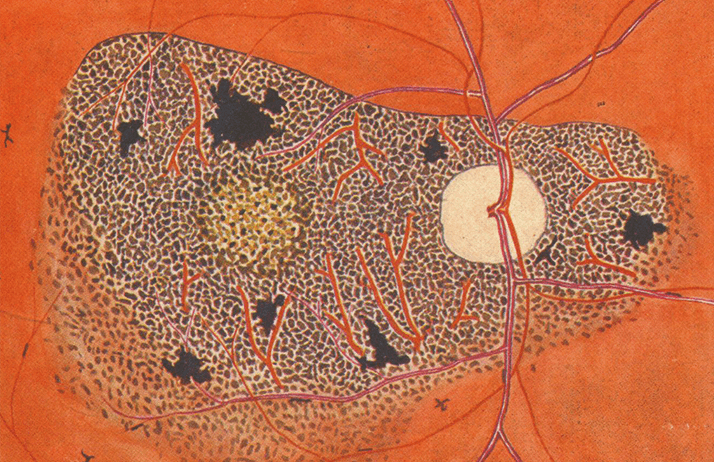

Harold Ridley’s other claim to fame is his research into River Blindness when stationed in the Gold Coast (now Ghana) in 1941. He spent a fortnight in Funsi, in the Wa East District of the country, with a battery-operated slit lamp, diagnosing and characterizing the ocular symptoms of River Blindness (Figure 1), which was eventually published in his landmark monograph, “Ocular Onchocerciasis” (1).

Contracting the disease is a disaster for patients and is one of the leading causes of preventable blindness in Africa. Infection is spread by the black fly, and is caused by the parasitic worm Onchocerca volvulus. Diagnosis and treatment is the key to prevention, but the first part can be a challenge. Although Ridley could see worms in his patients’ eyes, not all patients with onchocerciasis present in this manner. The gold-standard diagnostic test is a skin snip followed by examination of the snip in saline solution. If worms appear: the diagnosis is made. If worms don’t appear, this doesn’t give the patient the all-clear: DNA extraction and PCR screening for the worm’s genes has to then be performed.

Antibody tests would appear to be the answer – a fingerprick, drop the blood onto a immunochromatographic assay (just like a home pregnancy test) and get a result in under 20 minutes. That’s just what PATH, an international nonprofit organization have managed to develop in combination with the (US) National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: the SD Bioline Onchocerciasis IgG4 rapid test. David Kaslow, PATH’s vice president for product development explained why they thought this could be a game-changer: “The proven technology behind this test makes it a powerful and reliable tool in the multinational collaboration to eliminate river blindness. The availability of a rapid, point-of-care diagnostic is a harbinger of a world free of the suffering caused by this insidious parasite. What’s needed now is quick action to add this simple test to control and elimination programs.”

The US’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, however, published statements that are less effusive, stating “These tests cannot distinguish between past and current infections, so they are not as useful in people who lived in areas where the parasite exists, but they are useful in visitors to these areas” (2). It’s not a bug, it’s a feature, say PATH: “By detecting unique antibodies to the parasite, it quickly identifies previous exposure” (3). Given that Merck has promised to supply the treatment – the oral antiparasitic drug, ivermectin – free of charge to affected areas until the disease is eliminated, that could represent a significant chunk of people with positive-tests. Perhaps that’s not the point. Although River Blindness has been eliminated from many regions of Africa (4) and many people have been successfully treated with ivermectin – many have not. Screening patients with a method that doesn’t require skin biopsy puts fewer people off, and if that method that is both rapid and reliable, can only be an asset in the field. It should definitely aid screening – and as that’s the first step on the path to eliminating this pernicious disease, it’s certainly a commendable endeavor on the part of PATH and its partners.

References

- “OCULAR ONCHOCERCIASIS Including an Investigation in the Gold Coast”, Br. J. Ophthalmol. 29(Suppl), 3–58 (1945).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites – Onchocerciasis (also known as River Blindness). Updated May 21, 2013. Accessed November 25, 2014.

- PATH “New test will combat major cause of preventable blindness in Africa”, Press Release, November 2, 2014. , accessed November 25, 2014.

- K.L. Winthrop, J.M. Furtado, V.C. Lansingh, “River blindness: an old disease on the brink of elimination and control”, J. Glob. Infect. Dis., 3, 151–155 (2011). doi:10.4103/0974-777X.81692.