Ophthalmology is a very visual specialty. Unlike other internal medicine or general surgical specialties, we can recognize disease in the eye rapidly by simply looking for unusual dots, lines, and shapes that could represent pathology. Clinical photography/video is therefore the fastest way to gather, absorb, and share clinical information. We all know about retinal pictures, corneal photographs, eye positions in nine gazes, etc. Why then, is rich media data not more embedded within modern ophthalmology documentation?

If we all recognize the utility of clinical photography, why are we still treating patients without capturing photographs routinely for every single patient with a visible sign?

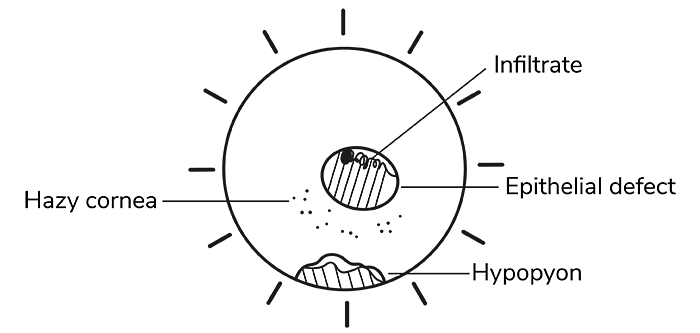

Figure 1

Figure 1

Table 1

Right eye | Examination |

|---|---|

conjunctival hyperaemia + | Conj/sclera |

hazy cornea central round defect with peripheral infiltrates | Cornea |

hazy view 1mm hypopyon | AC |

If you have moved to an electronic patient record (EPR), you’ll notice a trend in how we document clinical signs. We have moved from a quickly drawn diagram to a hastily typed description (Table 1), which arguably takes more time to type, yet carries less information.

What other industry in the world would accept this level of regression in quality?

Despite the drawing tools offered by EPRs that enable annotation and color filling, clinicians don’t seem to use them to their full potential. Simply put, it takes too long – no one has the time for drawing tools in a busy clinical practice.

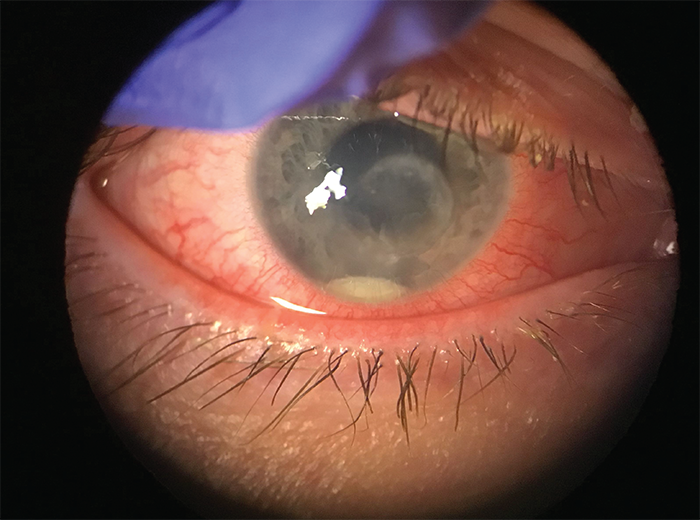

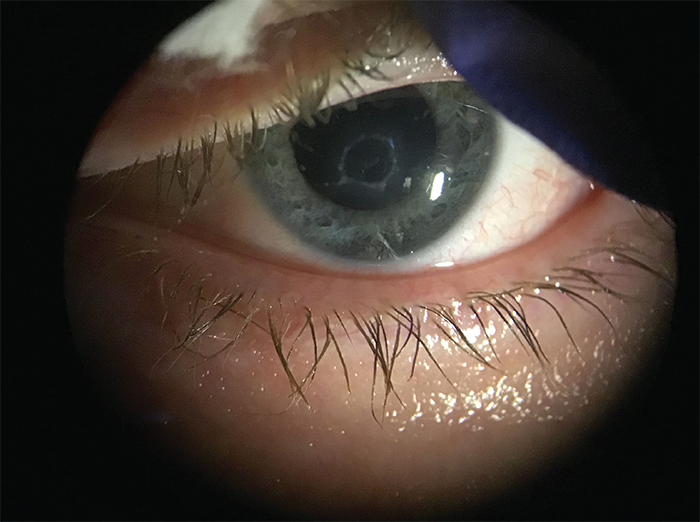

Photographs, on the other hand, carry much more information and can be quickly interpreted. In Figure 3 we see a case of a contact lens related corneal ulcer. Figure 4 shows the eye a few weeks later following treatment. The central epithelial defect has closed, the hypopyon has subsided, the circumferential conjunctival injection has resolved, and the cornea is now more transparent. A clinician would be able to obtain all that information within a split second without any detailed description necessary.

So, how do we streamline the process of documenting clinical signs?

Very simply, photographs should be taken at every follow-up, or at least at relevant intervals. Don’t waste time with hand-drawn diagrams or computer-drawn diagrams if a photograph is possible and, most importantly, don’t overly rely on text-only descriptions on the EPR (using vague and broad comments like “epithelial defect healing”). Using a text description to describe a visually appreciated sign if you have access to an anterior segment camera is like using your fingers to palpate intraocular pressure when you have access to a Goldmann tonometer.

So, why are we so poor at incorporating clinical photography? Let’s explore some possible reasons, and discuss why they are no excuse for not adapting to advancing technology.

1. Inconvenience

As it stands, it is “easier” to examine a patient and scribble a few notes down than to capture a photograph, which requires more time and labor. This is a false economy – when a patient returns, the clinician may be unsure if the patient’s condition has worsened, improved, or stayed the same because of inadequate notes. It seems unethical to compromise on care this way, particularly when the technology is so accessible. Clinicians will inevitably move away from pen and paper as the primary medium for medical notes. As technology continues to advance, clinical data must also evolve.

2. Costs

Clinicians may assume that they need to spend lots of money on a high-quality camera for ophthalmic imaging, but this is not necessarily the case. Lower-cost alternatives can work just as well – these include smartphone adaptors for slit lamps, digital SLR cameras, or 20 Diopter condensing lenses for magnification. As smartphones continue to improve, the quality and portability of makeshift slit lamp cameras will scale up even more.

Apart from anterior segment pathology, which would traditionally require high magnification, there are subspecialties that do not require slit lamp expertise, including oculoplastics, strabismus, and neuro-ophthalmology. This means that office-based clinical photography should be very achievable.

3. Inadequate optics for minute detail

The optics of the slit lamp may not be successfully captured by a camera. This means that minute detail, such as that found in the corneal guttata, is hard to capture. There may be details of cells or flare or opacities that are not easily captured but are much more readily seen via the gold standard examination techniques. Although, admittedly, photographs will have their limitations in these situations, they are still able to capture associated positive or negative signs. As technology advances, we can start to expect better optics. Clinical photography particularly in ophthalmology is also an art form. The more we practice, the better we get at capturing detail.

4. A weak digital infrastructure

The problem with EPRs is that they are designed to act as a substitute for paper when really they should be revolutionizing the paradigm of medical documentation altogether.

Paper is “comfortable” because it is a fast and unstructured way to store information, especially when it comes to drawing diagrams. EPRs, on the other hand, are structured and rigid databases for storing patient information. Even if a clinician has access to a tablet on which they can “draw,” the number of clicks required to get the drawing tool in the right place is so tedious that users prefer to settle for the bare minimum. The more EPR tries to replace paper by emulating paper the more it will keep running into the same user dissatisfaction issues. This is why some clinicians can use an EPR for a decade and still feel that paper is “faster.” It might not be objectively much faster in terms of seconds and minutes, but it can feel psychologically easier.

5. Culture change

A particular fear is that, inevitably, by depending more on photography/video data, we will lose the art of describing lesions. However, I am not sure if this is all that relevant. Human skill sets evolve all the time. When the advent of the calculator, a whole generation lost a degree of skills in mental arithmetic – but equations could now be figured out much more quickly and accurately. Similarly, patients don’t really care how good you are at verbally describing a lesion if a photograph is the best option to relay clinical information.

It is clear that, culturally, we need to change our approach when it comes to recording ophthalmic clinical signs. Let’s ask ourselves, in the digital age, should we bother with drawing diagrams at all? Every eyelid, cornea, anterior segment, retina, and even strabismus can now be photographed. What does a drawing (paper or digital) add that a high-resolution color photograph doesn’t?

Medical education is archaic in nature. It sticks to tradition and is slow to change. The first medical school was founded in 1220; the first color photograph was taken in 1861. It makes sense that physicians had to learn how to draw accurately. What if the dates were the other way around, and color photography started 600 years before the first medical school? Would physicians have bothered drawing anything?

Making ophthalmic decisions in 2023 without optimizing every tool in our arsenal is a disservice to our patients. Using clinical photography and video to document clinical signs should no longer be thought of as an adjunct – instead it should be the primary form of note keeping. As we evolve into a new digital age led by artificial intelligence and Big Data, clinicians should also evolve in their mindset when it comes to documentation.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 4