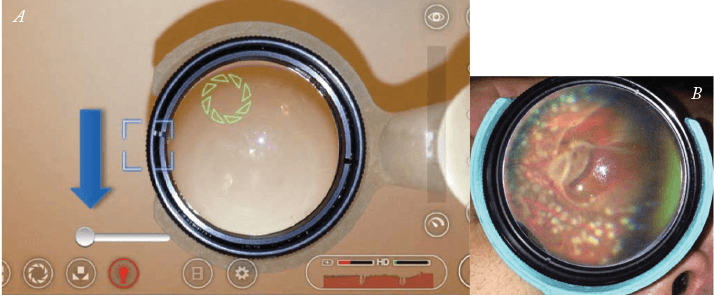

Industry can help here; for example, Welch Allyn will let you pair its €540 PanOptic Ophthalmoscope with a professional-looking €65 iPhone adaptor. That’s fairly frugal but only if you already have the ophthalmoscope – but certainly isn’t if you don’t. But now there’s a middle way. Robert Chan and David Myung of Stanford University have designed two cheap, smartphone accessories, and published them in the March issue of the Journal of Mobile Technology in Medicine. The first device can clip on to any smartphone and consists of a macro lens with a 2.5 cm focal length, attached onto a clip, and a “properly positioned” LED light source that illuminates the eye – and can be used as a substitute for a slit lamp (2). It is easy to use: switch on, hold with both hands; gently touch the patient’s head with a couple of fingers so that you can rest the phone on those fingers (enabling you to hold the lens at the correct distance to image the eye) and operate the touchscreen buttons with a spare finger on the other hand. The team’s second device, developed in conjunction with Mark Blumenkranz, is a 3D-printed iPhone attachment that contains a mount for an indirect ophthalmoscopy condensing lens. The mount is positioned at a prescribed (but adjustable) distance from the iPhone’s camera lens, enabling focusing of the image onto the retina for fundus imaging. As before, FiLMiC Pro is being used as the image acquisition app.

These devices were designed to be inexpensive, with production costs being approximately €65 at the moment. “It took some time to figure out how to mount the lens and lighting elements to the phone in an efficient yet effective way,” said Myung, who built the prototypes with inexpensive parts purchased almost exclusively online, including plastic caps, plastic spacers, LEDs, switches, universal mounts, macro lenses and even a handful of Lego blocks. The simplicity of the second device, however, allows it to be 3D-printed, which means that anyone with a 3D printer and enough plastic substrate can build their own. Such printers are popping up all over the world, from battlefield hospitals to aid agency centers in rural areas of developing countries. As the substrate is cheap powdered plastic, once the printer is in place, producing such instruments could be as simple as downloading the designs and pressing print. Perhaps we’ll all be printing inexpensive iPhone indirect ophthalmoscope adapters sometime soon.

References

- L.J. Haddock, D.Y. Kim, S. Mukai, “Simple, Inexpensive Technique for High-Quality Smartphone Fundus Photography in Human and Animal Eyes”, J. Ophthalmol, Article ID 518479 (2013). doi: 10.1155/2013/518479. D. Myung et al., “Simple, Low-Cost Smartphone Adapter for Rapid, High Quality Ocular Anterior Segment Imaging: A Photo Diary”, Journal MTM, 3, 2–8 (2014). doi:10.7309/jmtm.3.1.4. D. Myung et al., “3D Printed Smartphone Indirect Lens Adapter for Rapid, High Quality Retinal Imaging”, Journal MTM, 3, 9–15 (2014). doi:10.7309/jmtm.3.1.3.