- MAG Optics, our early-stage ophthalmic device company, are in the process of bringing two such devices to the market

- One is a fresh take on an accommodative IOL design, that features dual optics, and the other is a novel approach to corneal implants

- We’ve learned that to get by, you need to be nimble, ready to receive feedback from the experts, and work with the right people

- Each setback has helped us improve and we now have our end goal – our products in the clinic – fully in view.

On the battlefield, necessity is the mother of invention – and my father, Marwan Ghabra, can attest to this. Between 1998 and 2012, he was based in Syria, setting up two specialist eye hospitals. During this time, the second Iraq war broke out – and at one point, 60 percent of the workload in both eye hospitals were casualties of war, and conflict-related injuries are some of the most challenging cases there can be. The practice of ophthalmology under these circumstances is a rapid incubator of two skills: on-the-spot improvisation and the ability to innovate your way out of a situation. He tells many stories that stretch belief of how he’s “MacGyvered” his way out of some incredible surgical situations – were it not for his surgical video library, nobody would believe him.

Today, my father practices ophthalmology in the UK as a consultant ophthalmic surgeon at London’s Whipps Cross University Hospital – but even amongst the terraced houses of the North London suburb of Leyton, he still requires the same skills that served him so well in the arena of war, and the last 30 years of clinical practice of ophthalmology. I am also a surgeon and, I suppose, as CEO of MAG optics (which my father and I founded), this makes me a “doctorpreneur” too. For the last few years, my father and I have been developing and refining designs for two novel ophthalmic devices – one, a presbyopic accommodating IOL, the other, a novel corneal inlay design for the treatment of a wide array of refractive errors. Both are almost at the proof-of-concept phase. So how did we get there?

Discussions over dinner

If you gather a group of surgeons together at a dinner party, inevitably, the discussion will turn to work – the triumphs, disasters, hopes and frustrations are all voiced as the evening progresses, with anecdote after anecdote piling as high as the plates that need washing up later. When my father and I sat down for dinner, we would tackle the meatier “What if?” questions: What if we could produce a truly accommodative IOL? How might you correct the cornea with something that incorporates design elements that account for differences in individual curvature and thickness? Given the highly complex nature of the eye’s anatomy, what could we do that is unique? Once the ideas were formed, the next question was always, “What would it take to..?” Dad was always bristling with new ideas and designs, because quite frankly, at heart, he is an inventor – and someone who is rarely content with available technology. These discussions over dinner inevitably led to doodles on napkins. In our family, the next step after that is to mock up prototypes using whatever’s to hand – like spare contact lenses and superglue. It might sound cliché, but that’s really how we got started. If we think we have something that shows promise, the next question is: why not? The “Why Not?” is the meatiest question of all – ideas and prototypes built on the kitchen table can easily be dismissed as food for thought, but there comes a point where, if you believe in your concept, you have to take the next step. It was this, borne of our insatiable curiosity and an overarching desire to improve the lives of patients that has led us on a rollercoaster journey from the ideas for both devices, to their initial designs, and far beyond. Now we find ourselves not asking “Why not?” but we are building a company to develop what we believe are game-changing technologies for the treatment of cataracts, presbyopia, and broad refractive errors.

When the day job informs the development

My father’s ‘day job’ sees him give out substantial amounts of advice – not just on the planning of complex surgical procedures, but also in the training of junior doctors. It’s his 30 years of experience in bridging the gap between theory and practice that gives him the authority to do that – and it’s this experience that’s been invaluable in the development of our IOL and corneal inlays. If we focus on the development of the IOL for the moment, it’s quite a challenge to come up with a solution for the cataract surgery-induced loss of one of the most complex natural biological processes: lens accommodation. At this point, we should acknowledge the excellent work of Daniel Goldberg, whose computer animated models of accommodation and the theory of reciprocal zonular action has been invaluable, as it supports the unique mechanical aspects of our two part, dual optic, accommodating IOL. He’s enthusiastic about our design, noting that it “holds the promise of achieving a lasting solution to correcting both near and far vision with an intraocular lens.” It’s this combination of experience and maintaining a scholarly interest in the latest developments that’s given us the confidence to take our ideas and run with them.Keeping an eye on the anatomy

What we’ve learned on this journey is that the lens needs to be designed to address the inevitable failure of the anatomy, and this lens needs to be unhindered by capsular fibrosis. The second lesson was that as every patient’s needs and eyes are different, the lens needs to be customizable – so our IOL design has an adjustable component of the lens that can be modified by the internal diameters of the eye. Finally, the lens must be designed in a way to prevent posterior capsule opacification and we’ve done that by developing a new approach that utilizes aqueous flow. The IOL currently requires a degree of intraoperative positioning, which does mean that a small amount of initial surgeon training will be required, and the positioning may prolong the procedure by a few minutes – but this is not unlike any other new technology. One of the challenges we found was ensuring that the rest of the surgery aligns with industry standards – like keeping incision sizes down to 2.8 mm. Helpfully, we managed to achieve that relatively early in the development process, and we have managed to have these designs vetted by external engineering teams and some of the biggest-name IOL experts in ophthalmology – and have received some very positive and encouraging feedback.Cadaver eyes and corneal topographers

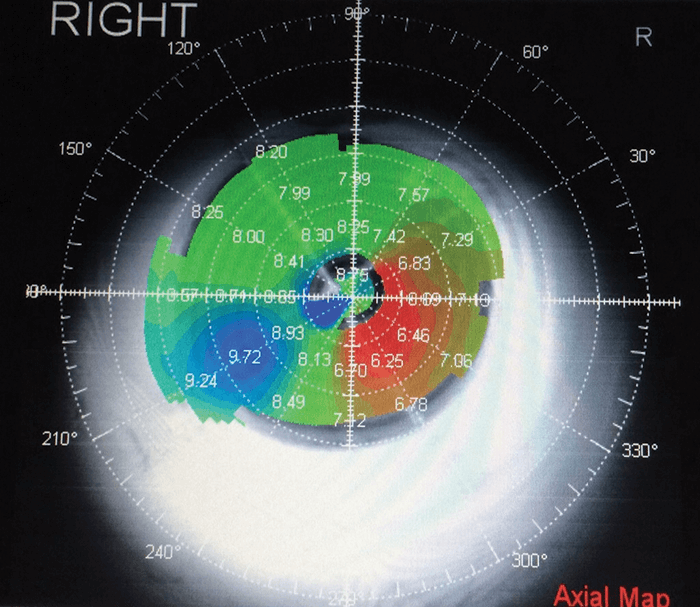

Moving onto the work that we have done to develop the corneal implants for use in patients with refractive error, presbyopia or keratoconus, we’ve gone through the same journey – from several design iterations to cadaver implant work. We had two objectives. First, we wanted to preserve the sanctity of the central optical zone. Second, it should be customized to adapt to patient’s corneal thickness and curvature allowing for superior patient outcomes. We’ve managed to achieve good results early on using the implants to treat astigmatism in cadaver eyes. One example was a cadaver eye with 2.25 D of regular astigmatism. When the implants were implanted on the steep meridian, the degree of astigmatism was increased by 3 D. However, topography revealed that there was a coupling effect on the cornea, in a 1:1 manner (Figure 1). Within the coupling effect, we noticed that when the two implants were placed at 90° to the steep meridian, this results in a reduction of 3 D in the steep meridian, and the overall result of placing these implants in the cornea was a reduction of 3 D in the steep meridian to 0.5 D of astigmatism.Partnering with the appropriate professionals

Organizing and securing finance has also been a challenge. This is where the third co-founder of MAG Optics comes in – Chicago-based Geeta Singh. Geeta has over 25 years of business management and boardroom expertise, the kind of non-technical – but absolutely essential – business management and strategy planning skills that we needed. She has truly been the driving force behind the transformation of an idea into a viable business proposition. She’s also the person that has dealt with that two-ton elephant in the room: capital. So far, MAG optics is bootstrapped, milestone-driven, and extremely cash-conscious, but we’re seeking seed capital to advance the development of the prototypes, to test them, and to implant them. In addition to Geeta, there were two important skills that we needed to turn to other professionals for. First: engineering. We’re working with the University of Liverpool’s Professor of Biomaterial Mechanics, Ahmed Elsheikh, to perform finite element analyses (FEA) that will allow us to place the implants in the most optimal position, and we’re now on our third prototype. FEA has also let us identify and pre-test design elements for the IOL, helping us streamline the iterative design process for the lens. As of today, we have a working prototype, and we’re expecting to have initial results within the next few months. The use of FEA, simulation data and analytics has been crucial in refining our design prototypes. Second: manufacturing. When it came to selecting clinical-grade materials, the appropriate engineering methods, manufacturing tools and processes, and ensuring adherence to regulatory standards, we’ve had to turn to other small-to-medium enterprises (SMEs) to help us out. We are pleased to be working with Contamac in the UK, one of the leading IOL and contact lens material experts, on developing our material for this lens, and our manufacturing partners include specialist companies in France and Spain, both with extensive expertise in IOL and corneal device engineering and prototyping. We are also working with the David J. Apple Laboratory in Heidelberg – which has world-renowned IOL testing capabilities – to provide independent efficacy results.Hakam Ghabra is CEO and founder of MAG Optics Ltd. He is a cross-specialty practicing surgeon at University College London, UK.