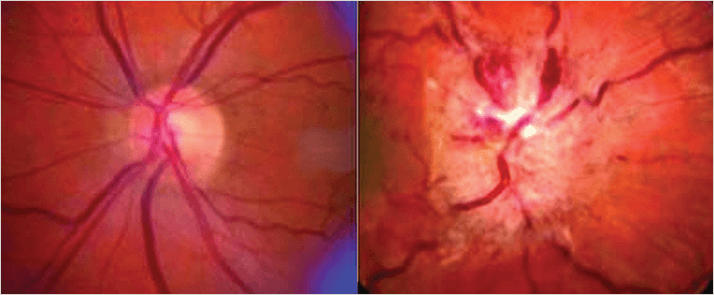

Formerly known as benign intracranial hypertension, uncontrolled idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a far from gentle condition that occurs mostly in women and is linked to obesity. The headaches, tinnitus and vomiting are unpleasant enough but the ocular symptoms are most serious. Increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in patients often compresses the sixth cranial nerve, resulting in problems with abduction (looking away the from midline) of the eye and double vision. Swelling of the optic disc (papilledema) can occur (Figure 1), causing transient vision obscuration which, if left untreated, can result in progressive and permanent vision loss.

Lumbar puncture to drain the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rapidly reduces ICP but only very occasionally does it resolve IIH. Weight loss is an effective treatment but it is hard to achieve and harder to maintain. Bariatric surgery works, but is costly, and waiting times are long. So the option that many doctors turn to is the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, acetazolamide (Diamox). Acetazolamide is not a drug prescribed lightly. It may reduce CSF and aqueous humor production, but it has many side effects, ranging from paresthesia, fatigue and drowsiness, to metabolic acidosis, hypokalemia and hyponatremia. Furthermore, the evidence that it worked better than placebo has been inconclusive (1). “The vision problems associated with this condition can be extremely debilitating, at significant cost to patients and the health care system. Yet there are no established treatment guidelines,” says Eleanor Schron, director of clinical applications at US National Eye Institute. “We made it a priority to develop an evidence-based treatment for helping patients keep their vision.”

To settle the matter, the Neuro-Ophthalmology Research Disease Investigator Consortium (NORDIC) team performed a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial that involved 161 women and four men with IIH and mild vision loss (2). Their average body mass index (BMI) was 40. All were instructed to trim salt and about 500 to 1,000 calories from their daily food intake, given weight-loss coaching, a pedometer and a rubber tube for use as a resistance band. Patients were randomized 1:1 to receive either acetazolamide or placebo; the drug was given at 1 gram daily for the first week and increased by a quarter of a gram each week, to reach the maximally tolerated dosage, or up to 4 grams daily. Placebo “dose” was also administered in the same manner. After six months, compared with those receiving placebo, patients receiving acetazolamide displayed a greater reduction in optic nerve swelling, and twice the improvement in visual field tests, as well as greater improvements in daily function and quality of life. Six treatment failures involving substantial worsening of vision that required withdrawal from the trial occurred in the placebo group, with only one such event in the acetazolamide group. And seven people on acetazolamide and one person on placebo stopped taking their assigned study medication because of perceived side effects, and all side effects were reversed by stopping the drug or reducing the dosage.

Lead author, Michael Wall of the University of Iowa, said that the study “provides a much-needed evidence base for using acetazolamide as an adjunct to weight loss for treating IIH,” noting that the “Strength of our study is that we slowly introduced patients to the highest tolerated dose, in an attempt to maximize efficacy while limiting its side effects.”

References

- A.K. Ball et al., “A randomised controlled trial of treatment for idiopathic intracranial hypertension”, J. Neurol., 258, 874-881 (2011). doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5861-4. M. Wall, et al., “Effect of Acetazolamide on Visual Function in Patients with Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension and Mild Visual Loss: The Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial”, JAMA, 311, 1641–1451 (2014). doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3312.