Andrea Pregel

Andrea Pregel

As Global Technical Lead for Inclusive Health at Sightsavers, I have had the privilege of seeing the positive difference that accessible healthcare can make in an individual’s life. In Bangladesh, for example, where we ran our Right to Health project, we met a woman named Shamima who had hearing and speech difficulties, and relied heavily on sight to communicate – her family had even created their own sign language to communicate with her. However, Shamima’s vision was rapidly deteriorating, and she did not have the funds to go to an eye doctor to seek treatment.

Shamima’s sister heard about the free eye camp we were hosting and brought her along. She was attended to by staff who had been trained on disability inclusion, and she was referred for a free cataract operation. Shamima and her family were provided with accommodation and meals. This extra support is important; attendees are often very afraid of cataract surgery and some people with disabilities won’t have the operation if no one can accompany them to the hospital.

It was really moving to see how, following her cataract surgery, Shamima was able to continue communicating with her family in the way she was used to, and to see her daughter properly again. Her experience also encouraged her friends and family members to reach out for support with their vision. That is the power of accessibility.

Improvements needed

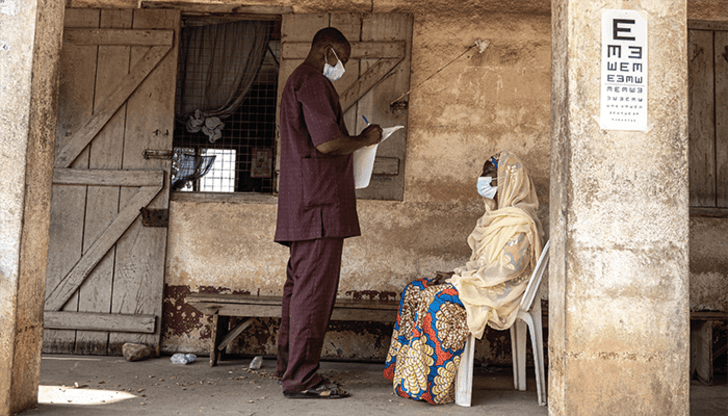

Accessibility is something that ophthalmologists should consider more in their daily practice. People who are blind and visually impaired experience many barriers when accessing health services. Navigating a health facility can be quite complex and sometimes dangerous; when spaces are not designed with accessibility in mind, they can become threats. Examples of this include shelves or other protruding objects that are difficult to detect for people using white canes, objects on the floor, or uneven surfaces that can become trip hazards. It is important to remember that anyone can develop eye conditions and may need access to eye care services, so accessibility is key.

Simple solutions can improve accessibility for people who are blind and visually impaired, such as ensuring that there are no obstacles in rooms and corridors. Using color contrast is important; color coding different parts of a building can help those who have some residual sight to move around more independently. The use of tactile floor tiles, tactile maps, large prints, and information in braille and audio formats can really make the difference for people who are blind.

Facilities need to be accessible to wheelchair users, providing ramps with gentle slopes and handrails every time there is a level change, alongside accessible steps – except, of course, to access different floors, in which case accessible lifts are required. Deaf and hearing-impaired people also face barriers when accessing services – particularly in terms of access to communication and information. Our partners in Nigeria shared the story of a deaf woman who remained in a facility for hours during the COVID-19 pandemic because she didn’t hear the announcement that the hospital had closed for the day. The use of visual information, including captioning in videos, installing hearing loops, and employing sign language interpreters are all solutions that can improve the experience – and ultimately the health outcomes – of many patients.

People with intellectual disabilities or neurodiverse conditions can benefit from information in easy-read formats as well as longer consultation times. Simple adjustments in terms of ventilation, lighting, noise reduction, and the availability of quiet spaces could make a difference for people with mental health conditions, psychosocial disabilities, or chronic health conditions. It’s also important that accessible toilets are built following specific standards. These are not a luxury but a basic right, and can truly influence access to services. People with disabilities have told us multiple times that, if they need to travel for hours to reach a facility, and then the toilet is not accessible, they often prefer not to go in the first place – meaning they remain excluded from basic health services.

It is also worth noting that people with disabilities, including those who are blind or visually impaired, often experience stigma and discrimination and are exposed to higher risks of violence and abuse. For example, women with disabilities who are involved in some of our projects shared experiences of being treated badly in health facilities when they tried to access sexual and reproductive health services. Staff did not believe that women with disabilities could, or even should, be sexually active or want to form a family.

Auditing accessibility

Accessibility is a fundamental component in all of our work – and all our projects invest in this area. One tool to help assess the accessibility of existing health infrastructure – as well as aid the development of national accessibility standards and guide the development of new health facilities – is Sightsavers’ accessibility standards and audit pack.

We wanted a tool to assess the accessibility of existing facilities in our inclusive eye health projects. Although we found a few resources, some developed in the past by Sightsavers and other partners, they did not really meet our requirements. And so, we decided to produce a new toolkit, specifically designed for our projects.

We started by reviewing accessibility standards from different countries. These tend to be complex documents aimed at architects and other professionals responsible for the design of the built environment, and they are not always easy to use with existing infrastructure. We drafted a simplified list of standards that we felt were relevant for health facilities and that could be used at project level by people who are not experts in this field, such as representatives of organizations of people with disabilities (OPDs) and managers of health facilities. Alongside the standards manual, we developed other tools, such as the checklist – which is crucial during an accessibility audit – and planning and costing tools to support the renovation of facilities following the audits.

We tested the toolkit at our project in Nampula, Mozambique, working closely with OPDs and government partners, and used the feedback and learnings to improve it. Subsequently, we worked with OPDs in Malawi, Bangladesh, and Pakistan to refine the standards and complementary tools, ensuring they were fit for purpose. We made the toolkit publicly available so that others could benefit from it. So far, the toolkit has been downloaded hundreds of times by researchers and implementers across the world. In 2022, it won a Zero Project Award (1).

Projects of progression

At Sightsavers our work across eye health overlaps with a lot of our other inclusion work, such as inclusive education, combatting disabling neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), and advocating for disability rights. We have trained more than 300 people on our accessibility auditing methodology – including representatives of OPDs, architects, engineers, and public and private health sector managers. We have audited more than 80 health facilities across countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, supporting the renovation of many of them. During the pandemic, we audited COVID-19 testing and treatment facilities in Abuja, Nigeria, helping make them more accessible for people with disabilities at a time when many were excluded from life-saving services. Our team in Pakistan also used the toolkit to audit the Parliament House, helping the National Assembly Secretariat make the premises accessible to people with disabilities.

In Tanzania, we also run the Boresha Macho project, which targets people who traditionally face barriers to accessing health care (2). We conduct health facility accessibility audits and upgrades, provide inclusion training for health professionals, and raise awareness with local disability organizations. So far, this project has provided eye care to 178,000 people who might have otherwise not been able to receive it.

We are currently running an inclusive family planning project in Kaduna, Nigeria, with BBC Media Action (3). The project aims to ensure that women and girls with disabilities can make informed choices about their reproductive health and access the services they need, based on free and informed consent and bodily autonomy. This is to combat the stigma and discrimination that exists around disability and sex. As part of this, we have used our toolkit to audit 24 public and private health facilities.

Both of the above projects in Nigeria were undertaken as part of Inclusive Futures, a group of more than 20 organizations working together to make international development include people with disabilities, which Sightsavers leads (4).

Although making existing health facilities more accessible is important, we recognize that sometimes it can be complex; incorporating accessibility in the design of new health infrastructure is critical and much more cost-effective. And that’s why we were pleased when the National Commission of Persons with Disabilities in Nigeria decided to use our standards manual as an interim tool and as a starting point to develop a more comprehensive set of national standards. We worked very closely with them over the course of several months, and we hope to see the new national accessibility standards published soon.

We also advocate for disability rights globally through our Equal World campaign. Over the past decade, our campaign supporters have helped achieve the inclusion of disability in the Global Sustainable Development Goals, the publication of disability strategies by the World Bank, the United Nations and the UK government, and the milestone of gender equality on the UN disability committee. We are now campaigning to ensure the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and other international and national government commitments are disability inclusive, as well as calling for the ratification of the African Disability Protocol (5).

In addition, we have just launched our inclusive communications accessibility pack, which offers guidelines for creating accessible communications that are easy to understand, user-friendly, and available in many formats (6). Frankly, there’s so much we’re working on, it’s hard to cover it all in a single article! You can find out more about our work at the Sightsavers website

A Shared Responsibility

Promoting access to health equity for people with disabilities is a shared responsibility – and we all have a role to play. Whether you are managing a project, running a clinic, leading a team, or you are at the beginning of your professional journey, there is always something you can do to make health services more inclusive and accessible. Dedicate a portion of your budget to inclusion, collaborate with your local OPDs, build capacity of your staff, improve the accessibility of local health facilities, make communication materials more inclusive. Together, we can ensure health for all becomes a reality, with no one left behind.

References

- Zero Project, “Toolkit and training to make health facilities in low-income countries more accessible.” (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3MN6L5C

- Sightsavers, “Lessons from the Boresha Macho eye health programme in Tanzania.” (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/3C4lpkf

- Inclusive Futures, “Improving access to family planning for people with disabilities.” (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/43i7J0L

- Inclusive Futures, “Our work on inclusive early childhood development and education in Kenya.” (2022). Available at: https://bit.ly/3oETiVt

- Sightsavers, “Ratify the African Disability Protocol.” (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/42io9VB

- Sightsavers, “How to make your work inclusive.” (2023). Available at: https://bit.ly/45DT0Pp