What prompted you to research Charles Bonnet Syndrome?

I have always been fascinated by Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS). I have worked in low-vision clinics for about 20 years, and I pretty much ask everybody I see about it because patients don’t generally volunteer the information. It’s associated with a lot of stigma, so I proactively ask people and, through doing that, I have come to realize that more people have CBS than is often reported.

Additionally, our understanding of CBS and the underlying mechanisms are not that much further along from when I was first taught about it at university – or even from the first descriptions of the syndrome by Charles Bonnet himself in 1760!

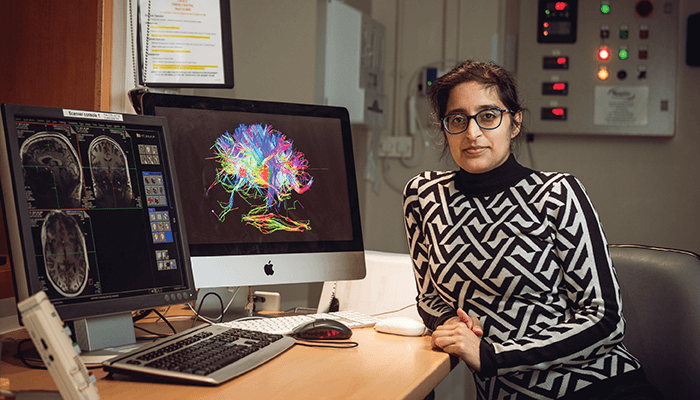

As it occurs across all eye diseases and manifests in the same way (regardless of what is happening at the level of the eye), it is clearly happening further along in the visual pathway – in the brain. As I completed my PhD in neuroscience, I realized we have more tools available to potentially understand CBS. Indeed, I think CBS research has been stifled in the past simply because it happens in the brain, so the tools needed to study it are beyond the scope of most people who study eye disease. In other words, we need to get neuroscience researchers interested. I’m addressing the gap by collaborating with two neuroscientists – Betina Ip and Holly Bridge – to build on the knowledge and the work of other people, like Dominic Ffytche. We’re also harnessing new tools, such as advanced MRI methods, that can probe different aspects of brain function to try to put the last pieces of the jigsaw in place. Once we know where in the brain it’s happening and what exactly is happening, we can get more professionals outside of ophthalmology and optometry to take it seriously, while providing a foundation for more targeted therapies.

How did your previous paper direct your current research?

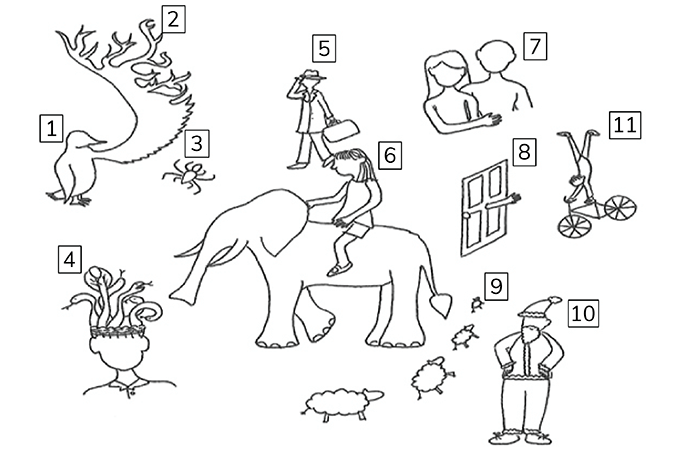

Our first paper was the result of a project that aimed to bring together all of the different theories about what was causing the hallucinations experienced in CBS (1) – the range of which are demonstrated in figure 1. Several theories focus on imbalances in neurotransmitters; one reasons why vision works so fast is that alongside feed-forward (the signals coming up from the visual system), we also have feedback coming from the higher visual areas – in essence from our memory – that fine-tunes the signal, enabling the visual system to respond much faster to visual stimuli. One theory of particular interest to us is that CBS is a result of the imbalance between what’s coming in from the visual system and what’s coming from upstream. Given the low vision of patients with CBS, there isn’t much feed-forward – but the feedback is still occurring, which is being seen in the form of hallucinations.

We are now probing these mechanisms at both the University of Oxford and Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. At Oxford, we are running a study that uses MRI to observe the activity and levels of neurotransmitters in people with CBS compared with people without; at Cambridge, I’m working with Jane Aspell using EEG to look at brain activity, before, during and after the hallucinations. Though they are different studies, they are also very complementary. When we put the results from both studies together – alongside previous research from other teams – we hope to build a more comprehensive picture of what’s actually happening in the brains of people with CBS.

Why do you feel this kind of exploratory research is so important in CBS?

I’ve heard some real horror stories of patients being admitted to psychiatric wards or being dismissed by non-ophthalmology doctors to whom they’ve gone for help. We need to stop that from happening.

If you look at the history of medicine more widely, there are many conditions that have not been taken seriously until the underlying physiological mechanisms have been proven. Epilepsy was originally considered a psychiatric disorder until the brain imaging showed otherwise. Myalgic encephalomyelitis was disbelieved – and still is in some quarters – but now there is brain imaging to prove that it’s real. Dyslexia was dismissed until the brain imaging showed that there are actually physiological changes. There is a clear repeating – and disturbing – pattern here. In fact, I think there’s a greater conversation to be had. I don’t think we should place so much emphasis on proof if it means ignoring patients and their symptoms.

Of course, we take CBS seriously in ophthalmology and related professions but, across medicine, there’s very little awareness of CBS and I really want to be able to change that by pointing to a solid evidence base. We want to reach the end of our studies and be able to say, “Look! Here’s the evidence. It’s real.”

How can other ophthalmologists help?

Actively asking whether patients experience images that they know aren’t really there is crucial, as it’s a clear sign of CBS; patients know that their hallucinations are not real. If people report that they do see hallucinations, explain what they are, offer reassurance, and ask if they are interested in taking part in research. There are quite a few of us doing research into CBS – I’m still recruiting patients and there is another study from City University that is currently recruiting for a questionnaire study ahead of an interventional study.

Twitter is always a good source of information about studies. For example, Esme’s Umbrella, the charity for CBS, puts out regular calls for recruitment for research studies across the globe. And if you don’t have Twitter, you can always email them.

Our Oxford study has a referral email address: brain@eye.ox.ac.uk. And referrals for our Cambridge EEG study can be sent to my post-doctoral researcher: bethany.higgins@aru.ac.uk. As some of the funding for our studies comes from the NHS, we can only accept UK patients – but the online, questionnaire-based studies usually have more global reach. Again, Judith from Esme’s Umbrella will be able to advise what’s open to different regions and help in that regard. Additionally, clinical trials and interventional studies are registered on www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Can you share any preliminary findings from your ongoing research?

Unfortunately not – we need more patients! And so, to repeat, if the community can help us find a few more participants in the next couple of months, we will hopefully have results to share by the summer – and that would be amazing!

References

- K Carpenter et al., “The elephant in the room: understanding the pathogenesis of Charles Bonnet syndrome,” Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 39, 414 (2019). PMID: 31591762.