For its variety and satisfaction, I’d like to stake a claim for having the best job in the world. There is simply no such thing as a ‘typical’ day for me. Today, for example, kicked off with a major policy discussion with the senior management team of the LV Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI). Later, I spent time with our scientists, listening to some exciting recent research on genomics before turning attention to this article. Tomorrow, I may be immersed in mobilizing our resources, building bridges with other organizations, or forming national and international collaborations. I am 68 years old, I still love it and have no intention of retiring in the traditional sense in the foreseeable future.

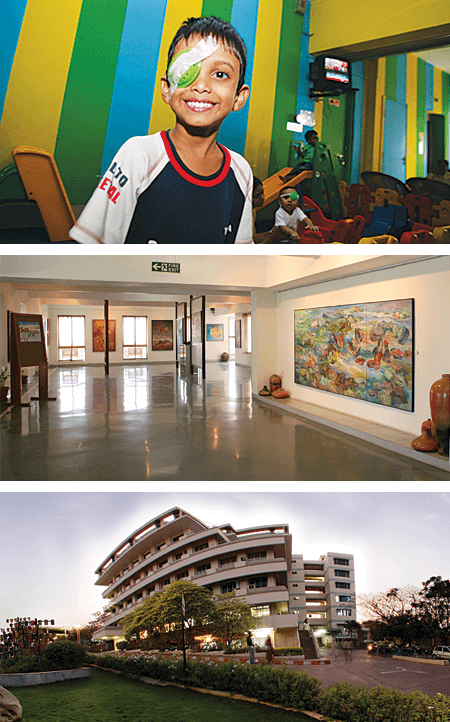

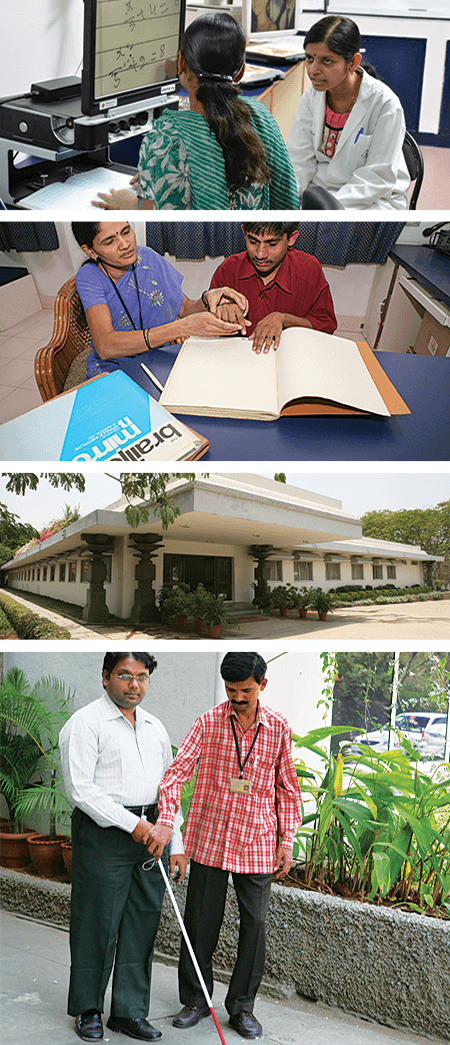

LVPEI is a comprehensive eye health facility. At the main campus, located in Hyderabad, India, we offer full patient care, sight enhancement and rehabilitation services, as well as pursuing cutting-edge research and providing training for all levels of ophthalmic personnel. We also run high-impact rural eye health programs, including 100 primary, 11 secondary and three tertiary centers at various locations; these are mainly in the state of Andhra Pradesh, with a lesser presence in the neighboring states of Odisha and Karnataka. Our mission is to provide equitable and efficient eye care to everyone, across all sections of society. Since the hospital was established in 1987 we have provided care to over 17 million patients, more than half of whom have had services completely free of cost, regardless of the complexity of the procedure (see Table 1 for more indicators of the impact of LVPEI).

In this article, I shall lay out the philosophy of LVPEI, the origins and development of the hospital system and the potential applicability of the model to other cities and countries of the world. To do this accurately, I shall also provide a little information on my background and career – I’ve had wonderful mentors and chance encounters with munificent benefactors, and their part in the story deserves to be recognized. My constant concern is the lack of uniform standards in medical care and education in India. There are pockets of excellence, including ours, but we need uniform excellence across the country, and that is lacking and it will get us into a lot of trouble, if not corrected.

Origins

Nineteen seventy-four was a significant year in my life: my wife and I moved to the United States of America for my fellowship training. I initially joined Jules Baum at Tufts University in Boston, then Jim Aquavella in the University of Rochester, New York. It was the start of a dozen wonderful years that influenced our entire lives. For my part, I not only matured as a professional – the medical opportunities I had could not have been matched anywhere else – but also as a person. Jules and Jim turned me into a solid cornea specialist, teaching me the best practices for management of corneal problems; crucially, they also taught me the right approach to excellence in patient care. That period set the entire course for the rest of our lives, inspiring us to return to India to do the work that has, for the over quarter of a century, defined my career. Throughout, I have relied on the immense support, partnership and guidance of my wife, Pratibha.As a young medic I fancied pursuing cancer research, but my destiny was to be an ophthalmologist, like my father. He had gently nudged me towards his specialty, but looking back at my medical school years, I found it the most interesting anyway. Before the US experience, a huge influence on my residency training in Delhi was Professor Agarwal; he instilled in me the right way to think about and approach ophthalmology. Pratibha and I had always intended to return to India but we started thinking seriously about it in 1982. We decided to fix a date and to hand in our notice, otherwise we might never have ended up returning. I gave my employers four years’ notice in 1982, telling them that we’d be leaving in the second half of 1986. Because of the long notice period, nobody took it seriously, but we were true to our word, and by October 1986, we were back in India.

The vision was limited when I look back and compare to what has been done, but at the time it seemed to be outrageously ambitious. I wanted to develop an academic eye center based on those I was working at in the USA. It would have tertiary care, education and research components; the only thing I added to that list that Western centers didn’t have was a rehabilitation center for the irreversibly blind as an integral part of the Institute (which has been a central pillar of our activities ever since). The aim was to be truly comprehensive rather than a center that operated on a single disease, like cataract, as was the tradition at the time in India.

What we gradually realized was that there was an incredible amount of avoidable (preventable and treatable) blindness occurring in India, particularly in rural areas. LVPEI performed an epidemiological study in the mid-nineties, and we discovered that over three-quarters of blindness in our home state of Andhra Pradesh was avoidable: the diseases – cataract, correctable refractive errors and infection – were treatable but people just weren’t receiving treatment. It was clear that our mission had to be expanded. Over the years we have opened primary, secondary, and tertiary centers, bringing eyecare to some of the remotest villages in the region. We now operate in 120 locations, 100 of which are in remote rural villages. This makes me proud. I grew up in a small village, and the system we have created today reaches people who live in such villages. They have the best eye care that we can provide. The planning and development of the institute was informed by how other prestigious eye institutes operated. I visited many centers of excellence, in India and around the world, making copious amounts of notes. But what I wanted to replicate boiled down to two key aspects: equity – we insist that all patients are treated equally – and excellence through smooth, efficient systems.

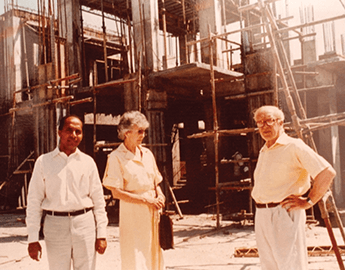

The reaction of the ophthalmology community in India at the time was mixed. Some of those in the medical establishment embraced the idea and were very encouraging and supportive; others, whether driven by skepticism or jealousy, did what they could to kill it. But overall, there weren’t that many obstacles that needed to be overcome. Plans for the institute were progressing well, when something serendipitous happened. A mutual friend in America, Ratnam Mullapudi, introduced me to Ramesh Prasad, son of the veteran Indian film producer, LV Prasad. The Prasads immediately believed in the project and their involvement dramatically accelerated its development. They provided land that was in a better location than what we had at that time, and donated approximately US$1 million in funds that enabled us to build a 50,000 square feet hospital. The name of the institute recognizes Prasad’s noble act.

Running the Institute

Within five years the institute had earned a substantial reputation in India and had made some kind of impact on the global scene. The former made it far easier to mobilize resources within India – before that we were depending mostly on funding external to India. We have had a significant influx of funding and support from within India in the last seven or eight years, which has been a very welcome development. That’s partly due to the astonishing economic progress that the country has experienced in recent times. Of course, that is not without its problems: there has been tremendous social upheaval and a sickening level of corruption that erodes the country’s integrity. We don’t pay any bribes to anybody at any level, meaning that certain things, such as obtaining essential permits, has become very slow.Having said this, funding is an issue that is always with us. Concerted effort and sound management mean that LVPEI has no bank loans or budget deficits, yet more than half of all of our patients are treated free of charge, and an even greater proportion in our secondary and primary centers. To achieve this, we are very, very cost conscious about everything except the needs of the patients – on that we never compromise. We restrict all other expenses, and spend only what we earn. I am no financial wizard. We use simple, transparent systems that I can understand and feel comfortable with. That’s not to say that we’re not excited by technological innovation: we are. However, we set a high bar for the cost effectiveness that new developments provide and thoroughly evaluate new instruments and equipment before introducing them in our centers. To provide a recent example, LVPEI decided against laser cataract surgery. Our experts believe that it offers no specific advantage over the current system of phacoemulsification and other methods of cataract surgery. Nevertheless, we continue to implement state-of-the–art procedures where appropriate, and we use most current technologies.

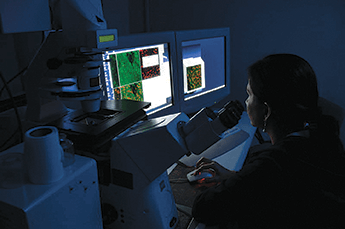

We are also contributors to innovation in ophthalmology. The latest development, begun in October 2013, is a collaboration between LVPEI and the Camera Culture group at the Media Lab of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Called the Srujana Centre for Innovation, the goal is to develop state-of-art technology to diagnose and provide efficient treatment for all kinds of blindness, including breakthroughs for those living in remote areas. I find this work truly exciting. We initiated the project with a one-week workshop attended by a hundred engineering students from across the country. It resulted in twenty-seven prototypes and work has commenced on translating all that potential into something tangible. Already, a way of performing refractive tests on mobile phones has been developed (http://web.media.mit.edu/~pamplona/NETRA/), and other applications are in the works, from a portable ERG machine to a new system for detecting ocular disease in newborns.

One reason that LVPEI has developed into a successful center is that we have recruited the right people. This starts with getting the “right kind of people” – people with standards, people with values. We have never compromised on that. Indeed, many positions have been left unfilled, sometimes for years, until the right person is found. What are we looking for? The right background, including education and anything we can discern about the kind of work that they’ve performed previously. Integrity is absolutely essential. As noted earlier, corruption is abhorrent to me. In addition, our staff must fully share the commitment to provide the best of care to all patients, regardless of their circumstances. In the past, I did not hesitate to suspend privileges of a surgeon who was overheard telling a patient not to be difficult because he was “non-paying.”

I used to ask senior doctors directly in the interview, “Are you one of the top five in your area in the country today?”, and to junior doctors I’d ask, “Do you promise me that you will become one in the next five years?” That’s the stand that we took. So really, my ethos can be encapsulated by the three E’s: Equity, Efficiency, and Excellence. Once we have the right staff in place, my role is to provide them with the tools that they need to be successful. Actually, I adjust my management approach to suit the situation. So, some people have called me a dictator while others insist that I delegate too much. What I actually do is this: I hand over a particular area of responsibility to what I believe is the right person. If they run with it, and run with it well, then I don’t intervene again. But if it’s not going so well, I involve myself quite a bit, gently or not so gently, to get things right.

LVPEI to the world

Today, LVPEI offers the whole gamut of ophthalmological services, from the provision of contact lenses to medical retinal services, and everything in between. We have thriving educational and research centers, and with the Ramayamma International Eye Bank, we have the single largest provider of corneal tissue for grafting in India.

Our methods of running both the LVPEI and our outreach centers are being studied and imitated in many developing countries. Could Western countries also benefit? Well, the United States has a large population of poor people whose health needs are chronically underserved. I have had informal conversations with people from the US about the LVPEI model, but I don’t think that anybody is seriously implementing our approach at the moment. The American system has all the ingredients in place, it would just be a matter of changing the menu to offer different products. I believe that with 10 to 15 percent of their budget they could provide full care for poor inner-city and rural populations. Perhaps that’s something for the future. For me, it would be wonderful to give something back to the country that offered me so much.

In the meantime, there are so many exciting things going on. The days of indulging in favorite pastimes – golf, reading and sleeping – are far off. But when I do eventually leave, I want LVPEI to be in a situation like it is today: growing, innovating, financially sustainable, a world-renowned center – and treating all, equally. And I hope the next person sitting in my chair will do better than me.

Table 1. LVPEI by Numbers

- Direct service is provided to about 2,000 villages through secondary and primary care

- Around 16,000 eye care professionals from India and abroad have been trained

- 29 PhDs have been awarded and over 1,300 research papers published

- Assistance has been provided to rehabilitate over 120,000 persons with irreversible blindness or low vision

- More than 47,000 donor corneas have been harvested, nearly 25,000 of which have been transplanted to needy patients

- Permanent infrastructure has been established in 18 of the 23 districts of Andhra Pradesh

- Eye care programs have been upgraded in 18 states of India and 16 other countries

What others say

Brien Holden, Professor at the University of New South Wales School of Optometry and Vision Science, and CEO of the Brien Holden Vision Institutes in Sydney, Australia, and Guangzhou, China.“When Nag went back to India to establish the LV Prasad Eye Institute we began working together and I made the first of my now 54 trips to India. He was determined to build a center of excellence that would research the best possible ways to advance the welfare of his people through delivery of vision care and blindness prevention.”

“Three decades later, tens of millions in India and hundreds of millions around the world have been helped by his eye care delivery systems, the knowledge LVPEI has generated and the training of thousands of eye care professionals. On a global level, Nag has led a renaissance in evidence-based eye care and through his work with the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness, WHO and the numerous partner NGOs and Institutes created a revolution in blindness prevention.”

Sreekanth Ravi, CEO and President of Tely Labs Incorporated, philanthropist and serial information technology entrepreneur.

“My brother Sudhakar and I have worked with Nag Rao and the LVPEI for over ten years. We have been, and continue to be, very impressed with the work and the dedication of the team, especially the good doctor himself. Whether it involves cutting-edge stem cell research, or day-to-day eye exams and related procedures, the LVPEI has become an integral part of the community and is recognized as a global leader in research and new procedures. All of this emanates from the commitment and dedication of Nag and his team; we are very proud to be associated with them.”

Ashok Devineni, Chairman of Nava Bharat Ventures Limited, a multinational power, mineral and agribusiness conglomerate.

“Our involvement with the LVPEI began 25 years ago, and our support, initially modest, has grown substantially since then. We have derived enormous satisfaction from the support we have given to some of their projects, as they have delivered far in excess of what we expected, in terms of quality, equity and efficiency of their eye

care services.”

“The projects that we helped fund – an eye bank, a tertiary eye hospital and a secondary eye care center in a rural area – have become so large and successful that our donations pale in significance. One change ushered in by the LVPEI was equality in patient care: every patient is treated with the same level of high quality care without exception, which contrasts with the ‘VIP’ culture that was commonly prevalent in India at the time of the hospital’s inception.”

The Vision 2020 Initiative

I was heavily involved with the “VISION 2020: The Right to Sight” initiative when I was President and CEO of the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), between 2004 and 2008. Our target was a world in which no-one is needlessly blind, a world where those with unavoidable vision loss can achieve their full potential; our goal was to achieve this by the year 2020. The program has had many successes, all driven by cross-sector collaboration, which enables public, private and non-profit interests to work together. All avoidable causes of blindness will not be eliminated by 2020, so the challenge still remains. Having said that, we implemented a framework that has started deliver quality care to people across the world. It’s up to each country to move forward in implementing blindness prevention programs using that framework; in this way, the world can at last eliminate needless blindness and suffering.