The period between 1991 and 2001 was a very good time for the annual Formula 1 Brazilian Grand Prix in São Paulo. It was also a period when I was extremely fortunate to serve as the circuit ophthalmologist, supervising eye care of the drivers, also known as pilots, and their crews. I was invited by the organizers to join the medical crew, and when they were happy with the job I did in the first couple of years, I was invited back again for the following several years. I was the first ophthalmologist to bring equipment from their office, bringing with me my slit lamp, an indirect and direct ophthalmoscope, a Snellen chart, and other equipment to support me – an approach that was very much appreciated by the organizers as they felt I was able to perform a better level of service.

My main role was to be on hand to help with ocular injuries. Fortunately, there were no major injuries during my tenure, but I was well prepared for all eventualities. We had larger surgical teams on standby in case their support was needed. What I mostly attended to were minor injuries sustained by the Formula 1 mechanics. There was one instance when I had to help an American pilot, Michael Andretti, who drove for McLaren. He suffered a major crash right where by the start of the track and I was really close by and attended to his injuries, not only as an ophthalmologist, but also as an emergency physician.

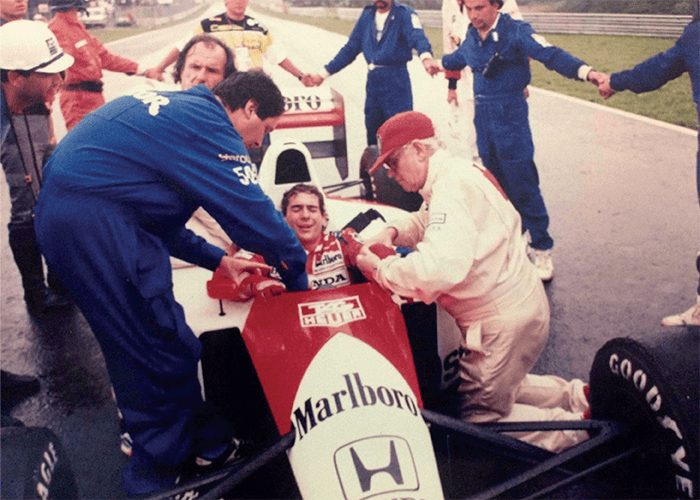

Ayrton Senna, from the archive of Milton Yogi.

Ayrton Senna, from the archive of Milton Yogi.

Dream come true

I have been a big Formula 1 fan since I was seven years old. In the 1970s, when I was growing up, Brazil had an amazing driver named Emerson Fittipaldi (he won the Formula 1 World Championship and the Indianapolis 500 twice, and the CART championship once), and watching his career got me into following the sport closely.

When I started my role as the Grand Prix circuit ophthalmologist, I proceeded to build relationships with crews on different teams so I could learn more about Formula 1’s inner workings. I got access into their boxes and found out a lot about their work. That meant so much to me, as I’d always wanted to see the parts of the Grand Prix that are hidden from the general public.

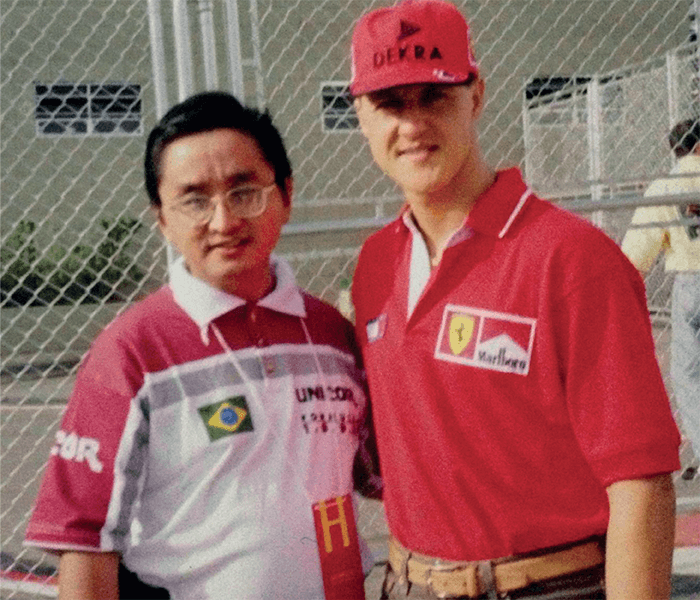

Milton Yogi with Michael Schumacher at the Brazilian F1 Grand Prix.

Milton Yogi with Michael Schumacher at the Brazilian F1 Grand Prix.

I also got to spend time with pilots, including such legends as Ayrton Senna and Nelson Piquet. They would invite me into their boxes and everyone always treated me with utmost respect. Not all team doctors were as big fans of Formula 1 as I was, so drivers and crews really related to me.

Senna had a dream of winning the Grand Prix in Brazil, his home country. It always seemed to escape him, and in 1991, as he was in the lead, in mild rain, his gearbox broke down. He took his final laps of the race with one gear, without anyone knowing that at the time. It was something that had never seemed possible. As Senna crossed the line at winning speed, I was lucky to be in the pit wall. It was truly a dream come true for me and I will never forget that. I was also there for the champagne shower at the podium!

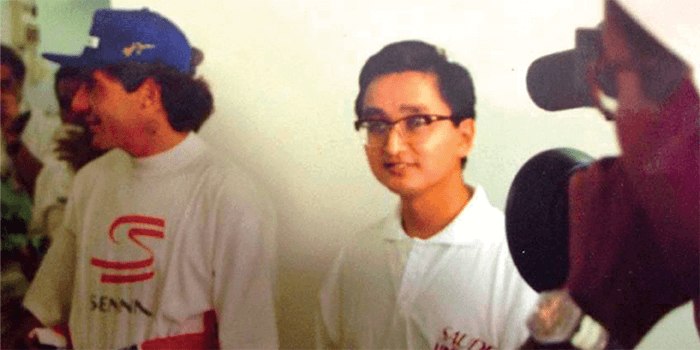

Milton Yogi with Ayrton Senna.

Milton Yogi with Ayrton Senna.

Formula 1 vision

Apart from perfect visual acuity, racing drivers have extraordinary reflexes. They react very quickly while driving, but also when accidents happen. The position in a racing car cockpit tube – a tiny, confined space – is almost horizontal, and when I tried it myself, I couldn’t understand how drivers were able to see anything. They have a very unusual perception of things ahead of them and around them. They train their vision and reflexes all the time. Each successful driver has their own personal trainer who not only looks after their overall physical shape, but also their reflexes. I had the opportunity to check the vision of one driver, Thierry Boutsen, who at the time raced with Williams. He needed a check up to renew his super licence, and I was asked to conduct his tests.

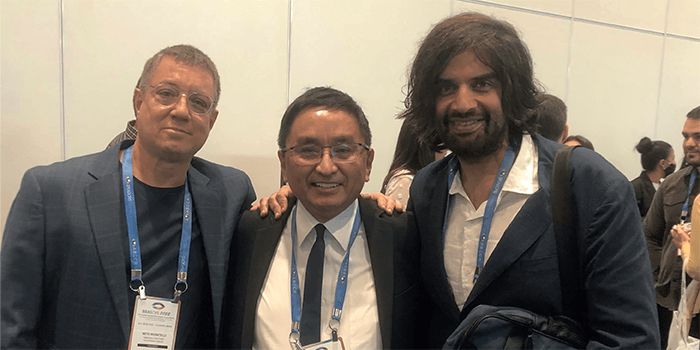

Milton Yogi working at the Brazilian Formula 1 Grand Prix. Photographs are from his personal archive.

Milton Yogi working at the Brazilian Formula 1 Grand Prix. Photographs are from his personal archive.

Many times, Brazil has been announced as the country best supporting emergency healthcare in Formula 1 events, and having participated in this sport at such a high level makes me very proud. I decided to do things my way: bring my equipment and arrange the space in the best way I could to provide support (working on it for up to a week ahead of each event) and I’m extremely happy I did that, as it helped me provide the best possible care for pilots and their crews, which then came to be regarded as best practice.

Hero and Teaser Credit: People images sourced from Shutterstock.com

References

- MF Land, BW Tatler, “Steering with the head. The visual strategy of a racing driver,” Curr Biol, 11, 1215 (2001). PMID: 11516955.