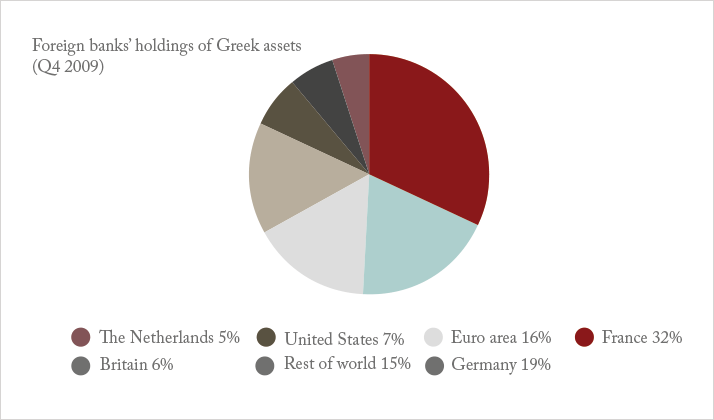

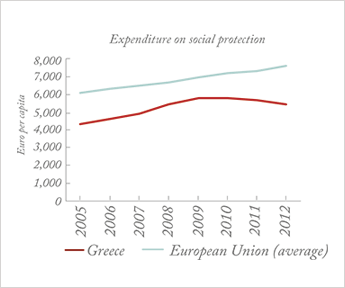

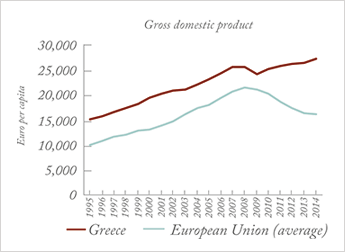

It’s common knowledge at this point that Greece is, to put it succinctly, in trouble. In February 2010, Greece’s then Prime Minister, George Papandreou was faced with a problem. Elected only four months previously, he had discovered that for most of the previous decade, the country’s debt statistics had been misreported. Instead of having a deficit for the year of 2009 of around 6–8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), the reality was that it was nearly double at 15.7 percent – the highest of any European Union country that year. He came out, and told the truth. What followed was a modern day tragedy. Greece couldn’t devalue its currency – the Euro was not theirs to devalue, and for that matter, a large proportion of their debt was owed to private banks in other European countries that also used the Euro, principally France and Germany. Another option was default – something that was thought would break the Euro as a currency. What happened instead, was a bailout. On May 2nd, 2010, the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – also known as “the Troika” – stepped in with a €110 billion bailout, but with the following conditions attached: the implementation of structural reforms, privatization of government assets, and crucially, austerity measures.

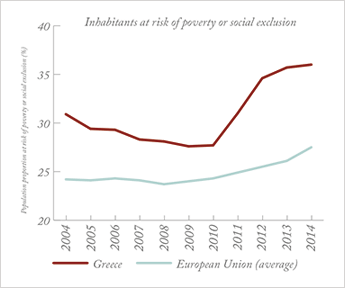

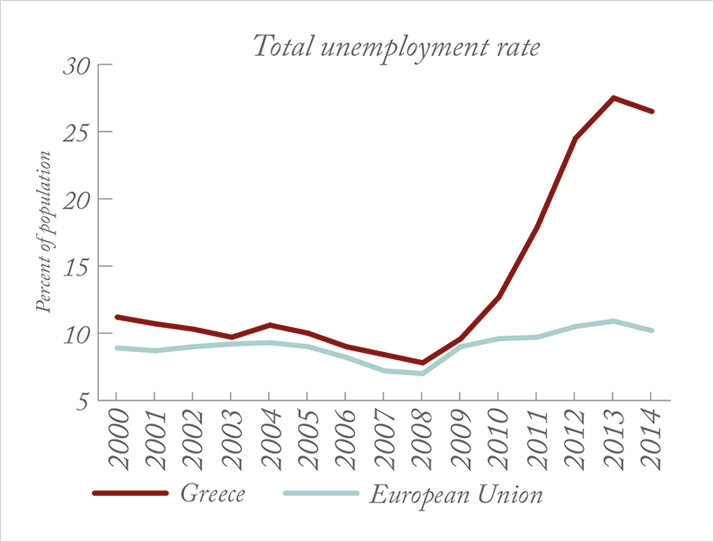

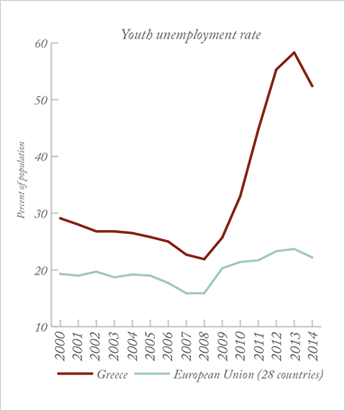

But instead of saving the Greek economy, those measures just made things worse. The economy tanked, and with it, the chances of Greece repaying its loans. From there, the tragedy continued to unfold. A high-speed vortex of credit resulted in a second (€110 billion), then a third (€240 billion) bailout. The circumstances before that third bailout, in July of this year, were dire: you had a developed European country where the main breadwinners in many families were grandparents, solely because they happened to draw a pension, and youth unemployment was at a rate of 60 percent. Rumors of “Grexit” – the withdrawal of Greece from the Euro and reinstatement of the Drachma – and devaluation abounded; capital controls restricted Greeks to €60 a day in cash withdrawals, with foreign cash transfers being banned. Later, bank holidays were enforced. Credit had come to a standstill, and with it most commercial and governmental activity. This happened to also include healthcare – a need that exists every day, irrespective of the prevailing financial conditions. The Greek state healthcare system was struggling, and the private healthcare system was shrinking fast. The capital control measures only served to make the situation worse: imports of pharmaceuticals and other products stopped, hence the news reports of pharmacists running out of drugs at the time. The longer this lasted, the worse it became for patients in need. If you required an urgent corneal transplant where a cornea had to be imported from a foreign tissue bank, or if you were among the many older people whose retinopathies make them reliant on a monthly anti-VEGF agent injection to maintain vision, then you were likely out of luck. And the longer you went without, the worse your risk of permanent vision loss became.

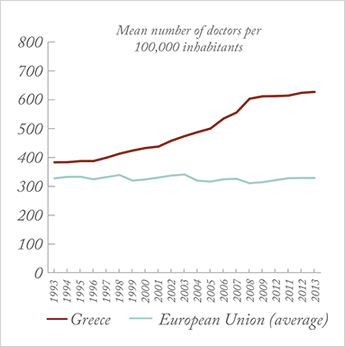

The banks were bailed out for the third time this past July. They reopened. Capital controls were relaxed. Greece began to function once again – but with yet more added austerity. But none of the fundamentals have changed; no debt has been forgiven. The chances are that this modern European country will go through the same calamity again, with no guarantee of a fourth bailout. But what of the impact of this July hiatus? What are the long-term health economic consequences of an increasingly morbid population – and visual impairment has one of the greatest health economic impacts, not just on healthcare systems, but on society in general. It’s this economic impact of vision loss that justifies the widespread deployment of high-cost interventions like anti-VEGF therapy and cataract surgery. There’s also the phenomenon of brain drain to consider. If you’re a highly educated ophthalmologist working in austerity-ridden Greece, you certainly know that you can earn better wages for yourself and your family elsewhere. Nobody could fault you for moving to a different country to work for the sake of the future of your family, but the consequences for Greek healthcare, however, are obvious. With recent influxes of refugees escaping war in Syria and Afghanistan by fleeing into Greece – many with health problems of their own – and precious little in the way of resources to deal with them, the country is ever more burdened with the healthcare needs of a population it cannot support. Ophthalmologists and their patients are feeling this imbalance of supply and demand as keenly as any discipline. So, given the situation, and in order to understand the impact austerity has had, and will continue to have, on the practice of ophthalmology in Greece, we spoke with an ophthalmologist with a unique – and transatlantic – perspective on the situation: the Athens- and New York-based titan of ophthalmology: A. John Kanellopoulos.

It is incredible that before 2009 Greece was one of the biggest healthcare markets in Europe. Yes, I am aware from personal communications with Alcon Laboratories that Greece was their fifth largest market in the European Union. This is quite a remarkable accomplishment, as they sell only ophthalmology materials, so one can only imagine the plethora of services they must have sold in Greece. It was my understanding that at the time, there were almost 35 excimer lasers in Greece, with about 30 centers providing refractive surgery services. In general, I think eye care in Greece at the time was at the top of its game with both the private and state sector offering the same as any other major European country. When and where did the effects of the budget cuts start to be felt? In the private sector. Almost immediately after the austerity measures were imposed in 2010–2011, there was a significant shift of patients from the private doctor’s office to the state system, which was provided free of charge to every Greek citizen. In our center we saw a significant decline in refractive surgery cases for the year 2012.

How long did it take before patient care started to suffer? It is hard to tell because there are no statistics on this, and there’s no specific watchdog that oversees the level of care, so this is a very arbitrary answer on my behalf… We get about 12,000 patient visits a year in our center in Athens where seven physicians collaborate in a multispecialty ophthalmology practice. After 2010 – and specifically after the second bailout in 2012 – there were significant shortages of materials in state hospitals and this really delayed patient care in those hospitals. For instance, many hospitals required patients to buy their intraocular lenses privately for the surgeon in the state hospital to perform cataract surgery. Specialty intraocular lenses essentially became contraband in state hospitals – only basic intraocular lenses were provided. Multifocal and toric lenses have therefore not seen significant clinical use in state hospitals. Nevertheless, the private sector has managed to survive, function and make a sufficient level of investments in new technology. The waiting times for state hospitals for cataract surgery at some point may have reached three months from essentially no waiting time before. However, as far as the private sector was concerned, there was no real change in waiting times. Before the third bailout was announced in July what was the situation like? Grexit was rumored, capital controls were in place, and the banks were closed. There were stories of drug imports being stopped and drug rationing. Did this directly affect eye care provision? Of course. The whole country froze at the end of June 2015 when all of a sudden capital control on banks were announced; essentially banks were closed for all business and every Greek citizen was only able to withdraw up to €60 a day from ATMs. We saw a sudden freeze in many procedures. We had the very awkward situation of having to perform an urgent corneal transplantation in a patient with corneal perforation and the capital controls meant that the patient could not transfer money to the International Eye Bank that would send the tissue in. We had to personally intervene and managed to have the patient reach the International Eye Bank through an international banking account and were able to successfully proceed with the procedure. Greece does have the Hellenic Transplant Organization, but despite the fact that the introduction of capital controls was not a surprise (it had been discussed for about six months before they were imposed) no contingency measures had been put in place. So it was very difficult for two-to-three weeks until the third bailout was put in place.

Did people lose vision because drugs or procedures were unavailable? Yes, indeed. It is very unfortunate that many people weren’t able to pay for some of these medications – and for others, some of these medications were simply not available over those three weeks, and, of course, there was no provision in place for these materials being made available through emergency funds. By example, we had to apply to a bank to request funds for a specific and necessary medical instrument. We gave them the details of what the instrument was, and why it was needed as soon as possible – and we only got a reply from the bank two weeks later! One can imagine how that can affect a medical practice that often deals with urgent medical matters. I am hoping that the amount of morbidity elicited to the general population in Greece from tragic weeks this last July was not large, but I am embarrassed to have witnessed this in our practice. We became very lenient on patient charging, and, of course, we offered a very large number of anti-VEGF treatments free of charge until the situation had stabilized. But, nevertheless, this is a small drop in the ocean, because healthcare altogether was at a standstill. If one considers specialties beyond ophthalmology – such as vascular surgery or orthopedic surgery, where prosthetics and high-grade materials are absolutely necessary – this becomes a disaster story. As a matter of fact, even now, almost three months later, capital controls have not been entirely lifted, and we have a tremendous issue in importing goods from providers not just in the European Union but also around the world. It is still rather difficult to transfer funds from any Greek bank that our center uses to a non-Greek provider. We hope that this will resolve soon.

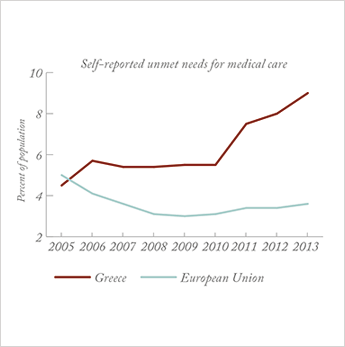

What was the impact on your patients? The biggest impact could be felt in our urgent cases, such as penetrating keratoplasty, retinal detachment repair, and the use of anti-VEGF drugs in an urgent situation such as diabetic retinopathy, choroidal neovascularization, and vascular occlusion incidence. What is the ultimate impact of reduced eye care provision on the Greek populace? We are aware of thousands of patients that have cut back on routine and preemptive eye evaluations and it is shocking to me, as a practitioner of the last 25 years, both in the US and in Europe, to consider how much morbidity could be avoided in these patients if the situation was improved or if there was a provision for it not to affect as much medical healthcare. Of course, as I mentioned, healthcare in Greece is not only private, there is also a relatively good state system, which is currently overburdened with thousands of illegal immigrants swamping Greek hospitals. They are, of course, treated based on their needs. Added to this is a humungous shift of middle- and working-class patients from the private sector into state hospitals, which is creating a truly chaotic situation. It is very depressing to see a very large state institution turning basement storage areas into 60-person hospital wards divided by cardboard – an image that would not be suitable even for veterinary care. So the truth is that healthcare in Greece is suffering significantly. There are a huge number of doctors that have not been paid by the state sector for years now, despite the very energetic attempts by the local medical boards and especially the Medical Board of Athens – and they have shown tremendous patience. Pharmacists the same, but, of course, we healthcare providers must always put patients’ care first and always compromise our personal reimbursement towards the best care for our patients. But the truth is that healthcare today is nowhere like where it was five years ago, and we hope the further austerity measures will not make the situation worse.

As a doctor how frustrating is it to see patients with treatable or manageable diseases lose vision because of factors outside your control? This is a very tragic question. It is devastating to me to not be able to help in an effective way. Of course, each one of us is doing the best to our abilities to help as much as possible and to provide the best care possible given the circumstances. What has been the impact on society? There is clearly a big lost productivity problem waiting as a consequence of austerity-degraded healthcare. Can you speculate on what this might do for the Greek economy of the future? I am afraid that the question is self-explanatory, because by reducing funding in healthcare and pharmaceuticals, it is a priori expected that healthcare services will be reduced in efficacy and reach. In my mind, there are two key factors that have to be addressed; the first most tragic one is the tens of thousands of illegal immigrants that are flowing into Greece from its very vulnerable boarders – mainly the Aegean coast with Turkey. It is impossible to control all these thousands of miles of border where a Greek island may be just a couple of knots away from a Turkish coast and people may be ferried even on jet skis from Asia into the European Union. This is creating a huge humanitarian crisis as these people flood boarder islands of Greece and they overwhelm the abilities of the Greek state to be able to process and manage them. The second part is the Greek citizens themselves. It is obvious that their choices are limited and the level of care is, of course, restricted as well. But I think that the most dismal consequence of this is the reduction of preemptive and preventive healthcare. As a corneal surgeon, I was hoping that corneal imaging for keratoconus would be available to any teenage Greek student and with the advent of collagen cross-linking, we could eradicate keratoconus in Greece. All Greek colleagues are aware of early keratoconus diagnosis and have access to providing their patients with a collagen cross-linking procedure, but all of these austerity measures have meant that a very large fraction of the population will not seek preventive care, will not have these preventive images taken. As the state system which is overwhelmed and the private system is becoming out of reach for many of these patients, this creates a massive morbidity issue for these patients in the future, and, of course, huge ethical questions of whether managing state and European Union finances is a “game” that will affect the wellbeing of thousands of young people in the future and probably permanently scar their lives, both emotionally and practically.

With one part of Greece’s population being unemployed, many families are relying on pensioners as their main breadwinner in spite of the fact that pensions have been cut, and healthcare budgets reduced... Is it having an impact on clinic volume? Of course. We usually perform cataract surgery in Greece at the age of about 75, so all of these patients are pensioners and pensions being cut significantly will limit, and has already limited, their access to healthcare. Are people losing vision or going blind because of this? Of course, and I think if these numbers were explored and processed by the proper authorities, the results would be extremely dismal. Are people missing appointments because they are unable to afford public transportation to hospitals? Yes, indeed. This is also a significant deterrent for patients who live outside the major civic centers. Remember, Greece has hundreds of islands and transportation from these islands – which have extremely basic healthcare state facilities available to them, is limited and very costly – especially in the summer where the island transportations, both by sea and air, is overwhelmed by the huge surge of tourists. There’s apparently fail-safes built into the system to deal with people without healthcare insurance, but there are many stories stating that hospitals just aren’t equipped to deal with those patients and turn them away. Is there a demographic that essentially has no access to eye care or healthcare at all? Yes, indeed. Although healthcare in Greece is free for every Greek citizen, many hospitals are overwhelmed by the number of patients that they see and are sometimes understaffed and, over the last year, significantly underequipped with state-of- the-art equipment that could substantially improve the healthcare of these patients.

Is “brain drain” becoming a reality? This is another odd situation. I am aware of a lot of ophthalmologists that have already left Greece for a country within the European Union or the Middle East, in order to seek employment. I am aware of many physicians, some of whom are exceptionally well-trained (and with long-established practices) that have already left the country for either another EU country, the US, or the Middle East. I think this is having a significant demoralizing impact on the remaining doctors. It is very costly for a country like Greece to train physicians – and I am proud to say that the level and expertise of Greek physicians is outstanding – just to see them leave for another country. The loss is tremendous both on the social level, the scientific loss from the Greek scientific community, but also the financial loss of these people that have provided training for physicians; medical school training in Greece is provided by the state. What is stopping the remaining doctors from leaving? Obviously, it is very difficult for a physician to become a financial refugee. There are still family ties. Greece is one of the most vigorous countries in enjoying close family ties and very tight families, so this is a major deterrent factor. On a lighter note, Greece is a beautiful country to live in so I cannot imagine that someone would take the decision to leave Greece lightly. What will be the consequences on Greek healthcare in a decade’s time? I am afraid that Greece will go years back in healthcare expertise, equipment, and the availability to every Greek patient in every part of the country. We are hoping that things are not going to turn out as bad as we expect them to, but based on all these observations, this is my fear. Has the third bailout improved things? No, although emotionally people may feel relieved that Greece is not in the headlines anymore. I remember one day that the Greek financial situation was five out of the seven subjects published by the Reuters Internet news service, which is quite impressive. Although the emotions of the Greek people have quietened a little bit, in practical terms it’s a different story: the capital controls are still in place, and further significant austerity measures are yet to come. So we have not seen any real-world improvement in the Greek economy other than tourism, which is currently at its peak, with millions of Grecophile tourists swamping all the Greek islands and the cities that carry the very heavy Greek heritage that most people in the world want to visit and experience.

So you believe another bailout is inevitable? Will it be worse next time? Yes, I think that over the last five years we have already seen two bailouts fail because there was no real correlation between the bailouts and fundamental changes in Greek infrastructure. I am afraid that even with this third bailout, personalities in Greece are tough to change and all the recipe of the results and things going wrong will be extremely hard to change. We are hoping that our political leaders will be even more vigorous in implementing these fundamental changes in the way the Greek state works in order to improve the finances and the economy in general. I am not an economist, but I have lived in Greece the last 14 years and we have experienced quite a change between the Olympics of 2004 and this last July of 2015. What can be done to mitigate the effects of the next battle between Greece and the Troika? Again, nobody knows. We are hoping that reason and logic will prevail both on the Greek side and on our European partners’ side, and that both sides will be able to maximize the benefits for Greece and for our European brothers and sisters, in order to have this beautiful country become productive, efficient, and a solid partner within the European Union. As it has been reiterated over and over – especially these last months in Greece – Greece is Europe and no one can imagine a Europe without Greece.

Watch the video interview here