- Many patients present with epiphora; excessive tearing – which is unpleasant for the patient and can cause issues with vision

- The condition has many underlying pathologies, but can be broadly grouped into two main causes: overproduction or under-drainage of tears

- Overproduction of tears can result from conditions such as dry eye disease or eyelid abnormalities, whereas under-drainage can result from obstructions in the lacrimal system

- We provide guidance on the different causes of epiphora, advise on diagnostic techniques and summarize the treatment options.

Epiphora, or excessive tearing, is a common complaint seen in any eye practice. Excess tears can be bothersome, embarrassing, and even impair vision. Tearing patients are often assumed to have one of two broad problems: dry eye or a nasolacrimal obstruction. Artificial tears are often prescribed for presumed dry eye disease, but these can make matters worse if a lacrimal drainage obstruction is present. On the other hand, many physicians recommend tear drain surgery if their patients’ excess tears are attributed to increased tear secretion. Epiphora can be caused by a wide variety of problems and difficult to diagnose, so a systematic approach is necessary for teary-eyed patients.

Tear physiology

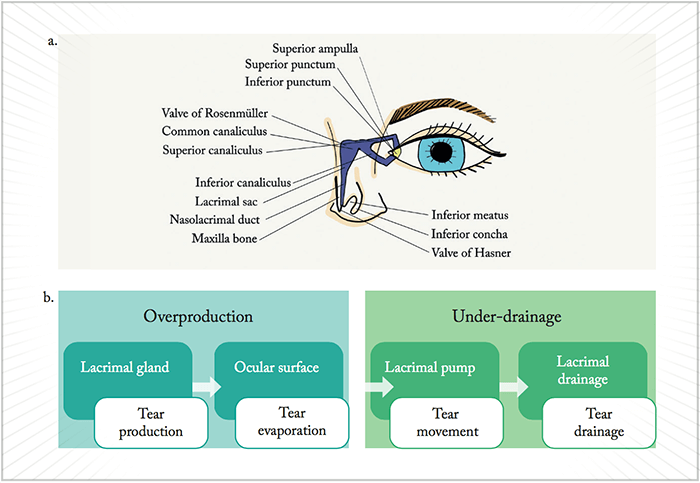

The lacrimal and accessory lacrimal glands produce tears at a basal rate of around 1.2 μL/minute, but reflex tearing can increase this rate by 100-fold. Each blink spreads the tear film evenly over the ocular surface, and evaporation eliminates 10–20 percent of the tears volume. Contraction of the orbicularis muscle pumps most of the tears into the upper and lower puncta where they eventually enter the nose through the nasolacrimal duct (Figure 1a). A tear capacity of 8 μL rests on a delicate balance between production, evaporation, and drainage. Any disruption of this balance leads to tear overflow. Hence, it is helpful to think of epiphora in terms of overproduction or under-drainage (Figure 1b).Overproduction

Ocular surface disease Dry eye disease is ubiquitous and perhaps the most common cause of tear overproduction. Surface dryness or irritation stimulates reflex tearing that can exceed lacrimal drainage. Blepharitis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca, trichiasis, lagophthalmos and exposure keratopathy, allergic conjunctivitis, and medicamentosa can all also lead to over-secretion of tears. Identifying the correct underlying etiology is necessary to properly treat the surface. What to look for:- Increased tear lake height

- Decreased tear breakup time (TBUT) <10 seconds

- Devitalized corneal epithelium using topical rose bengal or lissamine green

- Epithelial defects or erosions on fluorescein staining

- Misdirected eyelashes

- Poor eyelid closure.

- Eyelid malpositioning (for example, entropion, ectropion, floppy eyelids, trichiasis, retraction [Figure 2], lagophthalmos)

- Facial asymmetry

- Weak eyelid closure, abnormal blink reflex, or decreased blink rate

- Eyelid laxity.

Under drainage

Obstructive lacrimal drainage disorders A soft rule of thumb is that if excess tears flow down the cheek, as opposed to just making the eye “watery,” a tear outflow problem may be present. Problems in the “plumbing” can occur anywhere from the punctum, canaliculus, nasolacrimal duct, to the nose. Punctal eversion, or ectropion, is usually easily identified. Punctal plugs commonly used to improve dry eye can migrate within the canaliculi, becoming a source of obstruction. Less frequently seen, punctal and canalicular stenosis can result from inflammation (for example, Stevens-Johnsons syndrome, ocular pemphigoid), infection (for example, herpes), chronic bacterial inflammation (for example, caused by Actinomyces israelii), medication (for example, pilocarpine, epinephrine), or trauma. A general rule for assessing stenosis is that the normal lumen should be the same size (or bigger) than the end of a paperclip. (But do not actually poke the eyelid with a paperclip!) The most common cause of tear outflow obstruction is acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLDO) or stenosis. Other possible causes are dacryoliths, dacryocystitis, chronic sinus disease or prior sinus surgery, trauma, and rarely, sino-nasal or lacrimal sac malignancy. What to look for:- Lacrimal obstruction (see “lacrimal drainage system irrigation” below)

- Fullness over the lacrimal sac on palpation, indicating dacryocystititis

- Nodular fullness over lacrimal sac, which could indicate neoplasm

- History of eyelid trauma

- History of sinus disease

- History of punctal plug use

- History of bloody tears, suggestive of malignancy.

Probing for a diagnosis

A thorough inspection of the eyelids and ocular surface is the first step in determining the cause of epiphora. Three essential diagnostic tests can further guide your diagnosis:- Dye disappearance test (± Jones I and II test)

A drop of fluorescein is instilled into the conjunctival fornix of each eye. Instruct the patient to not wipe or touch their eye. After five minutes, the dye should clear spontaneously if there is no obstruction. Persistent or asymmetric clearance suggests possible obstruction, especially if dye is seen flowing down the eyelids and cheeks. The Jones I and II tests attempt to recover fluorescein in the nose. Since nasal swabbing can be uncomfortable and misleading, many skip Jones testing and proceed with lacrimal syringing. - Snap and distraction test

This exam technique assesses eyelid laxity. The lid is pulled down or away from the globe. Stretching the lid >8 mm indicates excessive laxity. After releasing the lid, it should take <8 seconds for the lid to “snap back” to its normal position. Poor appositional return also suggests laxity (Figure 3). - Lacrimal drainage system irrigation

After applying topical anesthesia, a blunt lacrimal cannula on a syringe with normal saline or water is inserted into the punctum with some lateral traction on the lower eyelid. The cannula is gently advanced. When no obstruction is present, the cannula moves easily. Next the syringe is depressed. If tear drainage is normal, saline or water should pass freely into the nose or throat without reflux. The patient may cough, swallow, or otherwise grimace with the sensation of fluid in their nasopharyngeal area. Difficulty advancing or fluid reflux indicates some level of obstruction. When the fluid refluxes from the same punctum (or one cannot irrigate at all), a canalicular obstruction is likely. Reflux occurring through the opposite punctum points to a blockage at or distal to the common canaliculus. Pus or mucous reflux points to a dacryocystitis.

Treatment

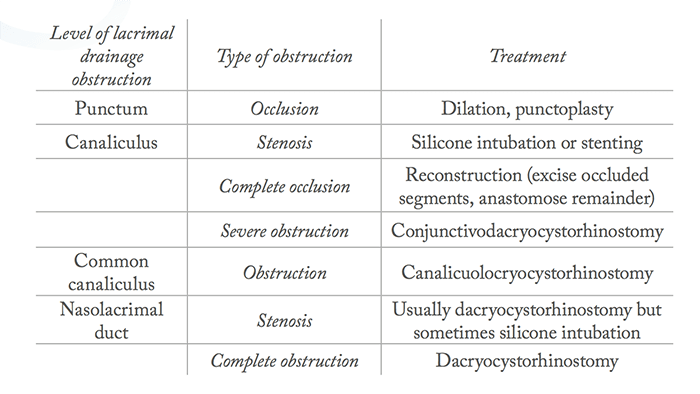

Once again, correcting the underlying cause is key to treatment. A large percentage of patients will have ocular surface disease requiring only medical management. Trichiasis can be temporarily managed with epilation or ablation, but more severe eyelash misdirection may need excision, eyelid reconstruction, or mucous membrane grafting. Patients with either an outflow or a plumbing problem will more likely need surgical correction, for which the specific treatment is based on the level of obstruction (Table 1).

Eyelid laxity and involutional ectropion are often corrected with eyelid tightening procedures, such as a lateral tarsal strip or lateral canthopexy. Punctal or canalicular stenosis may respond to silicone intubation or stenting. For a NLDO, a dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) is the treatment of choice. The goal of this procedure is to bypass the NLDO. This is accomplished by creating an anastomosis from the lacrimal sac through the adjacent bone to the nasal cavity. If the blockage is at the common canaliculus, a DCR may work, but a conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CDCR) with a Jones tube that bypasses the entire native tear outflow system may be indicated. DCR is one of the most common tear outflow procedures. A stent is usually placed temporarily across the new tear passageway during the healing process. Some common complications include persistent tearing, infection, bleeding, early loss of the stent leading to occlusion, and sinusitis. However, prognosis is excellent, with success rates of greater than 90–95 percent (1).

In summary

Causes of epiphora can be multi-factorial, and unless there is an obvious complete drainage obstruction, treatment should begin with noninvasive options. Helping your patients understand the basic physiology of tears and partnering with them to find the best treatment is the first step to ending those waterworks. Elizabeth Shen is an ophthalmology resident at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, University of California, Irvine, USA. Jeremiah Tao is chief of the oculofacial plastic and orbital surgery, program director and associate clinical professor at the Gavin Herbert Eye Institute at the University of California, Irvine, USAReferences

- American Society of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. “Tear System”. Available at: http://bit.ly/ASOPRS. Accessed September 21, 2017.