- IMTs can improve vision in patients who are beyond the aid of anti-VEGF and photodynamic therapy

- Patients must have at least one phakic eye to receive an IMT

- Collaboration between ophthalmologists, low vision specialists and post-surgical care teams is essential

- Rehabilitation is central to successful outcome

Meeting a patient who has vision loss due to bilateral geographic atrophy for the first time, particularly one who has to use prescription handheld magnifiers, can be a sad occasion. The patient is struggling to carry out the everyday tasks that help him or her to lead an independent life and, dispiritingly, we ophthalmologists have had very little to offer them. Several high technology implantable devices have been developed over the years, but I didn’t have enough confidence in any of them to recommend them to my patients. Now, one device has changed my mind – an implantable miniature telescope (IMT).

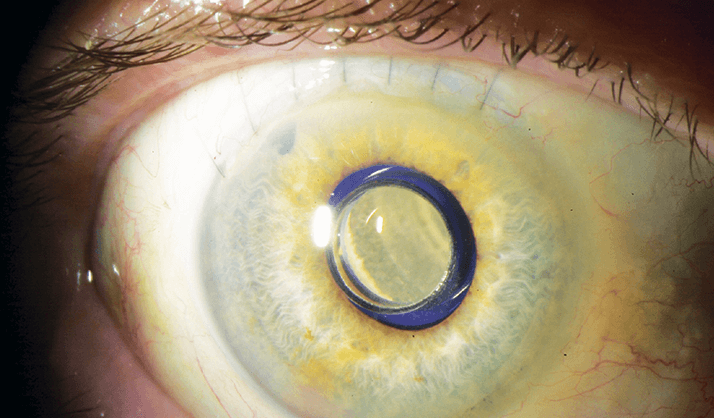

I first encountered IMTs in 2008 through a Belfast-based colleague, Giuliana Silvestri, who led a UK clinical trial (1) of the first ever implant approved for end-stage macular degeneration (AMD). The CentraSight Treatment Program developed by VisionCare Ophthalmic Technologies utilizes a tiny telescope implant developed by Isaac Lipshitz. It significantly improves functional visual acuity and quality of life in a pre-selected subgroup of patients who have lost their vision due to AMD. Patients with end-stage or late disease who qualify for this treatment are either profoundly visually impaired or blind (visual acuity 6/24 to 6/240) and must meet other criteria. The telescope implant is Conformité Européenne (CE)-marked and the treatment has Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval and Medicare funding in the United States.

The IMT replaces the eye’s lens and projects (three-fold) magnified images onto undamaged peri-macular regions of the retina. Patients must have at least one phakic eye; the implantation process involves removal of the patient’s own lens, with the device being secured into the capsular bag. As with any telescope, images are larger but the field of view is reduced. The IMT has a field of view of approximately 20°. Nevertheless, the implanted eye processes detailed vision, with the non-surgical eye taking responsibility for peripheral vision tasks, including ambulation.

Patient selection

Not all patients are suitable for an IMT; they must match exacting inclusion criteria and undergo a rigorous assessment process using an external telescope simulator and patching of the stronger eye. This is a process of discovery for the patient and the surgeon that takes about a week to complete. Strong IMT candidates include those with:- Bilateral non-foveal-sparing geographic atrophy

- Neovascular AMD where conventional treatment with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) drugs or photodynamic therapy has failed

- Stable neovascular AMD

Patients who have had active choroidal neovascularization within the last six months are unsuitable for the procedure. Optometrists and ophthalmologists have to work together closely for this procedure to be maximally successful. The optometrist helps determine which eye is best-suited to receive the implant, typically with an eye-selection algorithm. An important part of the process is patient education. Low vision specialists and occupational therapists set patient expectations on what functions can be regained as well as informing the patient about post-implantable rehabilitation – this also helps to determine the patient’s willingness and ability to undergo the procedure. Patients who have undergone the procedure will be able to read and have better distance vision, but driving will forever remain out of the question.

Surgery and rehabilitation

For younger surgeons who are more used to phakoemulsification, this may be the largest incision cataract surgery they’ve ever performed. For me, it was a relatively new departure to be working with a 12 mm incision. The device is roughly the same thickness as five intraocular lenses, and is implanted in what amounts to a hybrid of cornea and cataract procedures. The rehabilitation process is absolutely critical – three to six months’ of rehabilitation work after surgery is necessary, and getting a visual rehabilitation team in place is the most important piece of the puzzle. Rehabilitation aims to bring everyday items into view for the patient, such as large-print books; it helps him or her to identify commonly used items around the house and to gain the ability to focus on the images – and hold their view there. If the patient were to be left to his or her own devices after surgery, I don’t think they’d use the device. The magnification is powerful, and, to give an example, some of the patients I met who had been in early trials told me that they’d taken fright at the size of the television. Often these patients buy big, high resolution TVs and when the telescope then magnifies the image threefold, it’s a shock. Rehabilitation involves training the patients to get used to the larger images, and to use them. They need to practice daily to be able to bring the magnified image in and use their other, non-implanted eye for peripheral vision.End-stage AMD is a growing public health issue as the population ages. Ocular implant technology has matured enough to provide a genuine alternative to prescription magnifying glasses for patients with end-stage AMD. IMTs improve the vision of these patients and with it their independence, quality of life and dignity.

David Keegan is a medical retinal specialist surgeon at Mater Private and Mater Misericordiae Hospitals, both in Dublin, Ireland.