- How satisfied are you with our job?

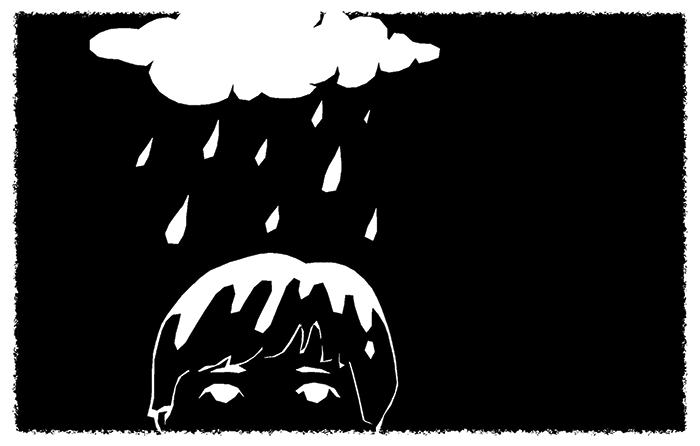

- Increasing paperwork and corporatization, the loss of autonomy, and the need to keep up with new technologies and remain competitive are all issues that can leave ophthalmologists with less time to spend with their patients

- Ophthalmologists must adapt tosurvive – better preparing residents and providing support for practicing doctors could help balance their priorities, and boost job satisfaction too

- Ophthalmology is a hugely rewarding profession, and looking at ways to prevent frustration and burnout benefits both doctors and their patients

If you could return to the beginning of your medical training, would you still choose ophthalmology? Going back even further, would you still choose medicine? To many ophthalmologists, the answer is obvious – but is every ophthalmologist happy with the path they’ve chosen? In his work as a medical ethicist, John Banja has been lucky to get the opportunity to gain an insider’s look into the world of some anterior segment surgeons, and here he shares his observations on an important but sometimes overlooked topic amongst ophthalmologists: job satisfaction.

John Banja is a Professor at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, a medical ethicist at the Center for Ethics, Emory University, Georgia, USA, and the editor of AJOB Neuroscience.