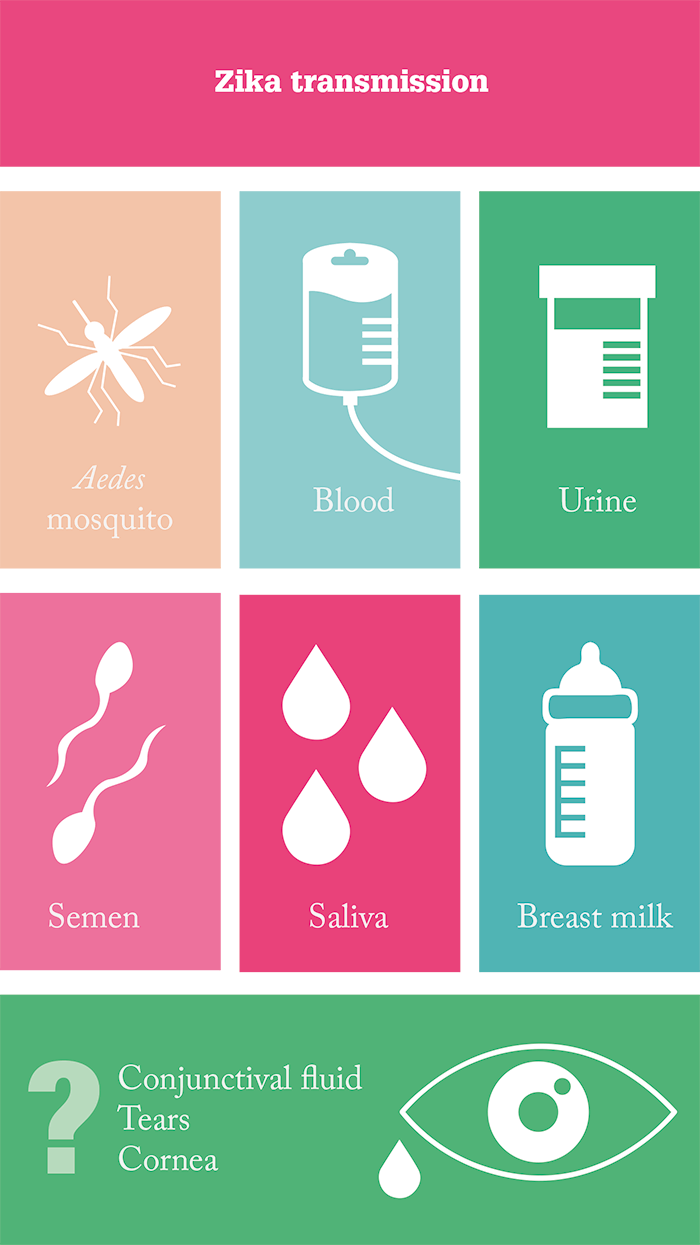

Aedes mosquitoes are on the march. Formerly confined to tropical areas, a combination of climate change and evolving to cope with the cold has meant that these mozzies have been found as far as Washington DC and Heijningen in the Netherlands. The problem is, they spread the Zika virus (Zika). Zika infection usually isn’t the end of the world – it’s commonly symptomless, but if there are symptoms, they’re usually flu-like, sometimes with a rash, and over within seven days. However, occasionally Zika can cause Guillain–Barré syndrome in adults, and infection in pregnant women can sometimes lead to babies being born with microcephaly, other brain malformations, and occasionally ocular deformities too. Curbing its transmission (by mosquito and the other major route of transmission, sex) is therefore a top global health priority.

Little is known about how the virus enters the eye and what harm it may cause – but it turns out ocular tissue might play a role in Zika transmission. “Many isolated reports of infants with ocular abnormalities have been attributed to Zika because their mothers were infected during pregnancy,” explains Rajendra Apte of Washington University, St Louis, Texas, “but causality has been unclear as some findings can be seen without the virus.” To clear up the confusion, Apte et al. (1), “wanted to model, in mice, Zika infection during pregnancy, in neonates and in adults, to assess whether the virus directly affects the eye, and what damage it may cause.” Zika doesn’t replicate in mice – it can’t replicate, as (unlike in humans), it can’t antagonize murine STAT2, a downstream signaling component of type I interferon [IFN] receptors. The answer? Inoculate transgenic mice that can’t signal through the type I IFN receptor. By doing this, they found that Zika infects the cornea, iris, optic nerve, and retinal bipolar and ganglion cells in adult mice, all within seven days of inoculation. The team did not observe evidence of ocular abnormalities in congenitally-infected fetuses and pups – but they did find viral RNA in both the lacrimal glands and tear fluid of the mice (1). “We did not expect to find virus RNA in tears, as this is not seen with other viruses such as Ebola,” remarks Apte.

Thankfully, the tears weren’t capable of causing infection – but ocular homogenates were – and took just 10 days to kill mice that were inoculated intraperitoneally. Apte observed that there is “potential for the virus to use the eye as a reservoir.” Next steps? “To test human patients to see if there is evidence of the virus in tears, and to assess the implications of our findings for corneal transplantation.” It turns out that, thanks to recently published findings (2) from the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention (China), there is already evidence suggesting that the virus is present in the conjunctival fluid of infected human patients. Zika was found in conjunctival swabs taken from six patients with laboratory-confirmed cases of infection, as determined by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction. What does this mean for ophthalmology? It may be a small risk, but it does look like there’s a real potential for Zika transmission via corneal grafts, and perhaps also during eye surgery.

References

- JJ Miner et al., “Zika virus infection in mice causes panuveitis with shedding of virus in tears”, Cell Rep, [Epub ahead of print] (2016). PMID: 27612415. J Sun et al., “Presence of Zika virus in conjunctival fluid”, JAMA Ophthalmol, [Epub ahead of print] (2016). PMID: 27632055.